________________

Dana Paramita as Ulustrated in Early Indian Buddhist Art

/

237

Agni) and the king who is the main protagonist is named Shivi. The rest of the story is almost the same. The depiction in Gandhara art is close to this version (Fig. 91. The story is chiselled with great command and precision in the Gandhara frieze. On the left. Kapilapingala is seen cutting off the flesh from the thigh of king Shivi. The king, who is seated on his throne, is visibly fatigued and accordingly supported by a lady. However, what is really fascinating about this frieze is that both Shakra and Agni are shown in animal as well as anthropomorphic form. The dove is seated at the foot of the throne and the hawk is shown flving. Shakra and Agni, in anthropomorphic form are seen standing on the extreme right of the frieze. The carving displays an amalgamation of Hellenistic and Indic elements. The human figures have volume and plasticity and can be seen in three-fourth, profile and frontal views. The facial features reveal a significant debt to Hellenistic art, with Iranian style moustache, full eyebrows and heavy faces while the finely pleated dhotis and Shakra's crown are distinctly Indian

At Amravati the Sarvamdada Avadāna is depicted on a rail pillar, in the fluted area between two lotus roundels (Fig. 10). The entire narrative unfolds in the form of three scenes. The first scene one to the left shows the dove seated on king Sarvamdada's lap seeking his protection. Shakra is in the form of the hunter asking for his prey. The scene depicting the king cutting off his own flesh to give to the hunter in place of the dove has been given emphasis in the central flute. The plaintive and the grief-stricken subjects witness the king's great sacrifice in horror. Thus, even in this cloistered space the story is lucidly communicated.

In yet another sculpted frieze of Amaravati we see representations of the same tale [Fig. 11). It portrays a synoptic depiction of both the key scenes of the Avadana. Fig. 12 is a sculptural frieze from Nagarjunakonda (Andhra Pradesh) which shows the king cutting off his own flesh in a poignant manner. The anguish and dismay of the witnesses is clearly palpable even in this depiction.

The Sarvaindada Avadāna is depicted in Cave I of Ajanta (Fig. 13). The two crucial scenes of the dove in the lap of king Sarvamdada and the king standing against the weighing scales can be easily distinguished despite the damaged state of the painting, thus helping identify it.

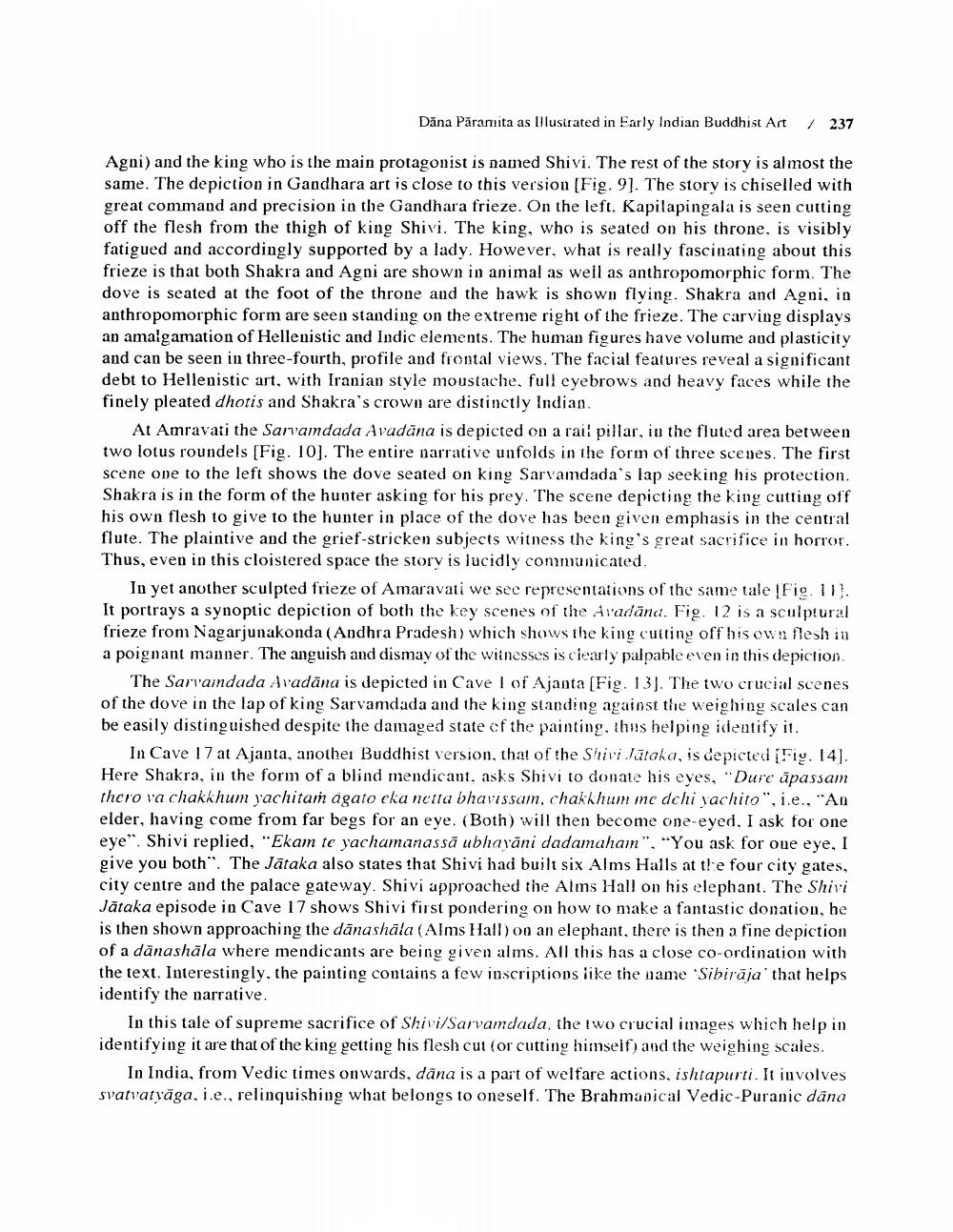

In Cave 17 at Ajanta, another Buddhist version, that of the Shivi Jataka, is depicted (Fig. 14). Here Shakra, in the form of a blind mendicant. asks Shivi to donate his eyes, "Dure ūpassam thero va chakkhum yachitam agato eka netta bhavissam, chakhhum me dchi yachito", i.e., "An elder, having come from far begs for an eye. (Both) will then become one-eyed, I ask for one eye". Shivi replied, "Ekam te yachamanassā ubhayāni dadamaham", "You ask for oue eye, I give you both". The Jätaka also states that Shivi had built six Alms Halls at the four city gates, city centre and the palace gateway. Shivi approached the Alms Hall on his elephant. The Shivi Jātaka episode in Cave 17 shows Shivi first pondering on how to make a fantastic donation, he is then shown approaching the dānashāla (Alms Hall) on an elephant, there is then a fine depiction of a danashāla where mendicants are being given alms. All this has a close co-ordination with the text. Interestingly, the painting contains a few inscriptions like the name 'Sibirāja' that helps identify the narrative.

In this tale of supreme sacrifice of Shivi/Sarvamdada, the two crucial images which help in identifying it are that of the king getting his flesh cut (or cutting himself) and the weighing scales.

In India, from Vedic times onwards, dāna is a part of welfare actions, ishtapurti. It involves svatvatyäga, i.e., relinquishing what belongs to oneself. The Brahmavical Vedic-Puranic dana