________________

OCTOBER, 1930 ]

THE VELAR ASPIRATE IN DRAVIDIAN

201

ta

ou

In connection with the change of t to h above, it has been recently postulated that the aspirate is produced from an original Dravidian 8 and that itself is derived from 8. It is true that Tuļu shows the change of initial s to t in certain alternative forms like sanci, tanci, etc. But it would be sheer topsy-turvydom to consider 8 as the original form in the instances given in (b) above, when the corresponding common roots and forms in all the other Dravidian dialects show clearly the initial t. It should also be remembered in this connection that the change of t to is peculiar to Tulu, and that it does not occur in Kannada.

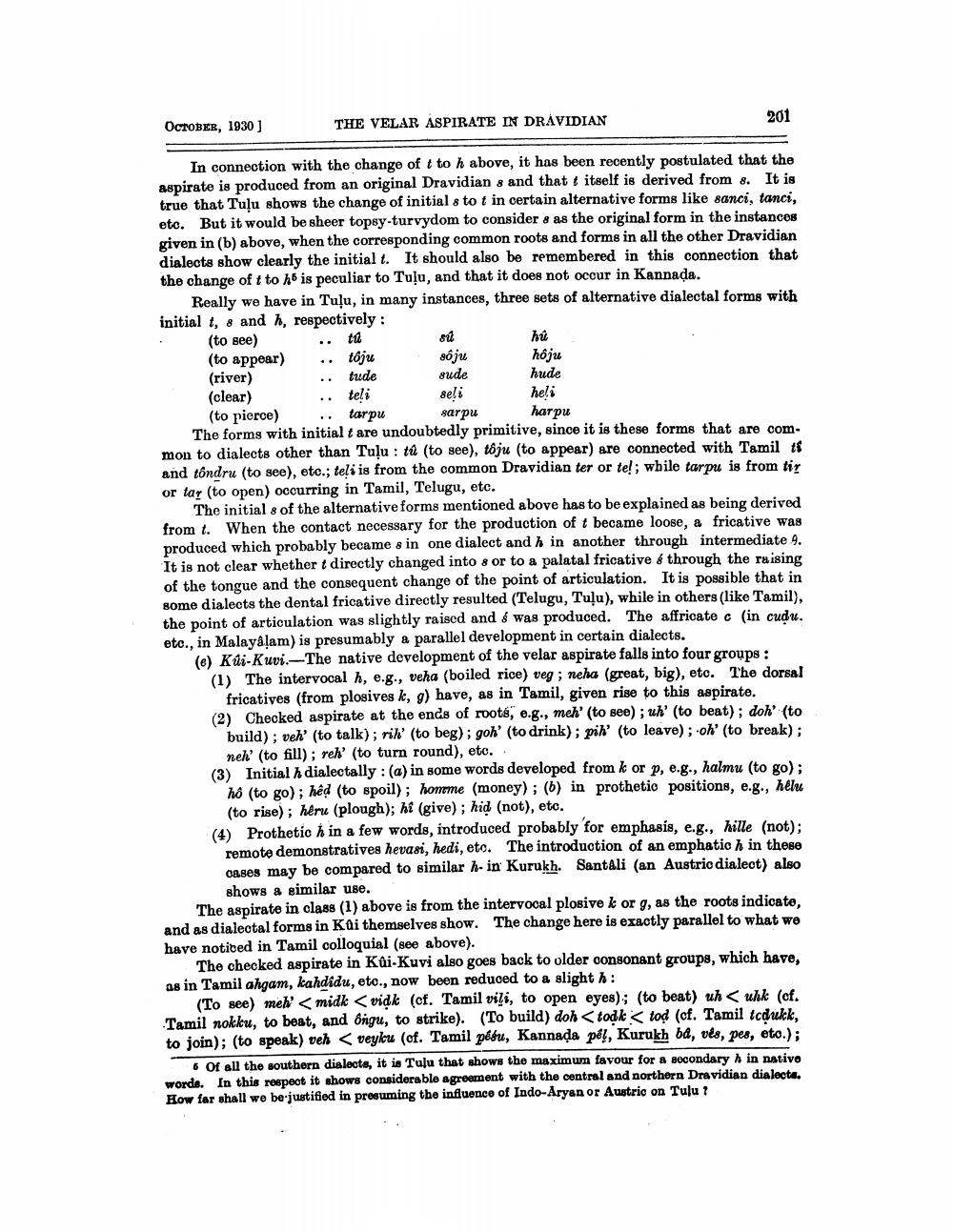

Really we have in Tuļu, in many instances, three sets of alternative dialectal forms with initial t, & and h, respectively : (to see)

hú (to appear) .. tôju

soju

hộju (river)

..tude sude hude (clear) .. teli

seli heli (to pierce) .. tarpu sarpu

harpu The forms with initial t are undoubtedly primitive, since it is these forms that are com mon to dialects other than Tuļu : tú (to see), tôju (to appear) are connected with Tamil ti and tôndru (to see), etc.; teli is from the common Dravidian ter or te!; while tarpu is from tir or tar (to open) occurring in Tamil, Telugu, etc.

The initial of the alternative forms mentioned above has to be explained as being derived from t. When the contact necessary for the production of t became loose, a fricative was produced which probably became s in one dialect and h in another through intermediate 4. It is not clear whether t directly changed into 8 or to a palatal fricative & through the raising of the tongue and the consequent change of the point of articulation. It is possible that in some dialects the dental fricative directly resulted (Telugu, Tuļu), while in others (like Tamil). the point of articulation was slightly raised and ó was produced. The affricate c (in cudu. etc., in Malayalam) is presumably a parallel development in certain dialects.

(6) Kúi-Kuvi.-The native development of the velar aspirate falls into four groups : (1) The intervocal h, e.g., veha (boiled rice) veg; neha (great, big), etc. The dorsal

fricatives (from plosives k, g) have, as in Tamil, given rise to this aspirate. (2) Checked aspirate at the ends of roots, e.g., meh' (to see); wh' (to beat): doh' (to

build); veh' (to talk); rih' (to beg); goh' (to drink); pik' (to leave); oh' (to break);

neh' (to fill); reh' (to turn round), eto. (3) Initial h dialectally : (a) in some words developed from k or p, e.g., halmu (to go);

hô (to go); hêd (to spoil); honome (money); (b) in prothetio positions, e.g., hélu

(to rise); héru (plough); hî (give); hid (not), etc. (4) Prothetic h in a few words, introduced probably for emphasis, e.g., Wille (not):

remoto demonstratives hevasi, hedi, etc. The introduction of an emphatio h in these cases may be compared to similar h-in Kurukh. Santali (an Austrio dialect) also

shows a similar use. The aspirate in class (1) above is from the intervocal plosive k or g, as the roots indicate, and as dialectal forms in Kui themselves show. The change here is exactly parallel to what we have notided in Tamil colloquial (see above).

The checked aspirate in Kai-Kuvi also goes back to older consonant groups, which have, as in Tamil angam, kahdídu, etc., now been reduced to a slight h:

(To see) meh < midk <vidk (of. Tamil vili, to open eyes); (to beat) uh uhk (cf. Tamil nokku, to beat, and ongu, to strike). (To build) doh < todk < top (cf. Tamil tcdukk, to join); (to speak) veh veylu (cf. Tamil pesu, Kannada pel, Kurukh ba, vés, pes, eto.);

Of all the southern dialecte, it is Tulu that shows the maximum favour for a socondary , in nativo worde. In this respect it shows considerable agreement with the central and northern Dravidian dialects. How far shall we be justified in prosuming the influence of Indo-Aryan or Austrio on Tulu?