Book Title: Paninis View Of Meaning And Its Western Counterpart Author(s): Johannes Bronkhorst Publisher: Johannes Bronkhorst View full book textPage 2

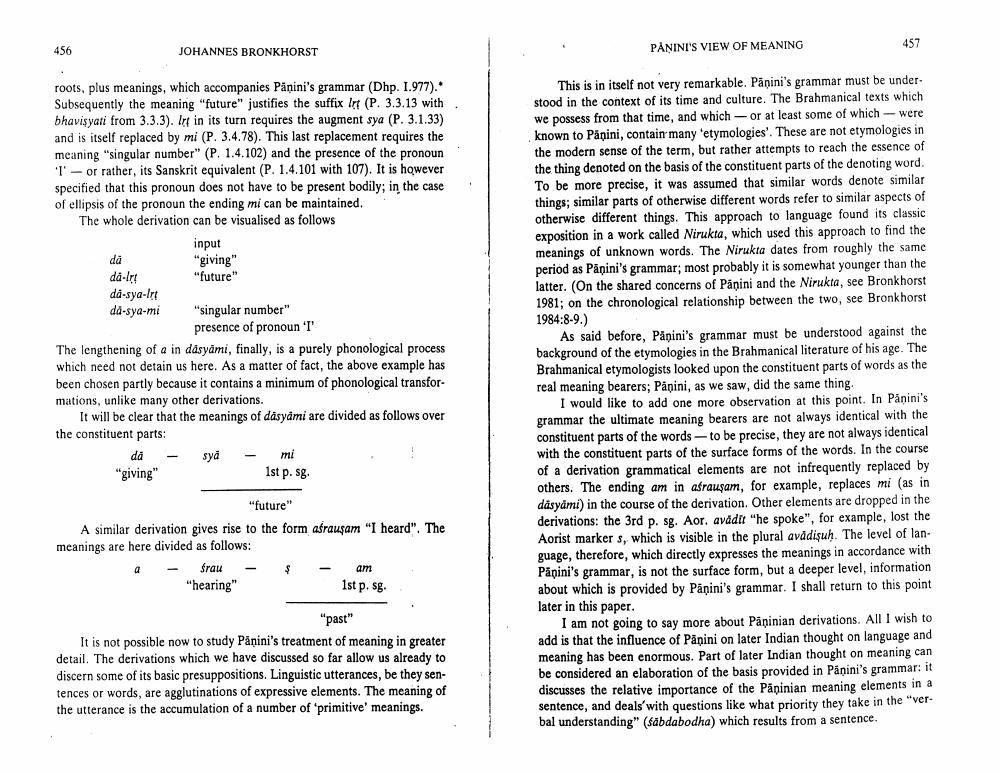

________________ 456 JOHANNES BRONKHORST PANINI'S VIEW OF MEANING 457 roots, plus meanings, which accompanies Panini's grammar (Dhp. 1.977). Subsequently the meaning "future" justifies the suffix lrt (P. 3.3.13 with bhavisyati from 3.3.3). Irt in its turn requires the augment sya (P. 3.1.33) and is itself replaced by mi (P. 3.4.78). This last replacement requires the meaning "singular number" (P. 1.4.102) and the presence of the pronoun 'T' - or rather, its Sanskrit equivalent (P. 1.4.101 with 107). It is however specified that this pronoun does not have to be present bodily; in the case of ellipsis of the pronoun the ending mi can be maintained. The whole derivation can be visualised as follows input da "giving" dá-lry "future" da-sya-Irt dd-sya-mi "singular number" presence of pronoun T The lengthening of a in dasyāmi, finally, is a purely phonological process which need not detain us here. As a matter of fact, the above example has been chosen partly because it contains a minimum of phonological transfor. mations, unlike many other derivations. It will be clear that the meanings of dasyami are divided as follows over the constituent parts: då - sya - mi "giving" 1st p. sg. This is in itself not very remarkable. Panini's grammar must be under stood in the context of its time and culture. The Brahmanical texts which we possess from that time, and which or at least some of which were known to Panini, contain many 'etymologies'. These are not etymologies in the modern sense of the term, but rather attempts to reach the essence of the thing denoted on the basis of the constituent parts of the denoting word. To be more precise, it was assumed that similar words denote similar things; similar parts of otherwise different words refer to similar aspects of otherwise different things. This approach to language found its classic exposition in a work called Nirukta, which used this approach to find the meanings of unknown words. The Nirukta dates from roughly the same period as Panini's grammar; most probably it is somewhat younger than the latter. (On the shared concerns of Panini and the Nirukta, see Bronkhorst 1981; on the chronological relationship between the two, see Bronkhorst 1984:8-9.) As said before, Pånini's grammar must be understood against the background of the etymologies in the Brahmanical literature of his age. The Brahmanical etymologists looked upon the constituent parts of words as the real meaning bearers; Pāņini, as we saw, did the same thing I would like to add one more observation at this point. In Panini's grammar the ultimate meaning bearers are not always identical with the constituent parts of the words to be precise, they are not always identical with the constituent parts of the surface forms of the words. In the course of a derivation grammatical elements are not infrequently replaced by others. The ending am in afrausam, for example, replaces mi (as in dåsydml) in the course of the derivation. Other elements are dropped in the derivations: the 3rd p. sg. Aor, avddit "he spoke", for example, lost the Aorist markers, which is visible in the plural avadişuh. The level of language, therefore, which directly expresses the meanings in accordance with Panini's grammar, is not the surface form, but a deeper level, information about which is provided by Påņini's grammar. I shall return to this point later in this paper. I am not going to say more about Påņinian derivations. All I wish to add is that the influence of Pånini on later Indian thought on language and meaning has been enormous. Part of later Indian thought on meaning can be considered an elaboration of the basis provided in Pånini's grammar: it discusses the relative importance of the Paninian meaning elements in a sentence, and deals with questions like what priority they take in the "ver. bal understanding" (sabdabodha) which results from a sentence. "future" A similar derivation gives rise to the form afrausam "I heard". The meanings are here divided as follows: a - frau - $ - am "hearing" 1st p. sg. "past" It is not possible now to study Panini's treatment of meaning in greater detail. The derivations which we have discussed so far allow us already to discern some of its basic presuppositions. Linguistic utterances, be they sentences or words, are agglutinations of expressive elements. The meaning of the utterance is the accumulation of a number of 'primitive' meanings.Page Navigation

1 2 3 4 5 6