________________

PIOTR BALCEROWICZ

IMPLICATIONS OF THE BUDDHIST-JAINA DISPUTE

manner (yad amurtari fan nityam drstam - 'whatever is imperceptible is experienced to be permanent') or negative manner (yad anityani tan mürtam drstar-'Whatever is impermanent is experienced to be perceptible')." However, Dharmakirti, in explicating two divisions of the fallacious example, namely sådhya-vikala and sadhyávyatirekin, that correspond to Sankarasvamin's sadhana-dharmasiddha and sadhyávyavrtta respectively, employs partly the same sentence, but changes the essential element in the reasoning: the statement of the object that serves as an example. The result is that we have two diff examples that can be interchanged ((SI) karmavar and (V1) paramánuvar).

I have expressed earlier the conviction that the actual contents of a proposition is rather secondary instead of saying it is of no relevance, inasmuch as the contents of a proposition is indeed entirely irrelevant structurally to the way a proof formula is formulated its role is to exemplify certain ontological and logical relations), but, on the other hand, it does play a certain role, since it conveys some ideas, being formulated with verbal means. I agree, all these remarks are perhaps not particularly original and are, at least intuitively, taken for granted by every student of Indian epistemology. Why, then, am I saying all this? 10 vious question: is there, thus, any advantage in using no symbols? Apparently there is, though it is not of logical nature, and I shall try to demonstrate this on the following pages.

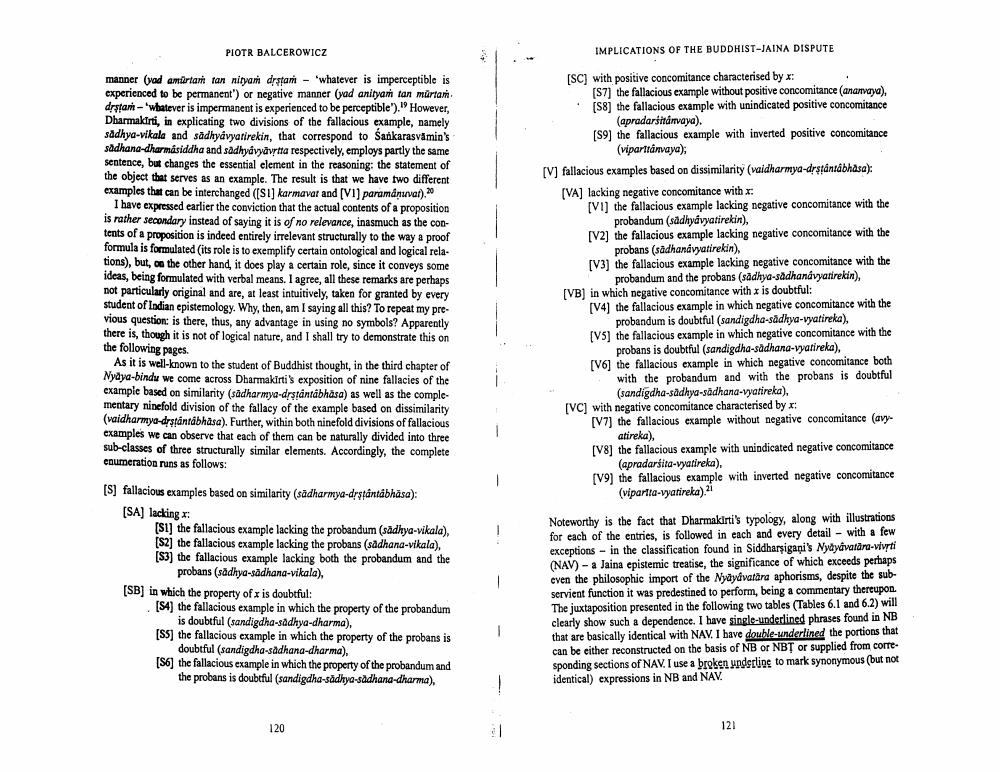

As it is well-known to the student of Buddhist thought, in the third chapter of Nyaya-bindu we come across Dharmakirti's expos example based on similarity (sadharmya-drstantábhasa) as well as the complementary ninefold division of the fallacy of the example based on dissimilarity (vaidharmya-dystantábhasa). Further, within both ninefold divisions of fallacious examples we can observe that each of them can be naturally divided into three sub-classes of three structurally similar elements. Accordingly, the complete enumeration runs as follows:

[SC] with positive concomitance characterised by X:

1871 the fallacious example without positive concomitance (ananvaya), • (58) the fallacious example with unindicated positive concomitance

(apradaršitánvaya). [59] the fallacious example with inverted positive concomitance

(viparttánvaya); [V] fallacious examples based on dissimilarity (waidharmya-drstantábhasa): [VA] lacking negative concomitance with r: (VI) the fallacious example lacking negative concomitance with the

probandum (sådhyavyatirekin), [V2] the fallacious example lacking negative concomitance with the

probans (sadhana vyatirekin), [V3) the fallacious example lacking negative concomitance with the

probandum and the probans (sādhya-sadhanávyatirekin), (VB) in which negative concomitance with x is doubtful: [V4) the fallacious example in which negative concomitance with the

probandum is doubtful (sandigdha-sadhya-vyatireka), (VS) the fallacious example in which negative concomitance with the

probans is doubtful (sandigdha-sadhana-vyatireka), (V6] the fallacious example in which negative concomitance both

with the probandum and with the probans is doubtful

(sandigdha-sadhya-sādhana-vyatireka), [VC] with negative concomitance characterised by : [V7) the fallacious example without negative concomitance (avy

atireka) [V8] the fallacious example with unindicated negative concomitance

(apradarsita-vyatireka). [V9) the fallacious example with inverted negative concomitance

(vipartta-vyatireka).21

[] fallacious examples based on similarity (sådharmya-drstäntábhasa): [SA] lacking r:

[Sl] the fallacious example lacking the probandum (sadhya-vikala), [S2] the fallacious example lacking the probans (sadhana-vikala), (53) the fallacious example lacking both the probandum and the

probans (sādhya-sādhana-vikala), (SB) in which the property of x is doubtful:

(54) the fallacious example in which the property of the probandum

is doubtful (sandigdha-sadhya-dharma), [S5] the fallacious example in which the property of the probans is

doubtful (sandigdha-sadhana-dharma), [86] the fallacious example in which the property of the probandum and

the probans is doubtful (sandigdha-sādhya-sadhana-dharma),

Noteworthy is the fact that Dharmakirti's typology, along with illustrations for each of the entries, is followed in each and every detail - with a few exceptions - in the classification found in Siddharsigani's Myayavatdra-vipti (NAV)-a Jaina epistemic treatise, the significance of which exceeds perhaps even the philosophic import of the Nyayavatāra aphorisms, despite the subservient function it was predestined to perform, being a commentary thereupon. The juxtaposition presented in the following two tables (Tables 6.1 and 6.2) will clearly show such a dependence. I have single-underlined phrases found in NB that are basically identical with NAV. I have double-underlined the portions that can be either reconstructed on the basis of NB or NBT or supplied from cortesponding sections of NAV. I use a broken underliec to mark synonymous (but not identical) expressions in NB and NAV.

120

121