________________

No. 14]

THREE INSCRIPTIONS IN BARIPADA MUSEUM

Whether the rulers mentioned in the records under study had their capital at Khijjingakōṭṭa, i.e modern Khiching in Mayurbhanj, cannot be determined. Considering, however, the facts that there is no other site in the area, which can be compared with Khiching in regard to antiquity and that some of the sculptures found at the place are earlier than the eleventh century when the Adi-Bhañjas flourished, it seems very likely that the pre-Adi-Bhañja rulers of the region had also their capital at Khijjinga-kōṭṭa. Indeed it is possible that Khiching was originally the centre of a big kingdom comprising the northern part of Mayurbhanj and the adjoining areas of Manbhum and Singbhum. But whether the Manas, possibly of Odra origin, also ruled from bere in the sixth century cannot be decided without further evidence. But it is not altogether impossible.

The geographical names mentioned in Inscription No. 1 are Vanagrama, Aranapada and Bharaḍihu. Nos. 2 and 3 also mention several localities; but the reading of the names is not beyond doubt in all cases. I am not sure about the location of any of them, although they appear to have been situated in the present District of Mayurbhanj in Orissa.

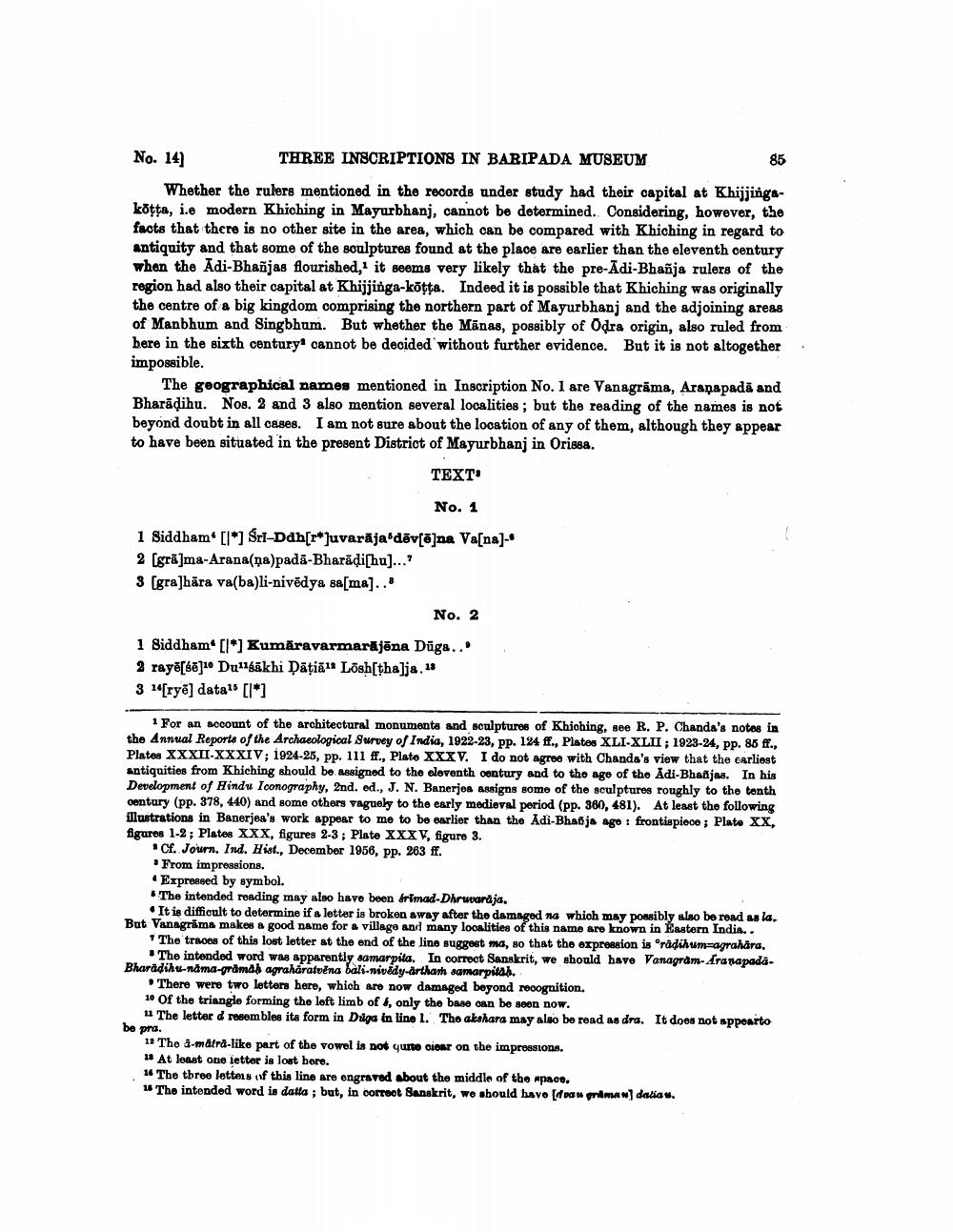

TEXT:

No. 1

1 Siddham [1] Sel-Ddh[r*Javaraja'döv[5]na Va[na]

2 [gr]ma-Arana(pa)padă-Bharāḍi[hu]...'

3 [grabāra va(ba)li-nivědya sa[mA]...

No. 2

1 Siddham [*] Kumāravarmarājēna Dūga...

2 raye[68] Du11akhi Dätiä" Lōsh[tha]ja. 13

3 14[rye] data1 [*]

85

1 For an account of the architectural monuments and sculptures of Khiching, see R. P. Chanda's notes in the Annual Reports of the Archaeological Survey of India, 1922-23, pp. 124 ff., Plates XLI-XLII; 1923-24, pp. 85 ff., Plates XXXII-XXXIV; 1924-25, pp. 111 ff., Plate XXXV. I do not agree with Chanda's view that the earliest antiquities from Khiching should be assigned to the eleventh century and to the age of the Adi-Bhañjas. In his Development of Hindu Iconography, 2nd. ed., J. N. Banerjes assigns some of the sculptures roughly to the tenth century (pp. 378, 440) and some others vaguely to the early medieval period (pp. 360, 481). At least the following illustrations in Banerjea's work appear to me to be earlier than the Adi-Bhañja age: frontispiece; Plate XX, figures 1-2; Plates XXX, figures 2-3; Plate XXXV, figure 3.

Cf. Journ. Ind. Hist., December 1956, pp. 263 ff.

From impressions.

Expressed by symbol.

The intended reading may also have been frimad-Dhruvaraja.

It is difficult to determine if a letter is broken away after the damaged na which may possibly also be read as la. But Vanagrama makes a good name for a village and many localities of this name are known in Eastern India..

The traces of this lost letter at the end of the line suggest ma, so that the expression is "rädihum-agrahara. The intended word was apparently samarpita. In correct Sanskrit, we should have Vanagram-AranapadaBharädihu-nama-gramah agraharatvēna bali-nivědy-artham samarpitab.

There were two letters here, which are now damaged beyond recognition.

10 Of the triangle forming the left limb of &, only the base can be seen now.

11 The letter d resembles its form in Diga in line 1. The akshara may also be read as dra. It does not appearto be pra.

12 The a-mäträ-like part of the vowel is not quite ciear on the impressions.

18 At least one letter is lost here.

14 The three letters of this line are engraved about the middle of the space.

16 The intended word is datta; but, in correct Sanskrit, we should have [feau griman) daliau.