________________

180

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

(JULY, 1928

Purushavimoksha, which is the subject under treatment. To any one who reads the Karikas beginning with the fifty-sixth and ending with the sixty-second, both with and without Mr.

Tilak's karika between the sixty-first and sixty-second, it will be quite clear how the new kårika introduces a digression and cannot therefore have formed part of the original text.

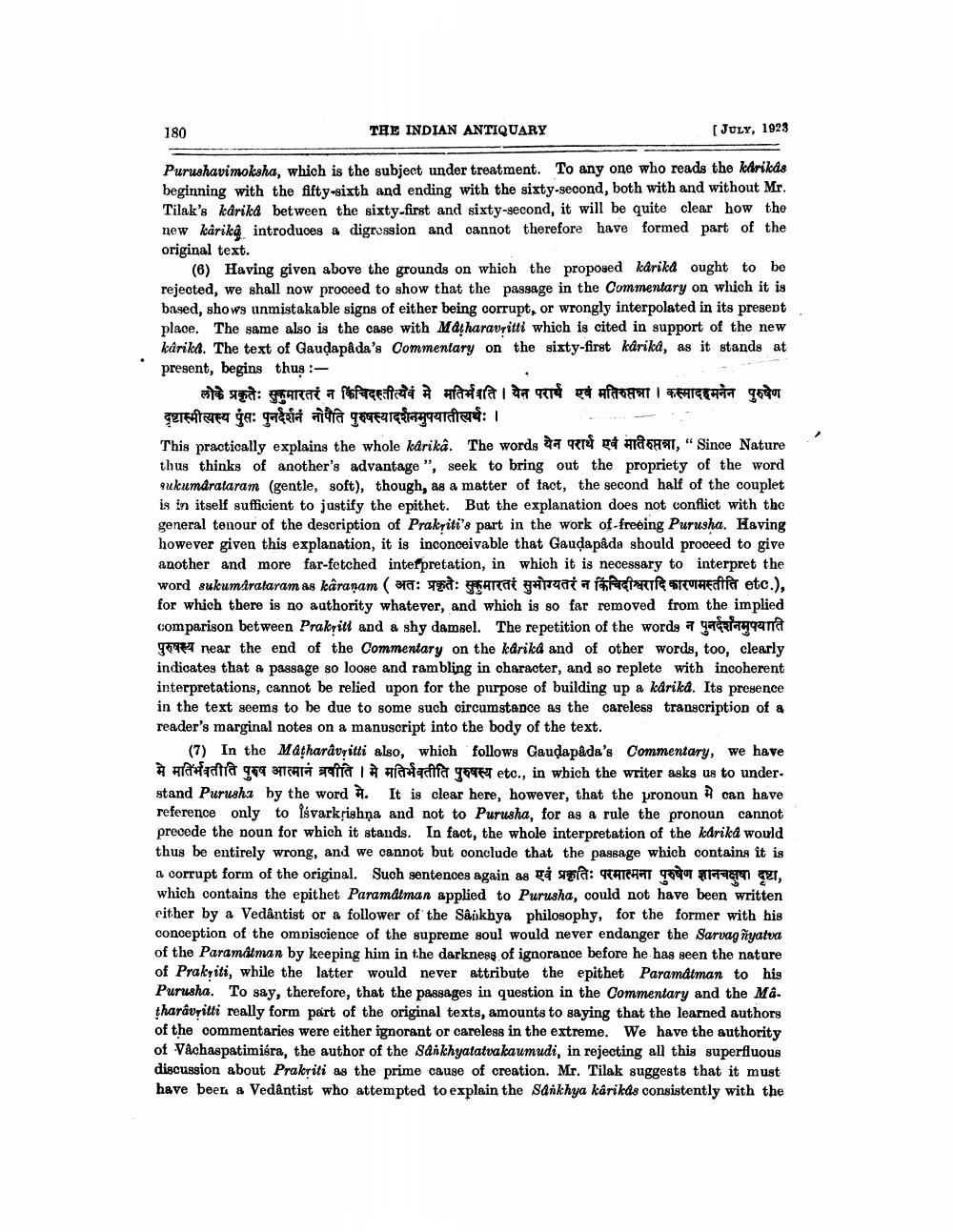

(6) Having given above the grounds on which the proposed karika ought to be rejected, we shall now proceed to show that the passage in the Commentary on which it is based, shows unmistakable signs of either being corrupt, or wrongly interpolated in its present place. The same also is the case with Matharavritti which is cited in support of the new karika. The text of Gaudapâda's Commentary on the sixty-first karika, as it stands at present, begins thus :

लोके प्रकृतेः सुकुमारतरं न किंचिदस्तीत्येवं मे मतिर्भवति । येन परार्य एवं मतिरुप्तन्ना । कस्मादहमनेन पुरुषेण दृष्टास्मीत्यस्य पुंसः पुनदर्शनं नोपैति पुरुषस्यादर्शनमुपयातीत्यर्थः । This practically explains the whole karika. The words and a Habar, "Since Nature thus thinks of another's advantage", seek to bring out the propriety of the word Sukumaralaram (gentle, soft), though, as a matter of fact, the second half of the couplet is in itself sufficient to justify the epithet. But the explanation does not conflict with the general tenour of the description of Prakriti's part in the work of- freeing Purusha. Having however given this explanation, it is inconceivable that Gaudapâda should proceed to give another and more far-fetched interpretation, in which it is necessary to interpret the word sukumdralaram as karanam ( : : Fara gaat afpretatie Theater etc.), for which there is no authority whatever, and which is so far removed from the implied comparison between Prakritt and a shy damsel. The repetition of the words 2 gangara got near the end of the Commentary on the karika and of other words, too, clearly indicates that a passage so loose and rambling in character, and so replete with incoherent interpretations, cannot be relied upon for the purpose of building up a karika. Its presence in the text seems to be due to some such circumstance as the careless transcription of a reader's marginal notes on a manuscript into the body of the text.

(7) In the Matharavritti also, which follows Gaudapâda's Commentary, we have मे मतिर्भवतीति पुरुष आत्मानं ब्रवीति । मे मतिर्भवतीति पुरुषस्य etc., in which the writer asks us to under. stand Purusha by the word . It is clear here, however, that the pronoun H can have reference only to išvarkțishna and not to Purusha, for as a rule the pronoun cannot precede the noun for which it stands. In fact, the whole interpretation of the kdrikd would thus be entirely wrong, and we cannot but conclude that the passage which contains it is a corrupt form of the original. Such sentences again as एवं प्रकृतिः परमात्मना पुरुषेण ज्ञानचक्षुषा दृष्टा, which contains the epithet Paramdtman applied to Purusha, could not have been written either by a Vedântist or a follower of the Sankhya philosophy, for the former with his conception of the omniscience of the supreme soul would never endanger the Sarvag ñyatra of the Paramdiman by keeping him in the darkness of ignorance before he has seen the nature of Prakriti, while the latter would never attribute the epithet Paramatman to his Purusha. To say, therefore, that the passages in question in the Commentary and the Ma. tharavritti really form part of the original texts, amounts to saying that the learned authors of the commentaries were either ignorant or careless in the extreme. We have the authority of Vachaspatimisra, the author of the Sankhyatatvakaumudi, in rejecting all this superfluous discussion about Prakriti as the prime cause of creation. Mr. Tilak suggests that it must have been a Vedantist who attempted to explain the sankhya karikas consistently with the