________________

JANUARY, 1930]

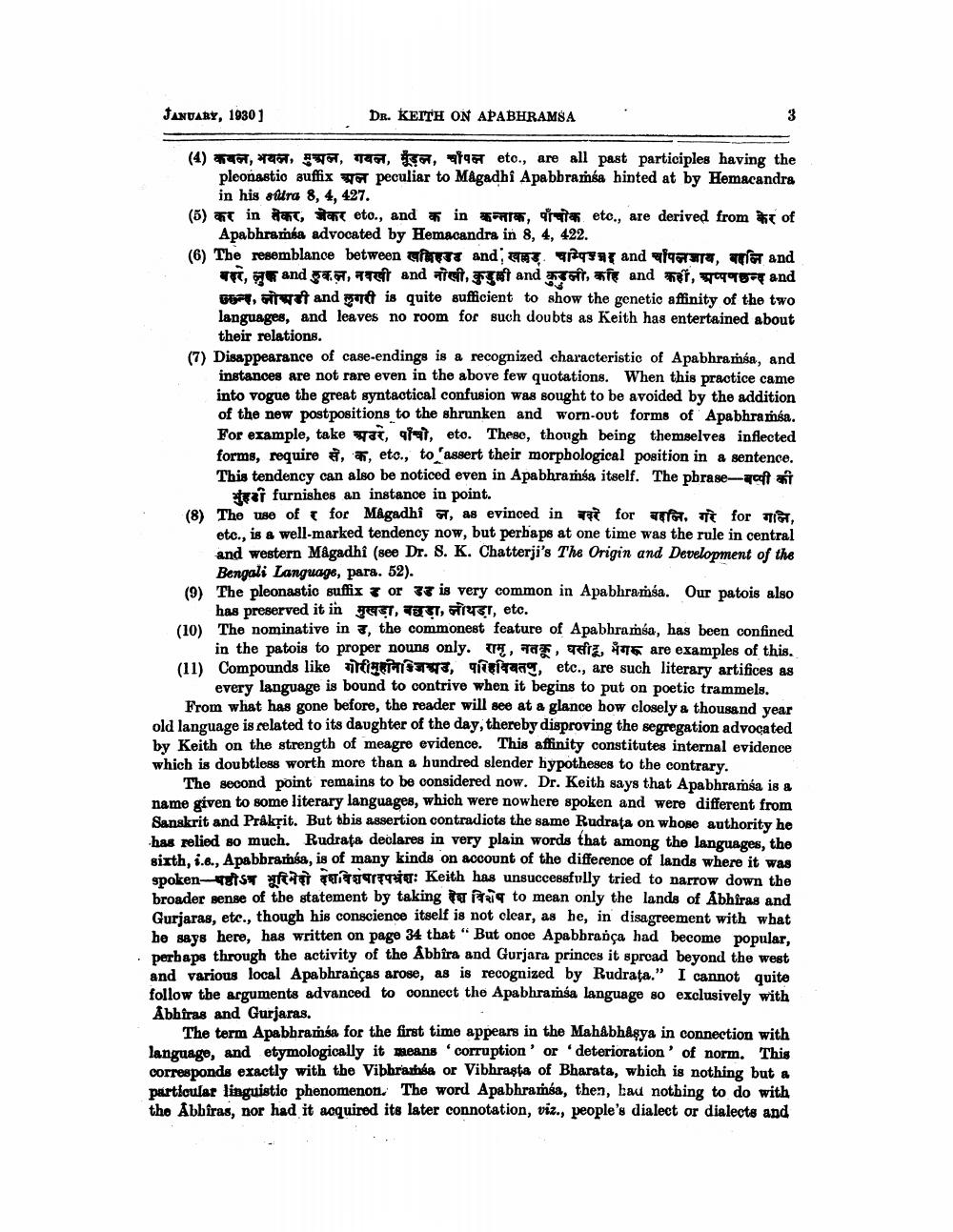

(4) कवल, भयल, मुअल, गयल, मूँडल, चपल etc. are all past participles having the pleonastio suffix W peculiar to Magadhi Apabbramsa hinted at by Hemacandra in his sudra 8, 4, 427.

(5) कर in लेकर, जेकर eto., and क in कन्ताक, पाँचोक etc. are derived from केर of

Apabhraméa advocated by Hemacandra in 8, 4, 422.

(6) The resemblance between खविहडड and खल्लड़ चम्पिअर and चपलजाय बद्दल and

बहरे, लुक and हुकल, नवखी and नोखी, कुडुली and कुडली, कहि and कहीं, अप्पणछन्द and छछन्द, जोडी and लुगरी is quite sufficient to show the genetic affinity of the two languages, and leaves no room for such doubts as Keith has entertained about their relations.

DR. KEITH ON APABHRAMSA

3

(7) Disappearance of case-endings is a recognized characteristic of Apabhraṁśa, and instances are not rare even in the above few quotations. When this practice came into vogue the great syntactical confusion was sought to be avoided by the addition of the new postpositions to the shrunken and worn-out forms of Apabhramsa. For example, take at, af, etc. These, though being themselves inflected forms, require, a, etc., to assert their morphological position in a sentence. This tendency can also be noticed even in Apabhramsa itself. The phrase-c a furnishes an instance in point.

(8) The use of र for Magadhi न, as evinced in बहरे for बद्दल, गरे for गलि, etc., is a well-marked tendency now, but perhaps at one time was the rule in central and western Magadhî (see Dr. S. K. Chatterji's The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, para. 52).

(9) The pleonastic suffix or

is very common in Apabhramsa. Our patois also has preserved it in मुखड़ा, बछड़ा, लोथड़ा, etc. (10) The nominative in, the commonest feature of Apabhramsa, has been confined

in the patois to proper nouns only. रामृ, नतकू, घसीटू, भंगरू are examples of this.. (11) Compounds like गोरीमुहान जमड, परिहवियतणु, etc., are such literary artifica every language is bound to contrive when it begins to put on poetic trammels. From what has gone before, the reader will see at a glance how closely a thousand year old language is related to its daughter of the day, thereby disproving the segregation advocated by Keith on the strength of meagre evidence. This affinity constitutes internal evidence which is doubtless worth more than a hundred slender hypotheses to the contrary.

The second point remains to be considered now. Dr. Keith says that Apabhramsa is a name given to some literary languages, which were nowhere spoken and were different from Sanskrit and Prakrit. But this assertion contradicts the same Rudrata on whose authority he has relied so much. Rudrata declares in very plain words that among the languages, the sixth, i.6., Apabbramsa, is of many kinds on account of the difference of lands where it was spoken पष्ठीऽत्र भूरिमेदो देशविशेषादपभ्रंशः Keith has unsuccessfully tried to narrow down the broader sense of the statement by taking a to mean only the lands of Abhiras and Gurjaras, etc., though his conscience itself is not clear, as he, in disagreement with what he says here, has written on page 34 that "But once Apabbrança had become popular, perhaps through the activity of the Abhira and Gurjara princes it spread beyond the west and various local Apabhranças arose, as is recognized by Rudrata." I cannot quite follow the arguments advanced to connect the Apabhramsa language so exclusively with Abhiras and Gurjaras.

The term Apabhramsa for the first time appears in the Mahâbhâşya in connection with language, and etymologically it means 'corruption' or 'deterioration' of norm. This corresponds exactly with the Vibhrama or Vibhrasta of Bharata, which is nothing but a particular linguistic phenomenon. The word Apabhramsa, then, had nothing to do with the Abbîras, nor had it acquired its later connotation, viz., people's dialect or dialects and