________________

JULY, 1923)

THE PROBLEM OF THE SANKHYA KARIKAS

179

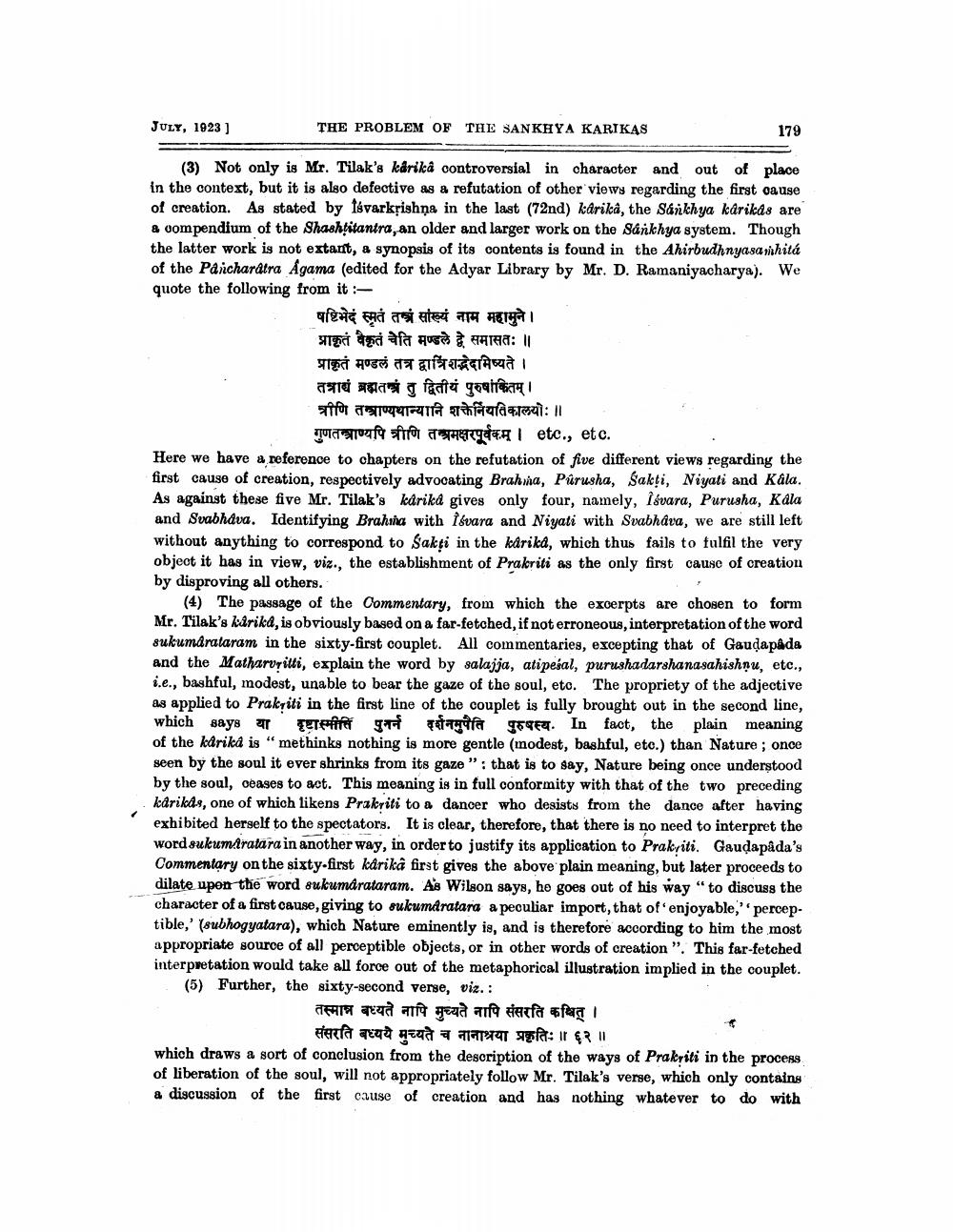

(3) Not only is Mr. Tilak's karikâ controversial in character and out of place in the context, but it is also defective as a refutation of other views regarding the first oa use of creation. As stated by tsvarkrishņa in the last (72nd) kârika, the Sankhya karikás are & compendium of the Shashtitantra, an older and larger work on the Sankhya system. Though the latter work is not extant, a synopsis of its contents is found in the Ahirbudhnyasarhitá of the Pancharatra Agama (edited for the Adyar Library by Mr. D. Ramaniyacharya). We quote the following from it :

षष्टिभेदं स्मृतं तत्रं सांख्यं नाम महामुने। प्राकृतं वैकृतं चेति मण्डले द्वे समासतः ।। प्राकृतं मण्डलं तत्र द्वात्रिंशद्भदमिष्यते । तत्रार्थ ब्रह्मतत्रं तु द्वितीयं पुरुषांकितम् । त्रीणि तत्राण्यथान्यानि शक्तनियतिकालयोः॥ Turcanufa fi

l etc., etc. Here we have a reference to chapters on the refutation of five different views regarding the first cause of creation, respectively advocating Brahna, Púrusha, Sakti, Niyati and Kala. As against these five Mr. Tilak's kårikå gives only four, namely, Isvara, Purusha, Kala and Svabhava. Identifying Brahing with Isvara and Niyati with Svabhava, we are still left without anything to correspond to Sakti in the karika, which thus fails to fulfil the very object it has in view, viz., the establishment of Prakriti as the only first cause of creation by disproving all others.

(4) The passage of the Commentary, from which the excerpts are chosen to form Mr. Tilak's kirikd, is obviously based on a far-fetched, if not erroneous, interpretation of the word sukumarataram in the sixty-first couplet. All commentaries, excepting that of Gaudapáda and the Matharurilli, explain the word by salajja, atipesal, purushadarshanasahishnu, etc., i.e., bashful, modest, unable to bear the gaze of the soul, etc. The propriety of the adjective as applied to Prakriti in the first line of the couplet is fully brought out in the second line, which says या दृष्टास्मीति पुनर्न दर्शनमुपैति पुरुषस्य. In fact, the plain meaning of the karika is "methinks nothing is more gentle (modest, bashful, etc.) than Nature ; once seen by the soul it ever shrinks from its gaze”: that is to say, Nature being once understood by the soul, ceases to act. This meaning is in full conformity with that of the two preceding karikde, one of which likens Prakriti to a dancer who desists from the dance after having exhibited herself to the spectators. It is clear, therefore, that there is no need to interpret the word sukumiratara in another way, in order to justify its application to Prakriti. Gaudapåda's Commentary on the sixty-first karikâ first gives the above plain meaning, but later proceeds to dilate upon the word sukumarataram. As Wilson says, he goes out of his way “to discuss the character of a first cause, giving to sukumdratara a peculiar import, that of enjoyable, peroeptible,' (subhogyatara), which Nature eminently is, and is therefore according to him the most appropriate souroe of all perceptible objects, or in other words of creation". This far-fetched interpretation would take all force out of the metaphorical illustration implied in the couplet. (5) Further, the sixty-second verse, viz. :

तस्मान बध्यते नापि मुच्यते नापि संसरति कश्चित् ।

संसरति बध्यये मुच्यते च नानाश्रया प्रकृतिः ॥ ६२ ॥ which draws a sort of conclusion from the description of the ways of Prakriti in the process of liberation of the soul, will not appropriately follow Mr. Tilak's verse, which only contains a discussion of the first cause of creation and has nothing whatever to do with