________________

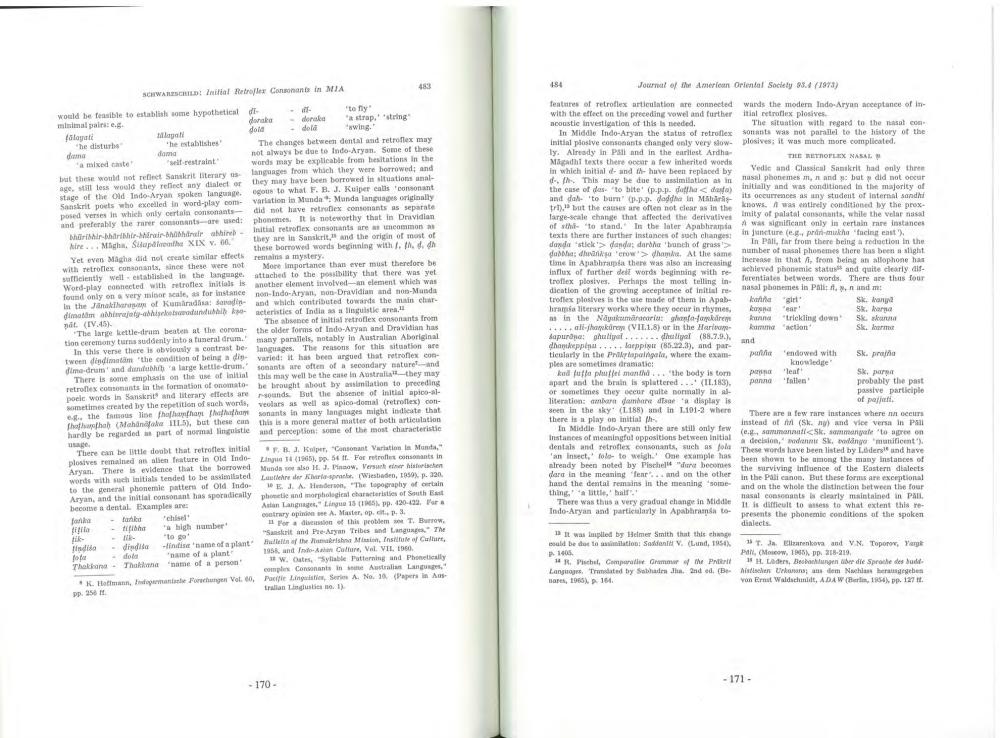

would be feasible to establish some hypothetical di

minimal pairs: e.g.

faloyati

SCHWARZSCHILD: Initial Retroflex Consonants in MIA

"he disturbs

Mlapati 'he establishes dama

dama

a mixed caste "self-restraint" but these would not reflect Sanskrit literary as age, still less would they reflect any dialect or stage of the Old Indo-Aryan spoken language. Sanskrit poets who excelled in word-play composed verses in which only certain consonantsand preferably the rarer consonants-are used: bhribhir-bharibhir-hirair-bhabharair abhirehire... Magha, Sisupalovatha XIX v. 66.

Yet even Magha did not create similar effects with retroflex consonants, since these were not sufficiently well established in the language. Word-play connected with retroflex initials is found only on a very minor scale, as for instance In the Janakiharanam of Kumaradása: saradindimatam abhimrajety-abhisekostsamadundubbiḥ kaopdt. (IV.45).

The large kettle-drum beaten at the coronation ceremony turns suddenly into a funeral drum. In this verse there is obviously a contrast be tween dindimatam 'the condition of being a dip dime-drum and dandubhib 'a large kettle-drum." There is some emphasis on the use of initial retroflex consonants in the formation of onomato poele words in Sanskrit and literary effects are sometimes created by the repetition of such words, eg.. the famous line fhofhamthan thathatham thathathah (Mahanafaka 111.5), but these can hardly be regarded as part of normal linguistic

usage.

tanka -titibha

doraka dola

There can be little doubt that retroflex initial plosives remained an allen feature in Old IndoAryan. There is evidence that the borrowed words with such initials tended to be assimilated to the general phonemic pattern of Old IndoAryan, and the initial consonant has sporadically

become a dental. Examples are: Janka 'chisel

fifita

a high number "to go"

-findise 'name of a plant "name of a plant 'name of a person'

The changes between dental and retroflex may not always be due to Indo-Aryan. Some of these words may be explicable from hesitations in the languages from which they were borrowed; and they may have been borrowed in situations analogous to what F. B. J. Kuiper calls 'consonant variation in Munda: Munda languages originally did not have retroflex consonants as separate phonemes. It is noteworthy that in Dravidian. Initial retroflex consonants are as uncommon as they are in Sanskrit," and the origin of most of these borrowed words beginning with 1. th. d. dh remains a mystery.

More importance than ever must therefore be attached to the possibility that there was yet another element involved-an element which was non-Indo-Aryan, non-Dravidian and non-Munda and which contributed towards the main characteristics of India as a linguistic area,"

The absence of initial retroflex consonants from the older forms of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian has many parallels, notably in Australian Aboriginal languages. The reasons for this situation are varied: it has been argued that retroflex consonants are often of a secondary nature and this may well be the case in Australia"they may be brought about by assimilation to preceding sounds. But the absence of initial apico-alveolars as well as apico-domal (retroflex) consonants in many languages might indicate that this is a more general matter of both articulation and perception: some of the most characteristic

indila dindita Jota -dola Thakkana Thakkana

K. Hoffmann, Indogermanische Forschungen Vol. 60,

pp. 256

iffdoraka deld

to fly"

"a strap, "string" awing."

483

F. B. J. Kiper, "Consonant Variation in Munda," Lingus 14 (1965), pp. 54 ft. For retrofles consonants in Munds see also H. J. Pinnow, Versuch einer historischen Lautlehre der Kharia-sprache. (Wiesbaden, 1959), p. 320. 10 E. J. A. Henderson, "The topography of certain phonetic and morphological characteristics of South East Astan Languages," Lingua 15 (1965), pp. 420-422. Para contrary opinion see A. Master, op. cit. p. 3.

-170

For a discussion of this problem so T. Burrow, "Sanskrit and Pre-Aryan Tribes and Languages. The Bulletin of the Ramakrishna Mission, Institute of Culture, 1956, and Indo-Asian Culture, Vel. VII, 1960.

W. Oates, "Syllable Patterning and Phonetically complex Consonants in see Australian Languages," Pacific Linguistics, Series A. No. 10. (Papers in Aus tralian Linglusties no. 1)

484

Journal of the American Oriental Society 93.4 (1973)

features of retroflex articulation are connected with the effect on the preceding vowel and further acoustic investigation of this is needed.

THE RETROPLEX NASAL

The situation with regard to the nasal con In Middle Indo-Aryan the status of retroflex sonants was not parallel to the history of the initial plosive consonants changed only very slow-plosives; it was much more complicated. ly. Already in Pali and in the earliest ArdhaMagadhl texts there occur a few inherited words in which initial d- and th- have been replaced by d. th. This may be due to assimilation as in the case of das to bite (p-p-p. daffha< data) and dah to burn' (p.p.p. doddha in Mahare tr), but the causes are often not clear as in the large-scale change that affected the derivatives of sthi to stand. In the later Apabhramia texts there are further instances of such changes: danda "stick"> danda; darbha 'bunch of grass"> dabtha; dhranka 'crow> dhamke. At the same

time in Apabhramia there was also an increasing influx of further deit words beginning with retroflex plosives. Perhaps the most telling indication of the growing acceptance of initial retroflex plosives is the use made of them in Apab hramia literary works where they occur in rhymes, as in the Nayakumaracaria: ghanta-jankärem .....ali-jhamküreys (VII.1.8) or in the HarivamSapurana: ghutiyal dhaliyal (88.7.9.). dhamkeppipa... laeppiņu (85.22.3), and particularly in the Prikytapaingala, where the examples are sometimes dramatic:

kad fuffa phuffel manthd... the body is torn. apart and the brain is splattered... (II.183). or sometimes they occur quite normally in alliteration: ambara dambara disa a display is seen in the sky (L188) and in L101-2 where there is a play on initial th

In Middle Indo-Aryan there are still only few Instances of meaningful oppositions between initial dentals and retroflex consonants, such as fola 'an insect, tolo- to weigh. One example has already been noted by Fischel "dura becomes dara in the meaning 'fear... and on the other hand the dental remains in the meaning 'some thing, a little, half."

There was thus a very gradual change in Middle Indo-Aryan and particularly in Apabhramsa to

wards the modern Indo-Aryan acceptance of initial retroflex plosives.

It was implied by Helmer Smith that this change could be due to assimilation: Saddani V. (Lund, 1954). P. 1405

14 R. Pischel, Comparative Grammar of the Prikrit Languages. Translated by Sabhadra Jha. 2nd ed. (Be nares, 1965), p. 164.

Vedic and Classical Sanskrit had only three

nasal phonemes m, n and s: but a did not occur initially and was conditioned in the majority of its occurrences as any student of internal sandhi knows. A was entirely conditioned by the prox imity of palatal consonants, while the velar nasal

was significant only in certain rare instances in juncture (e.g., prin-mukha 'facing east),

In Pali, far from there being a reduction in the number of nasal phonemes there has been a slight

increase in that i, from being an allophone has achieved phonemic status and quite clearly dif ferentiates between words. There are thus four and m

nasal phonemes in Pali: A.,

kana

kappa "ear kanna "trickling down kamma "action"

and

paña

pappa panna

endowed with knowledge leat 'fallen"

Sk. kang Sk. karna Sk. kanna Sk. karma

-171

Sk. praja Sk. para probably the past passive participle of pajjati.

There are a few rare instances where nn occurs

instead of fin (Sk. ng) and vice versa in Pal (eg, sammannati<Sk. sammangate to agree on a decision, dannu Sk. eodingo "munificent'). These words have been listed by Laders and have been shown to be among the many instances of the surviving influence of the Eastern dialects in the Pali canon. But these forms are exceptional and on the whole the distinction between the four nasal consonants is clearly maintained in Päll. 11 is difficult to assess to what extent this represents the phonemic conditions of the spoken

dialects.

T. Ja. Elizarenkova and V.N. Toporov, Yangk Pali, (Moscow, 1985), pp. 218-219.

15 H. Laders, Beobachtungen über die Sprache des budd Aistischen Urkanans; ans dem Nachlass herausgegeben von Ernst Waldschmidt, ADA W (Berlin, 1954), pp. 127.