________________

76

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

(APRIL, 1932

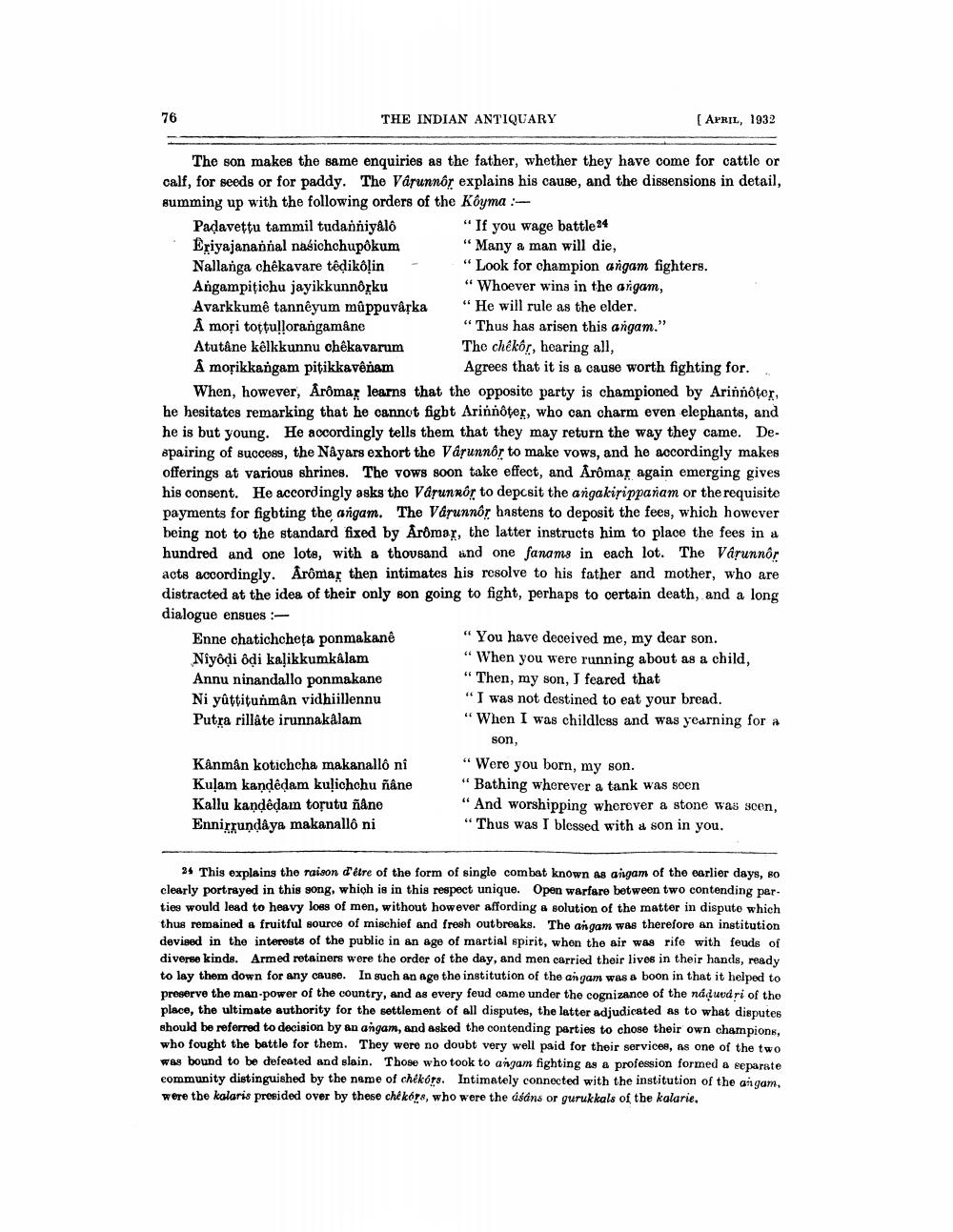

The son makes the same enquiries as the father, whether they have come for cattle or calf, for seeds or for paddy. The Vârunnor explains his cause, and the dissensions in detail, humming up with the following orders of the Koyma :

Padavettu tammil tudanñiyalo "If you wage battle 24 Eriyajanannal našichchupókum "Many a man will die, Nallanga chekavare têdikólin - "Look for champion angam fighters. Angampitichu jayikkunnorku

“Whoever wina in the argam, Avarkkumê tanneyum mũppuvárka "He will rule as the elder. A mori toţtullorangamane

"Thus has arisen this angam." Atutâne kelkkunnu chekavarum

The chêkôr, hearing all, A morikkangam piţikkavênam Agrees that it is a cause worth fighting for..

When, however, Arómar learns that the opposite party is championed by Ariñnöter, he hesitates remarking that he cannot fight Ariñnoter, who can charm even elephants, and he is but young. He accordingly tells them that they may return the way they came. Despairing of success, the Nåyars exhort the Vârunnôr to make vows, and he accordingly makes offerings at various shrines. The vows soon take effect, and Arômar again emerging gives his consent. He accordingly asks the Vârunrôr to deposit the angakirippañam or the requisite payments for figbting the angam. The Vasunnor hastens to deposit the fees, which however being not to the standard fixed by Arômor, the latter instructs him to place the fees in a hundred and one lots, with a thovsand and one fanams in each lot. The Vârunnor acts accordingly. Arômar then intimates his resolve to his father and mother, who are distracted at the idea of their only son going to fight, perhaps to certain death, and a long dialogue ensues :Enne chatichcheta ponmakanê

"You have deceived me, my dear son. Niyôdi ôdi kalikkumkalam

" When you were running about as a child, Annu ninandallo ponmakane

"Then, my son, J feared that Ni yüttitunmân vidhiillennu

"I was not destined to eat your bread. Putra rillâte irunnakalam

"When I was childless and was yearning for a

son, Kanmån kotichcha makanallô ni "Were you born, my son. Kulam kandėdam kulichchu ñâne "Bathing wherever a tank was soen Kallu kandêdam torutu ñane

"And worshipping wherever a stone was scen, Ennirrundâya makanallo ni

"Thus was I blessed with a son in you.

24 This explains the raison d'étre of the form of single combat known as aigam of the earlier days, 80 clearly portrayed in this song, which is in this respect unique. Open warfare between two contending perties would lead to heavy loss of men, without however affording a solution of the matter in disputo which thus remained a fruitful source of mischief and fresh outbreaks. The angam was therefore an institution devised in the interests of the public in an age of martial spirit, whon the air was rife with feuds of diverse kinds. Armed retainers were the order of the day, and men carried their lives in their hands, ready to lay them down for any cause. In such an age the institution of the angam was a boon in that it helped to preserve the man power of the country, and as every feud came under the cognizance of the náduudri of the place, the ultimate authority for the settlement of all disputes, the latter adjudicated as to what disputes should be referred to decision by an angam, and asked the contending parties to chose their own champions, who fought the battle for them. They were no doubt very well paid for their services, as one of the two was bound to be defeated and slain. Those who took to angam fighting as a profession formed a separate community distinguished by the name of chékots. Intimately connected with the institution of the angam, were the kalaris provided over by these chékóre, who were the asans or gurukkals of the kalarie.