Book Title: Paninis View Of Meaning And Its Western Counterpart Author(s): Johannes Bronkhorst Publisher: Johannes Bronkhorst View full book textPage 3

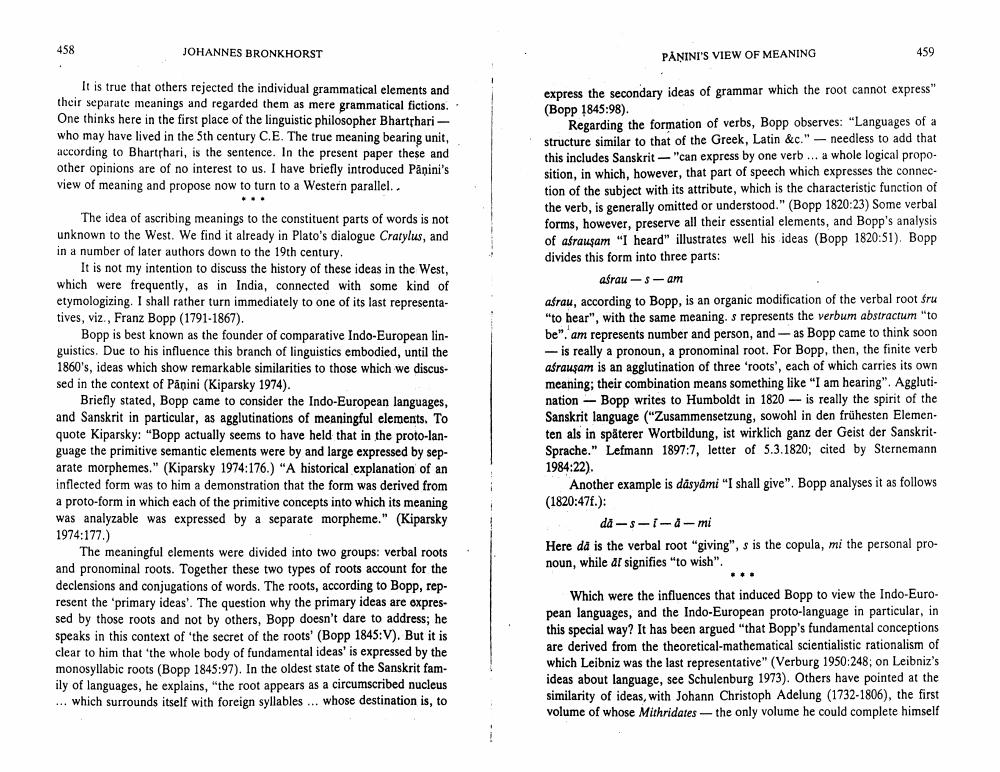

________________ 458 JOHANNES BRONKHORST It is true that others rejected the individual grammatical elements and their separate meanings and regarded them as mere grammatical fictions. One thinks here in the first place of the linguistic philosopher Bhartthariwho may have lived in the 5th century C.E. The true meaning bearing unit, according to Bhartrhari, is the sentence. In the present paper these and other opinions are of no interest to us. I have briefly introduced Panini's view of meaning and propose now to turn to a Western parallel.. The idea of ascribing meanings to the constituent parts of words is not unknown to the West. We find it already in Plato's dialogue Cratylus, and in a number of later authors down to the 19th century. It is not my intention to discuss the history of these ideas in the West, which were frequently, as in India, connected with some kind of etymologizing. I shall rather turn immediately to one of its last representatives, viz., Franz Bopp (1791-1867). Bopp is best known as the founder of comparative Indo-European linguistics. Due to his influence this branch of linguistics embodied, until the 1860's, ideas which show remarkable similarities to those which we discussed in the context of Panini (Kiparsky 1974). Briefly stated, Bopp came to consider the Indo-European languages, and Sanskrit in particular, as agglutinations of meaningful elements. To quote Kiparsky: "Bopp actually seems to have held that in the proto-language the primitive semantic elements were by and large expressed by separate morphemes." (Kiparsky 1974:176.) "A historical explanation of an inflected form was to him a demonstration that the form was derived from a proto-form in which each of the primitive concepts into which its meaning was analyzable was expressed by a separate morpheme." (Kiparsky 1974:177.) The meaningful elements were divided into two groups: verbal roots and pronominal roots. Together these two types of roots account for the declensions and conjugations of words. The roots, according to Bopp, represent the 'primary ideas'. The question why the primary ideas are expressed by those roots and not by others, Bopp doesn't dare to address; he speaks in this context of 'the secret of the roots' (Bopp 1845:V). But it is clear to him that 'the whole body of fundamental ideas' is expressed by the monosyllabic roots (Bopp 1845:97). In the oldest state of the Sanskrit family of languages, he explains, "the root appears as a circumscribed nucleus which surrounds itself with foreign syllables... whose destination is, to PANINI'S VIEW OF MEANING express the secondary ideas of grammar which the root cannot express" (Bopp 1845:98). 459 Regarding the formation of verbs, Bopp observes: "Languages of a structure similar to that of the Greek, Latin &c." needless to add that this includes Sanskrit "can express by one verb... a whole logical proposition, in which, however, that part of speech which expresses the connection of the subject with its attribute, which is the characteristic function of the verb, is generally omitted or understood." (Bopp 1820:23) Some verbal forms, however, preserve all their essential elements, and Bopp's analysis of asrauşam "I heard" illustrates well his ideas (Bopp 1820:51). Bopp divides this form into three parts: - asrau-s-am asrau, according to Bopp, is an organic modification of the verbal root śru "to hear", with the same meaning. s represents the verbum abstractum "to be". am represents number and person, and as Bopp came to think soon - is really a pronoun, a pronominal root. For Bopp, then, the finite verb asrauşam is an agglutination of three 'roots', each of which carries its own meaning; their combination means something like "I am hearing". Aggluti nation - Bopp writes to Humboldt in 1820 is really the spirit of the Sanskrit language ("Zusammensetzung, sowohl in den frühesten Elementen als in späterer Wortbildung, ist wirklich ganz der Geist der SanskritSprache." Lefmann 1897:7, letter of 5.3.1820; cited by Sternemann 1984:22). Another example is däsyämi "I shall give". Bopp analyses it as follows (1820:47f.): dă-s--a-mi Here då is the verbal root "giving", s is the copula, mi the personal pronoun, while al signifies "to wish". Which were the influences that induced Bopp to view the Indo-European languages, and the Indo-European proto-language in particular, in this special way? It has been argued "that Bopp's fundamental conceptions are derived from the theoretical-mathematical scientialistic rationalism of which Leibniz was the last representative" (Verburg 1950:248; on Leibniz's ideas about language, see Schulenburg 1973). Others have pointed at the similarity of ideas, with Johann Christoph Adelung (1732-1806), the first volume of whose Mithridates the only volume he could complete himselfPage Navigation

1 2 3 4 5 6