Book Title: Sanskrit Pranabhrt Or What Supports what Author(s): A Wezler Publisher: A Wezler View full book textPage 3

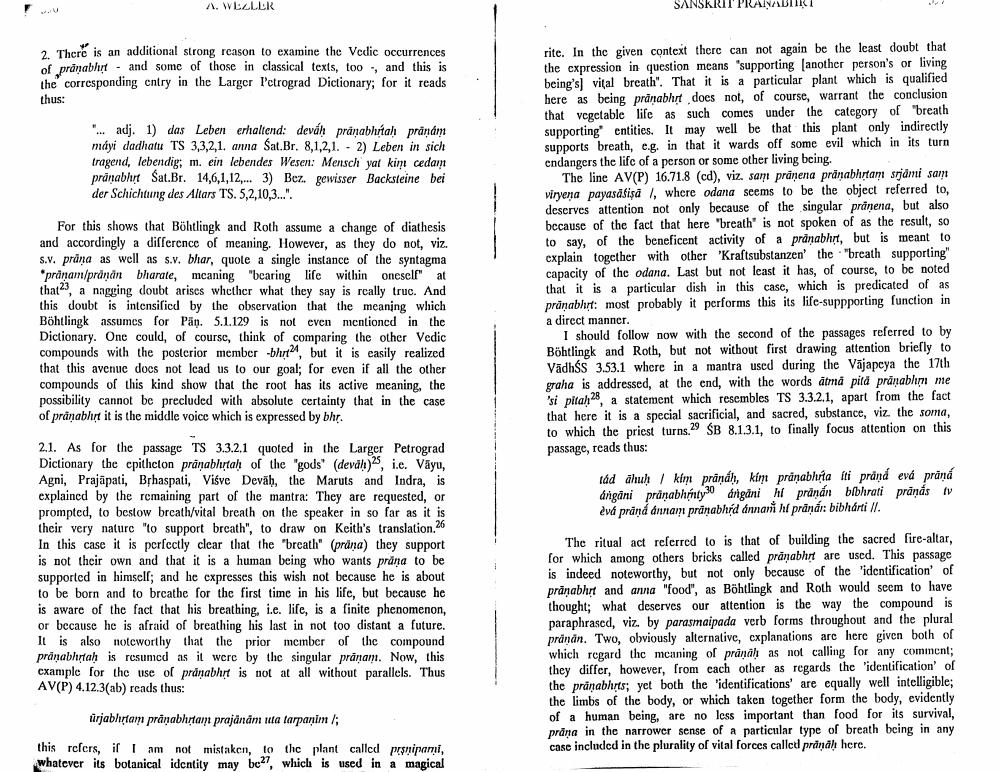

________________ A. WELLR SANSKRIT PRANADIIRI 2. There is an additional strong reason to examine the Vedic occurrences of pränabhut . and some of those in classical texts, too and this is the corresponding entry in the Larger l'etrograd Dictionary; for it reads thus: ... adj. 1) das Leben erhaltend: deváh pranabhrtah pranám máyi dadhatu TS 3,3,2,1. anna Sat.Br. 8,1,2,1. - 2) Leben in sich tragend, lebendig, m. ein lebendes Wesen: Mensch yat kim cedam pránabhrt Sat.Br. 14,6,1,12,... 3) Bez gewisser Backsteine bei der Schichtung des Altars TS. 5,2,10,3...". For this shows that Böhtlingk and Roth assume a change of diathesis and accordingly a difference of meaning. However, as they do not, viz. s.v. präna as well as s.v. bhar, quote a single instance of the syntagma "pranam/prdnan bharate, meaning "bearing life within oneself at that), a nagging doubt arises whether what they say is really true. And this doubt is intensificd by the observation that the meaning which Böhtlingk assumes for Pāṇ. 5.1.129 is not even mentioned in the Dictionary. One could, of course, think of comparing the other Vedic compounds with the posterior member bhurt but it is easily realized that this avenue docs not Icad us to our goal; for even if all the other compounds of this kind show that the root has its active meaning, the possibility cannot be precluded with absolute certainty that in the case of pränabhrt it is the middle voice which is expressed by bhr. rite. In the given context there can not again be the least doubt that the expression in question means "supporting another person's or living being's) vital breath". That it is a particular plant which is qualified here as being prānabhrt does not, of course, warrant the conclusion that vegetable life as such comes under the category of "breath supporting entities. It may well be that this plant only indirectly supports breath, e.g. in that it wards off some evil which in its turn endangers the life of a person or some other living being. The line AV(P) 16.71.8 (cd), viz. sam pranena pranabham srjdmi sam viryena payasafisa I, where odana seems to be the object referred to, deserves attention not only because of the singular pranena, but also because of the fact that here "breath' is not spoken of as the result, so to say, of the beneficent activity of a prānabhrt, but is meant to explain together with other "Krastsubstanzen' the "breath supporting" capacity of the odana. Last but not least it has, of course, to be noted that it is a particular dish in this case, which is predicated of as prunabhrt: most probably it performs this its life-suppporting function in a direct manner. I should follow now with the second of the passages referred to by Böhtlingk and Roth, but not without first drawing attention briefly to VadhśS 3.53.1 where in a mantra used during the Vajapeya the 17th graha is addressed, at the end, with the words åtmd pitd pránabhum me 'si pitan2, a statement which resembles TS 3.3.2.1, apart from the fact that here it is a special sacrificial, and sacred, substance, viz the soma, to which the pricst turns.29 ŚB 8.1.3.1, to finally focus attention on this passage, reads thus: tád ahuh/kim prânáh, kim pränabhría iti prdnd evá práná angani pranabhýty drgani hi pránán blbhrati pránás tv dvd prand annam pränabhíd ánnari í pránár: bibharti II. 2.1. As for the passage TS 3.3.2.1 quoted in the Larger Petrograd Dictionary the cpithelon pranabltah of the "gods" (devah)", i.e. Väyu, Agni, Prajapati, Brhaspati, Viśve Deväh, the Maruts and Indra, is explained by the remaining part of the mantra: They are requested, or prompted, to bestow breath/vital breath on the speaker in so far as it is their very nature "to support breath", to draw on Keith's translation.26 In this case it is perfectly clear that the "breath" (prana) they support is not their own and that it is a human being who wants präna to be supported in himself, and he expresses this wish not because he is about to be born and to breathe for the first time in his life, but because he is aware of the fact that his breathing, i.e. life, is a finite phenomenon, or because he is afraid of breathing his last in not too distant a future. It is also noteworthy that the prior member of the compound pränabhytah is resumed as it were by the singular prānam. Now, this example for the use of pránabhrt is not at all without parallels. Thus AV(P) 4.12.3(ab) reads thus: The ritual act referred to is that of building the sacred fire-altar, for which among others bricks called prānabhrt are used. This passage is indeed noteworthy, but not only because of the 'identification of pränabhrt and anna "food", as Böhtlingk and Roth would seem to have thought; what deserves our attention is the way the compound is paraphrased, viz. by parasmaipada verb forms throughout and the plural prdnan. Two, obviously alternative, explanations are here given both of which regard the meaning of pränahas not calling for any comment; they differ, however, from each other as regards the 'identification of the pränabhrts; yet both the identifications are equally well intelligible; the limbs of the body, or which taken together form the body, evidently of a human being, are no less important than food for its survival, präna in the narrower sense of a particular type of breath being in any case included in the plurality of vital forces called pranah here. Arjabhrfam pränabhrfam prajánám na tarpanim /; this refers, if I am not mistaken, to the plant called posipami, whatever its botanical identity may be27, which is used in a magicalPage Navigation

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11