________________

मार्च २०१०

discriminated, if necessary with the help of the method of perspective variation in time. To what extent ancient Jain philosophers would have agreed with Aristotle on this point is a question which can only be clearly answered in a separate study. It seems to me that the Jain theory of time is fundamental, also for Jain perspectivism.

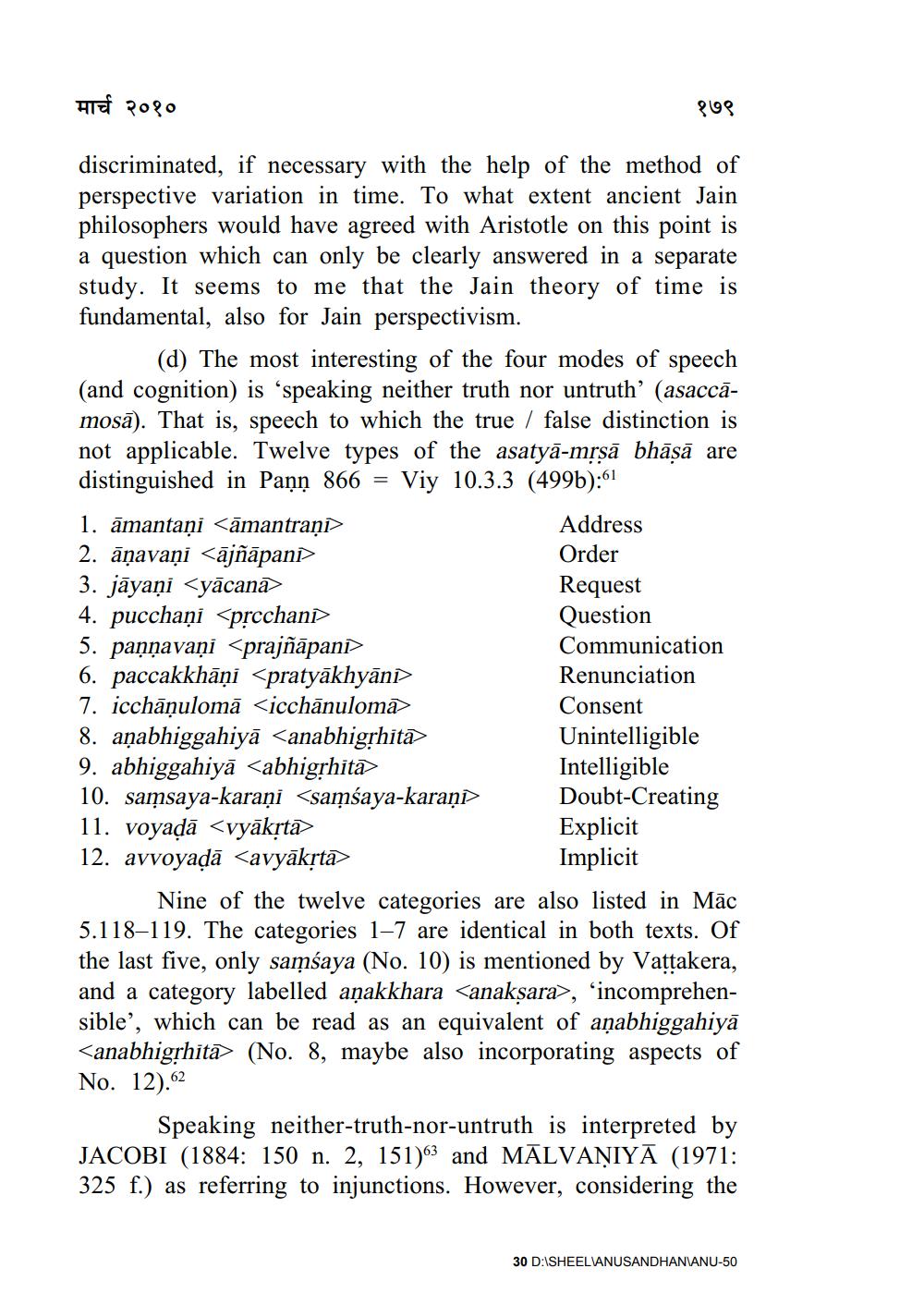

(d) The most interesting of the four modes of speech (and cognition) is 'speaking neither truth nor untruth' (asaccamosa). That is, speech to which the true false distinction is not applicable. Twelve types of the asatya-mṛṣā bhāṣā are distinguished in Pann 866 Viy 10.3.3 (499b):61

1. āmantaṇī <āmantraṇī>

2. āṇavaṇī <ājñāpani

3. jāyaṇi <yācanā

4. pucchani <prcchani

=

5. pannavani <prajñāpani> 6. paccakkhāņi <pratyākhyānī>

7. icchāņulomā <icchanuloma

8. aṇabhiggahiyā <anabhigṛhita>

9. abhiggahiya <abhigṛhita> 10. samsaya-karaṇi <samśaya-karaṇī 11. voyaḍā <vyākṛtā

12. avvoyaḍā <avyākṛtā>

१७९

Address

Order

Request

Question

Communication

Renunciation

Consent

Unintelligible

Intelligible Doubt-Creating Explicit

Implicit

Nine of the twelve categories are also listed in Mac 5.118-119. The categories 1-7 are identical in both texts. Of the last five, only samsaya (No. 10) is mentioned by Vaṭṭakera, and a category labelled aṇakkhara <anakṣara>, 'incomprehensible', which can be read as an equivalent of aṇabhiggahiyā <anabhigṛhita (No. 8, maybe also incorporating aspects of No. 12).62

Speaking neither-truth-nor-untruth is interpreted by JACOBI (1884: 150 n. 2, 151)63 and MĀLVAṆIYĀ (1971: 325 f.) as referring to injunctions. However, considering the

30 D:\SHEELVANUSANDHANIANU-50