Book Title: Syntactic Gleanings From Bhartharis Trikandi Author(s): Ashok Aklujkar Publisher: Ashok Aklujkar View full book textPage 3

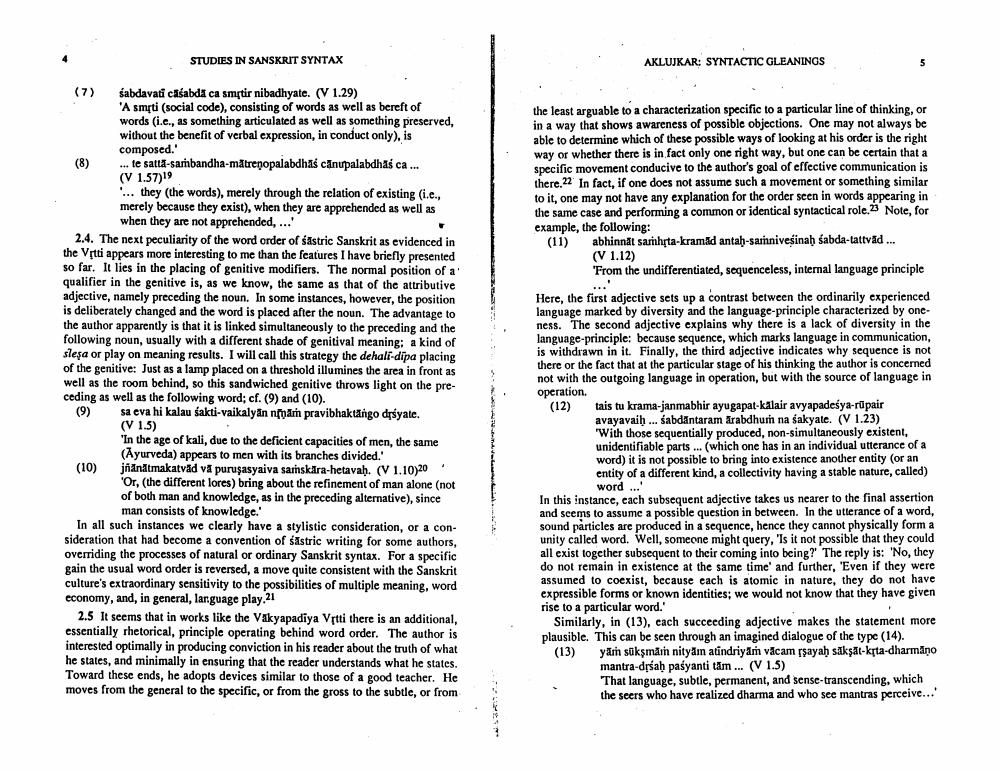

________________ STUDIES IN SANSKRIT SYNTAX AKLUJKAR: SYNTACTIC GLEANINGS (8) the least arguable to a characterization specific to a particular line of thinking, or in a way that shows awareness of possible objections. One may not always be able to determine which of these possible ways of looking at his order is the right way or whether there is in fact only one right way, but one can be certain that a specific movement conducive to the author's goal of effective communication is there.22 In fact, if one does not assume such a movement or something similar to it, one may not have any explanation for the order seen in words appearing in the same case and performing a common or identical syntactical role.23 Note, for example, the following: (11) abhinnat sarnhta-kramad antah-saminivesinah Sabda-lattvad... (V 1.12) "From the undifferentiated, sequenceless, internal language principle (7) sabdavati caśabdä сa smptir nibadhyate. (V 1.29) nyti (social code), consisting of words as well as bereft of words (i.c., as something articulated as well as something preserved, without the benefit of verbal expression, in conduct only), is composed.' ... te satta-sambandha-matrenopalabdhas canupalabdhas ca... (V 1.57)19 ... they (the words), merely through the relation of existing (i.e.. merely because they exist), when they are apprehended as well as when they are not apprehended, ...' 2.4. The next peculiarity of the word order of śastric Sanskrit as evidenced in the Vitti appears more interesting to me than the features I have bricly presented so far. It lies in the placing of genitive modifiers. The normal position of a' qualifier in the genitive is, as we know, the same as that of the attributive adjective, namely preceding the noun. In some instances, however, the position is deliberately changed and the word is placed after the noun. The advantage to the author apparently is that it is linked simultaneously to the preceding and the following noun, usually with a different shade of genitival meaning: a kind of play on meaning results. I will call this strategy the dehali-dipa placing of the genitive: Just as a lamp placed on a threshold illumines the area in front as well as the room behind, so this sandwiched genitive throws light on the preceding as well as the following word; cf. (9) and (10). (9) sa eva hi kalau sakti-vaikalyan nmam pravibhaktango drøyate. (V 1.5) 'In the age of kali, due to the deficient capacities of men, the same (Ayurveda) appears to men with its branches divided.' jñanatmakatvad va purusasyaiva sarskara-hetavah. (V 1.10320 'Or, (the different lores) bring about the refinement of man alone (not of both man and knowledge, as in the preceding alternative), since man consists of knowledge.' In all such instances we clearly have a stylistic consideration, or a consideration that had become a convention of Sastric writing for some authors, overriding the processes of natural or ordinary Sanskrit syntax. For a specific gain the usual word order is reversed, a move quite consistent with the Sanskrit culture's extraordinary sensitivity to the possibilities of multiple meaning, word economy, and, in general, larguage play.21 2.5 It seems that in works like the Vakyapadiya Vrtti there is an additional, essentially rhetorical, principle operating behind word order. The author is interested optimally in producing conviction in his reader about the truth of what he states, and minimally in ensuring that the reader understands what he states. Toward these ends, he adopts devices similar to those of a good teacher. He moves from the general to the specific, or from the gross to the subtle, or from (10) Here, the first adjective sets up a contrast between the ordinarily experienced language marked by diversity and the language-principle characterized by oneness. The second adjective explains why the language-principle: because sequence, which marks language in communication, is withdrawn in it. Finally, the third adjective indicates why sequence is not there or the fact that at the particular stage of his thinking the author is concerned not with the outgoing language in operation, but with the source of language in operation. (12) tais tu krama-janmabhir ayugapat-kalair avyapadesya-rupair avayavaiḥ ... sabdantaram arabdhum na sakyate. (V 1.23) "With those sequentially produced, non-simultaneously existent, unidentifiable parts ... (which one has in an individual utterance of a word) it is not possible to bring into existence another entity (or an entity of a different kind, a collectivity having a stable nature, called) word ... In this instance, cach subsequent adjective takes us nearer to the final assertion and seems to assume a possible question in between. In the utterance of a word, sound particles are produced in a sequence, hence they cannot physically form a unity called word. Well, someone might query, 'Is it not possible that they could all exist together subsequent to their coming into being?' The reply is: 'No, they do not remain in existence at the same time and further, 'Even if they were assumed to coexist, because each is atomic in nature, they do not have expressible forms or known identities; we would not know that they have given rise to a particular word. Similarly, in (13), cach succeeding adjective makes the statement more plausible. This can be seen through an imagined dialogue of the type (14). (13) yarn söksman nityam atindriyam vācam sayah saksal-krta-dharmino mantra-dršah paśyanti tam... (V 1.5) That language, subtle, permanent, and sense-transcending, which the seers who have realized dharma and who see mantras perceive...'Page Navigation

1 2 3 4 5 6