Book Title: Is Inexplicability Otherwise Otherwise Inexplicable Author(s): Piotr Balcerowicz Publisher: Piotr Balcerowicz View full book textPage 9

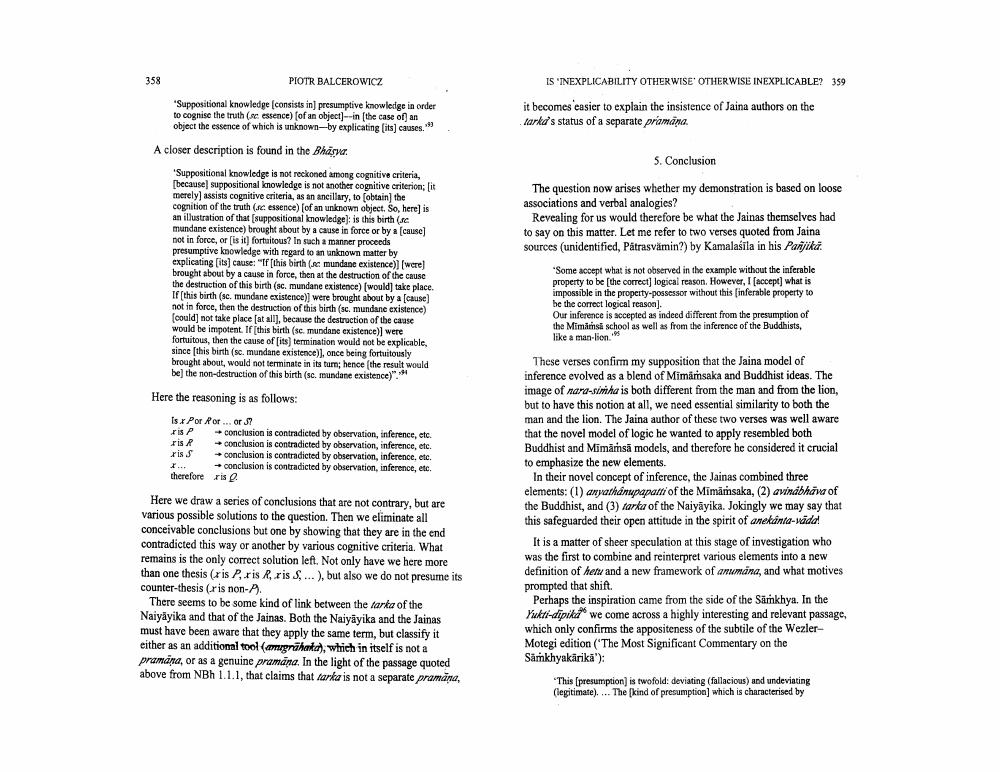

________________ 358 PIOTR BALCEROWICZ "Suppositional knowledge [consists in] presumptive knowledge in order to cognise the truth (se essence) [of an object]--in [the case of] an object the essence of which is unknown-by explicating [its] causes."" A closer description is found in the Bharya Suppositional knowledge is not reckoned among cognitive criteria, [because] suppositional knowledge is not another cognitive criterion; [it merely) assists cognitive criteria, as an ancillary, to [obtain] the cognition of the truth (sc: essence) [of an unknown object. So, here] is an illustration of that [suppositional knowledge]: is this birth (re mundane existence) brought about by a cause in force or by a [cause] not in force, or [is it] fortuitous? In such a manner proceeds presumptive knowledge with regard to an unknown matter by explicating [its] cause: "If [this birth (ac mundane existence)] [were] brought about by a cause in force, then at the destruction of the cause the destruction of this birth (sc. mundane existence) [would] take place. If [this birth (sc. mundane existence)] were brought about by a [cause) not in force, then the destruction of this birth (sc. mundane existence) [could] not take place [at all], because the destruction of the cause would be impotent. If [this birth (sc. mundane existence)] were fortuitous, then the cause of [its] termination would not be explicable, since [this birth (sc. mundane existence)], once being fortuitously brought about, would not terminate in its turn; hence (the result would be] the non-destruction of this birth (sc. mundane existence)"."" Here the reasoning is as follows: Is x Por Ror... or 5? xis P ris R ris S conclusion is contradicted by observation, inference, etc. →conclusion is contradicted by observation, inference, etc. →conclusion is contradicted by observation, inference, etc. → conclusion is contradicted by observation, inference, etc. therefore ris Q. X... Here we draw a series of conclusions that are not contrary, but are various possible solutions to the question. Then we eliminate all conceivable conclusions but one by showing that they are in the end contradicted this way or another by various cognitive criteria. What remains is the only correct solution left. Not only have we here more than one thesis (ris Pris R, ris S,...), but also we do not presume its counter-thesis (ris non-P). There seems to be some kind of link between the tarka of the Naiyayika and that of the Jainas. Both the Naiyayika and the Jainas must have been aware that they apply the same term, but classify it either as an additional tool (anugrahata), which in itself is not a pramana, or as a genuine pramana. In the light of the passage quoted above from NBh 1.1.1, that claims that tarka is not a separate pramāņa, IS INEXPLICABILITY OTHERWISE OTHERWISE INEXPLICABLE? 359 it becomes easier to explain the insistence of Jaina authors on the tarka's status of a separate pramana. 5. Conclusion The question now arises whether my demonstration is based on loose associations and verbal analogies? Revealing for us would therefore be what the Jainas themselves had to say on this matter. Let me refer to two verses quoted from Jaina sources (unidentified, Pâtrasvamin?) by Kamalasila in his Panjikā. "Some accept what is not observed in the example without the inferable property to be [the correct] logical reason. However, I [accept] what is impossible in the property-possessor without this [inferable property to be the correct logical reason]. Our inference is accepted as indeed different from the presumption of the Mimämsä school as well as from the inference of the Buddhists, like a man-lion. These verses confirm my supposition that the Jaina model of inference evolved as a blend of Mimämsaka and Buddhist ideas. The image of nara-simha is both different from the man and from the lion, but to have this notion at all, we need essential similarity to both the man and the lion. The Jaina author of these two verses was well aware that the novel model of logic he wanted to apply resembled both Buddhist and Mimämsä models, and therefore he considered it crucial to emphasize the new elements. In their novel concept of inference, the Jainas combined three elements: (1) anyathanupapatti of the Mimämsaka, (2) avindbhāva of the Buddhist, and (3) tarka of the Naiyayika. Jokingly we may say that this safeguarded their open attitude in the spirit of anekanta-vada! It is a matter of sheer speculation at this stage of investigation who was the first to combine and reinterpret various elements into a new definition of her and a new framework of anumana, and what motives prompted that shift. Perhaps the inspiration came from the side of the Samkhya. In the Yukti-dipika we come across a highly interesting and relevant passage, which only confirms the appositeness of the subtile of the WezlerMotegi edition ("The Most Significant Commentary on the Samkhyakärikä'): "This [presumption] is twofold: deviating (fallacious) and undeviating (legitimate).... The [kind of presumption] which is characterised byPage Navigation

1 ... 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20