Book Title: Sectional Studies In Jainology II Author(s): Klaus Bruhn Publisher: Klaus Bruhn View full book textPage 9

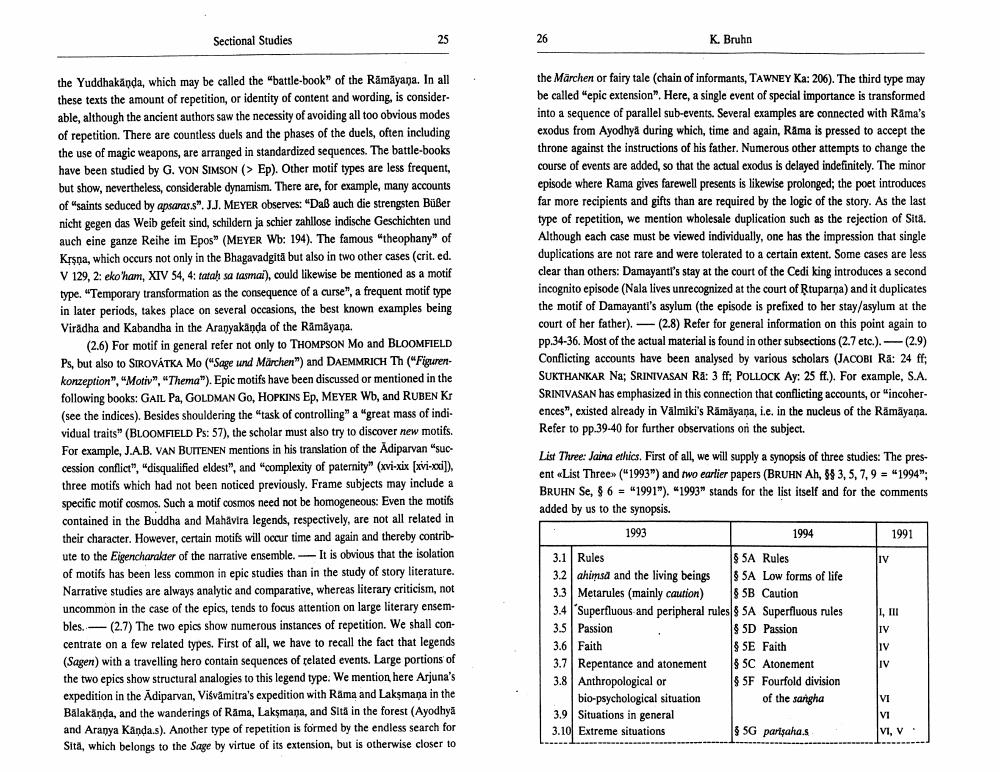

________________ Sectional Studies K. Bruhn . the Yuddhakanda, which may be called the "battle-book" of the Ramayana. In all these texts the amount of repetition, or identity of content and wording, is consider able, although the ancient authors saw the necessity of avoiding all too obvious modes of repetition. There are countless duels and the phases of the duels, often including the use of magic weapons, are arranged in standardized sequences. The battle-books have been studied by G. VON SIMSON (> Ep). Other motif types are less frequent, but show, nevertheless, considerable dynamism. There are, for example, many accounts of "saints seduced by apsarass". JJ. MEYER observes: "Daß auch die strengsten Büßer nicht gegen das Weib gefeit sind, schildern ja schier zahllose indische Geschichten und auch eine ganze Reihe im Epos" (MEYER Wb: 194). The famous "theophany of Krsoa, which occurs not only in the Bhagavadgita but also in two other cases (crit. ed. V 129, 2: eko'ham, XIV 54, 4: tatah sa tamai), could likewise be mentioned as a motif type. "Temporary transformation as the consequence of a curse", a frequent motif type in later periods, takes place on several occasions, the best known examples being Viradha and Kabandha in the Aranyakanda of the Ramayana. (2.6) For motif in general refer not only to THOMPSON Mo and BLOOMFIELD Ps, but also to SIROVÁTKA Mo ("Sage und Märchen") and DAEMMRICH Th ("Figurenkonzeption", "Motiv", "Thema"). Epic motifs have been discussed or mentioned in the following books: GAIL Pa, GOLDMAN Go, HOPKINS Ep. MEYER Wb, and RUBEN K (see the indices). Besides shouldering the task of controlling" a "great mass of individual traits" (BLOOMFIELD Ps: 57), the scholar must also try to discover new motifs. For example, J.A.B. VAN BUITENEN mentions in his translation of the Adiparvan "suc cession conflict", "disqualified eldest", and "complexity of paternity" (xvi-xix (xvi-xodi]). three motifs which had not been noticed previously. Frame subjects may include a specific motif cosmos. Such a motif cosmos need not be homogeneous: Even the motifs contained in the Buddha and Mahavira legends, respectively, are not all related in their character. However, certain motifs will occur time and again and thereby contribute to the Eigencharakter of the narrative ensemble. It is obvious that the isolation of motifs has been less common in epic studies than in the study of story literature. Narrative studies are always analytic and comparative, whereas literary criticism, not uncommon in the case of the epics, tends to focus attention on large literary ensembles. — (2.7) The two epics show numerous instances of repetition. We shall concentrate on a few related types. First of all, we have to recall the fact that legends (Sagent) with a travelling hero contain sequences of related events. Large portions of the two epics show structural analogies to this legend type. We mention here Arjuna's expedition in the Adiparvan, Visvāmitra's expedition with Rama and Laksmana in the Balakanda, and the wanderings of Rama, Laksmana, and Sita in the forest (Ayodhya and Aranya Kanda.s). Another type of repetition is formed by the endless search for Sita, which belongs to the Sage by virtue of its extension, but is otherwise closer to the Märchen or fairy tale (chain of informants, TAWNEY Ka: 206). The third type may be called "epic extension". Here, a single event of special importance is transformed into a sequence of parallel sub-events. Several examples are connected with Rama's exodus from Ayodhya during which, time and again, Rama is pressed to accept the throne against the instructions of his father. Numerous other attempts to change the course of events are added, so that the actual exodus is delayed indefinitely. The minor episode where Rama gives farewell presents is likewise prolonged; the poet introduces far more recipients and gifts than are required by the logic of the story. As the last type of repetition, we mention wholesale duplication such as the rejection of Sita. Although each case must be viewed individually, one has the impression that single duplications are not rare and were tolerated to a certain extent. Some cases are less clear than others: Damayanti's stay at the court of the Cedi king introduces a second incognito episode (Nala lives unrecognized at the court of Rtuparna) and it duplicates the motif of Damayanti's asylum (the episode is prefixed to her stay/asylum at the court of her father). — (2.8) Refer for general information on this point again to pp. 34-36. Most of the actual material is found in other subsections (2.7 etc.). — (2.9) Conflicting accounts have been analysed by various scholars (JACOBI Rā: 24 ff; SUKTHANKAR Na; SRINIVASAN Ra: 3 ff; POLLOCK Ay: 25 ff.). For example, S.A. SRINIVASAN has emphasized in this connection that conflicting accounts, or "incoherences", existed already in Valmiki's Rāmāyana, i.e. in the nucleus of the Rāmāyana. Refer to pp.39-40 for further observations on the subject. List Three: Jaina ethics. First of all, we will supply a synopsis of three studies: The present List Three ("1993") and two earlier papers (BRUHN Ah, 94 3,5,7,9 = "1994", BRUHN Se, 86 - "1991"). "1993" stands for the list itself and for the comments added by us to the synopsis. 1993 1994 1991 3.1 Rules $ SA Rules 3.2 | ahimsa and the living beings 55A Low forms of life 3.3 Metarules (mainly caution) 95B Caution 3.4 | Superfluous and peripheral rules 8 SA Superfluous rules 3.5 Passion $SD Passion 3.6 Faith $ SE Faith 3.7 Repentance and atonement $ 5C Atonement 3.8 Anthropological or 85F Fourfold division bio-psychological situation of the sangha 3.9 Situations in general 3.10 Extreme situations $ SG parisaha.sPage Navigation

1 ... 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25