________________

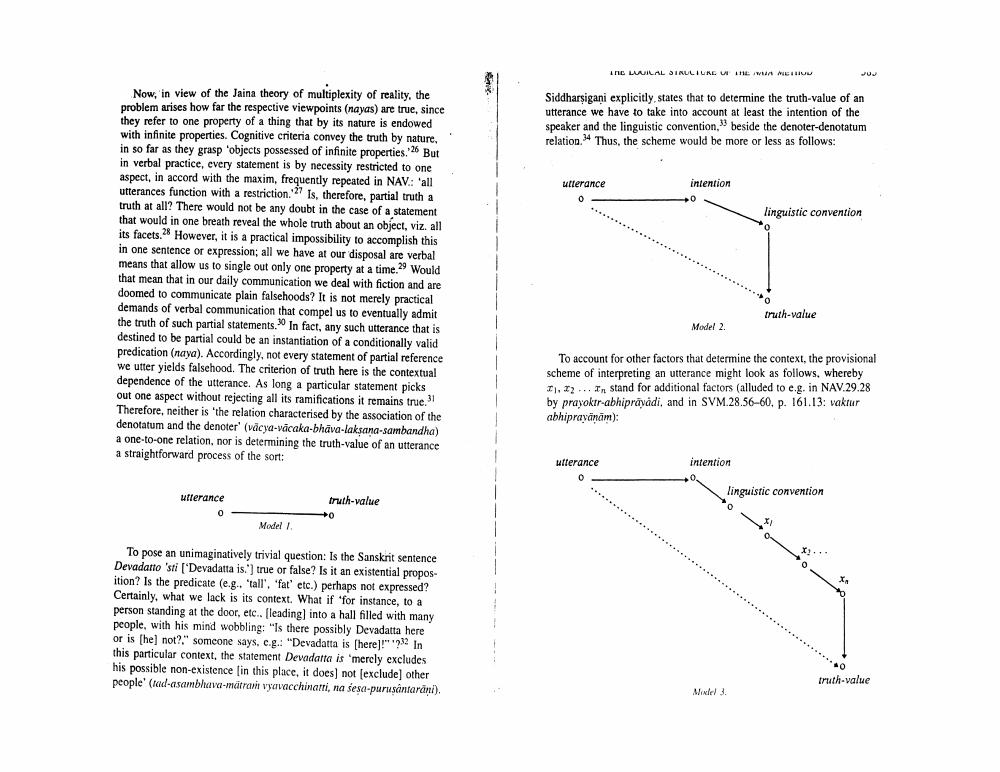

INC WILAL STALIUKE I WA MUHIMU Siddharşigani explicitly states that to determine the truth-value of an utterance we have to take into account at least the intention of the speaker and the linguistic convention, beside the denoter-denotatum relation. Thus, the scheme would be more or less as follows:

ulterance

intention

0

linguistic convention

Now, in view of the Jaina theory of multiplexity of reality, the problem arises how far the respective viewpoints (nayas) are true, since they refer to one property of a thing that by its nature is endowed with infinite properties. Cognitive criteria convey the truth by nature, in so far as they grasp 'objects possessed of infinite properties. 26 But in verbal practice, every statement is by necessity restricted to one aspect, in accord with the maxim, frequently repeated in NAV: 'all utterances function with a restriction.? Is therefore, partial truth a truth at all? There would not be any doubt in the case of a statement that would in one breath reveal the whole truth about an object, viz. all its facets. However, it is a practical impossibility to accomplish this in one sentence or expression, all we have at our disposal are verbal means that allow us to single out only one property at a time. Would that mean that in our daily communication we deal with fiction and are doomed to communicate plain falsehoods? It is not merely practical demands of verbal communication that compel us to eventually admit the truth of such partial statements. In fact, any such utterance that is destined to be partial could be an instantiation of a conditionally valid predication (naya). Accordingly, not every statement of partial reference we utter yields falsehood. The criterion of truth here is the contextual dependence of the utterance. As long a particular statement picks out one aspect without rejecting all its ramifications it remains true.31 Therefore, neither is the relation characterised by the association of the denotatum and the denoter' (vācya-vācaka-bhava-laksana-sambandha) a one-to-one relation, nor is determining the truth-value of an utterance a straightforward process of the sort:

truth-value

Model 2.

To account for other factors that determine the context, the provisional scheme of interpreting an utterance might look as follows, whereby 11.12 ... In stand for additional factors alluded to e.g. in NAV.29.28 by prayoker abhiprayadi, and in SVM.28.56-60, p. 161.13. vaktur abhipravānām):

utterance

intention

linguistic convention

utterance

truth-value

Modell

To pose an unimaginatively trivial question: Is the Sanskrit sentence Devadatto 'sti ('Devadatta is.] true or false? Is it an existential proposition? Is the predicate (e.g.. "tall', 'fat' etc.) perhaps not expressed? Certainly, what we lack is its context. What if "for instance, to a person standing at the door, etc.. [leading) into a hall filled with many people, with his mind wobbling: "Is there possibly Devadatta here or is (he) not?" someone says. c.g.: "Devadatta is (here]!" In this particular context, the statement Devadatta is 'merely excludes his possible non-existence in this place, it does not exclude other people (tad-asambhava-matrani vyavacchinarri, na sesa-purusantarani).

truth-value

Mile 3.