________________

JULY, 1924)

THE RELIGIOUS SITUATION OF THE ANDAMANESE

153

Aka-Kede

Aka-Kol

Aka-Juwoi

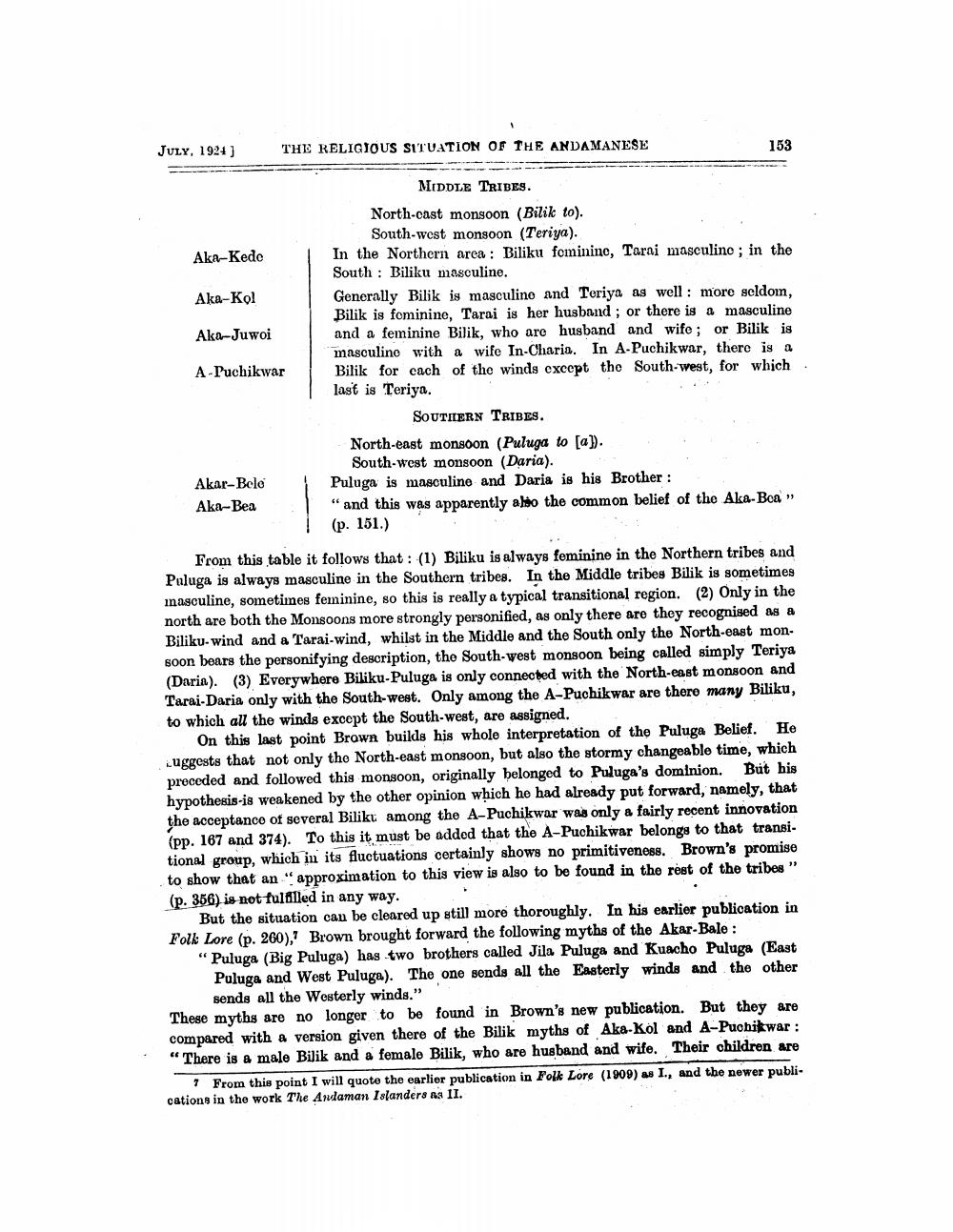

MIDDLE TRIBES. North-cast monsoon (Bilik to).

South-west monsoon (Teriya). In the Northern area : Biliku feminino, Tarni masculino; in the South : Biliku masculine. Generally Bilik is masculino and Teriya as well : more seldom, Bilik is fominine, Tarai is her husband; or there is a masculine and a feminine Bilik, who are husband and wifo; or Bilik is masculino with a wife In-Charia. In A-Puchikwar, there is a Bilik for cach of the winds except the South-west, for which last is Teriya.

SOUTIERN TRIBES. North-east monsoon (Puluga to [a]).

South-west monsoon (Daria). Puluga is masculine and Daria is his Brother : "and this was apparently also the common belief of the Aka-Boa” (p. 151.)

A -Puchikwar

Akar-Bolo Aka-Bea

From this table it follows that: (1) Biliku is always feminine in the Northern tribes and Paluga is always masculine in the Southern tribes. In the Middle tribes Bilik is sometimes inasculine, sometimes feminine, so this is really a typical transitional region. (2) Only in the north are both the Monsoons more strongly personified, as only there are they recognised as a Biliku- wind and a Tarai-wind, whilst in the Middle and the South only the North-east mon. soon bears the personifying description, the South-west monsoon being called simply Teriya (Daria). (3) Everywhere Biliku-Puluga is only connected with the North-east monsoon and Tarai.Daria only with the South-west. Only among the A-Puchikwar are there many Biliku, to which all the winds except the South-west, are assigned.

On this last point Brown builds his whole interpretation of the Puluga Belief. He uggests that not only the North-east monsoon, but also the stormy changeable time, which preceded and followed this monsoon, originally belonged to Puluga's dominion. But his hypothesis-ig weakened by the other opinion which he had already put forward, namely, that the acceptance of several Biliku among the A-Puchikwar was only a fairly recent innovation (pp. 167 and 374). To this it must be added that the A-Puchikwar belongs to that transi. tional group, which in its fluctuations certainly shows no primitiveness. Brown's promise to show that an "approximation to this view is also to be found in the rest of the tribes " (p. 356) is not fulfilled in any way.

But the situation can be cleared up still more thoroughly. In his earlier publication in Folk Lore (p. 260), Brown brought forward the following myths of the Akar-Bale : “Puluga (Big Puluga) has two brothers called Jila Puluga and Kuacho Puluga (East

Puluga and West Puluga). The one sends all the Easterly winds and the other

sends all the Westerly winds." These myths are no longer to be found in Brown's new publication. But they are compared with a version given there of the Bilik myths of Aka-Kol and A-Puohikwar: "There is a male Bilik and a female Bilik, who are husband and wife. Their children are

7 From this point I will quote the earlier publication in Folk Lore (1909) as I., and the newer publications in the work The Andaman Islanders as II.