________________

DECEMBER, 1928)

A NEW ORITICISM OF BHAVABHUTI

363

from his paternal home. Likewise Bhavabhati thought that the treacherous murder of BAli and the merciless banishment of Sita at the hand of the guileless and all-loving Rama. were improbable facts. Again, Bhavabhūti could not reconcile himself to the idea of the Ramayana as a tragedy. With so many incongruitios confronting him in the work of VAJ. miki, Bhavabhati wes led to write two dramas on the life of Rama, in which he tried to ex. pungo the four great blots from the traditional version of the story. In his Viracharita, he made Sarpanakha take the guise of Kekai and secure the banishment of Rama; he portrayed Bali as instigated by Malyaran against Rama, and thus as taking the offensive himself. In his Uttaracharita, he showed that Rama, though fully convinced of Sita's chastity and loving her from the depth of his heart, was forced by peculiar ciroumstanoes to take the drastic step, at a time when he was wholly and solely responsible for all State affairs. In the same drama, says Principal Roy, he further showed that the 'par' and 'There' portions are later additions to Valmiki's work, and that the story is erTrainasmuch as they were united in the hermitage of Valmiki.

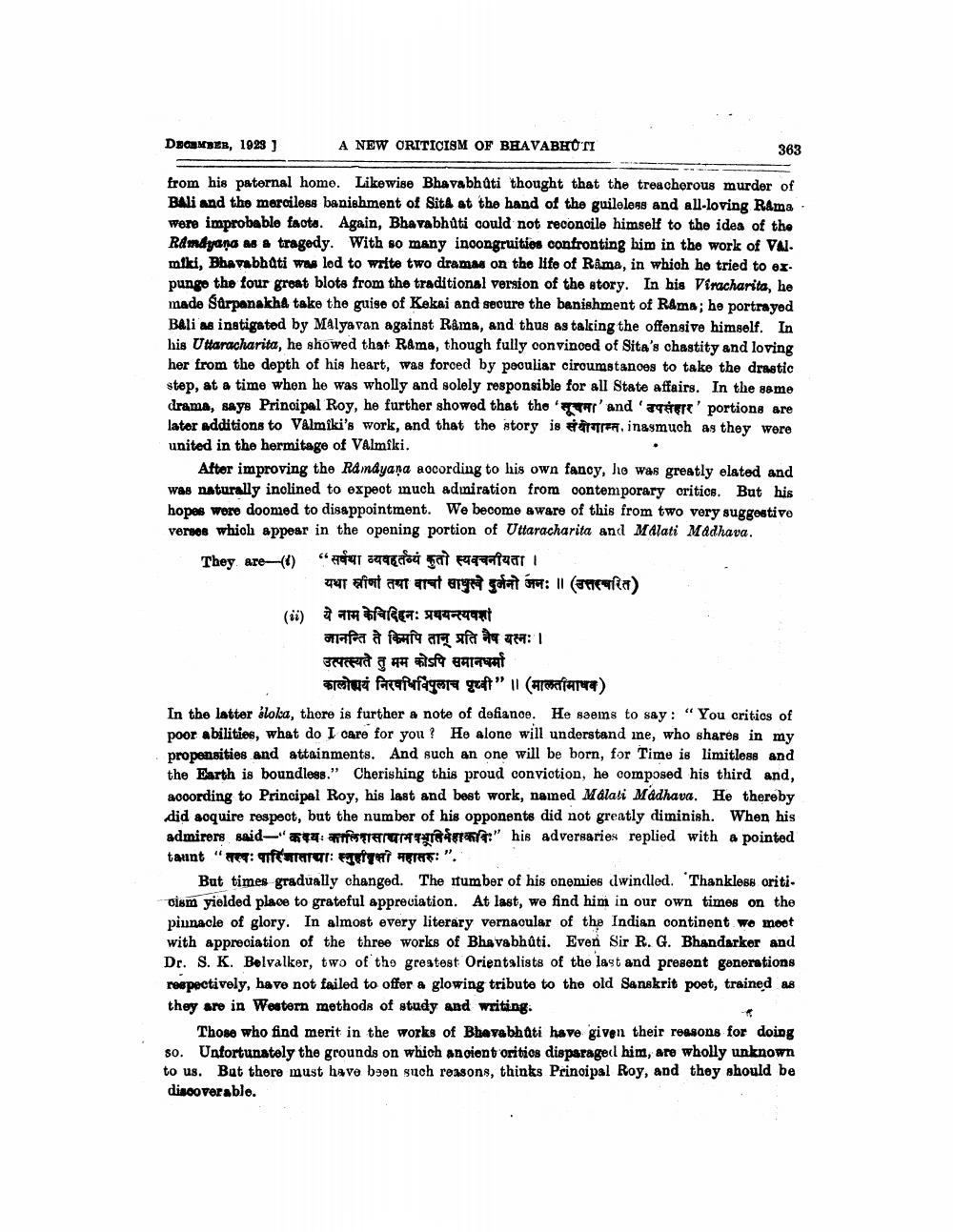

After improving the Ramayana aocording to his own fancy, he was greatly elated and was naturally inolined to expect much admiration from contemporary critics. But his hopes were doomed to disappointment. We become aware of this from two very suggestivo veries which appear in the opening portion of Uttaracharita and Malati Madhava. They are (0) 49 249€ dod gat fatal

यथा स्त्रीणां तथा वाचर्चा साधुले दुनो जनः ॥ (उत्तरचरित) ये नाम केचिदिहनः प्रथयन्स्यवश जानन्ति ते किमपि तान् प्रति नैष यस्नः । उत्पत्स्यते तु मम कोऽपि समानधर्मा

कालोधयं निरवधिविपुलाच पृथ्वी" ॥ (मालतीमाधव) In the latter sloka, there is further a note of defiance. He seems to say: "You critics of poor abilities, what do I care for you? He alone will understand ine, who shares in my propensities and attainments. And such an one will be born, for Time is limitless and the Earth is boundless." Cherishing this proud conviction, he composed his third and, according to Principal Roy, his last and best work, nained Malali Madhava. He thereby did acquire respect, but the number of his opponents did not greatly diminish. When his admirers said : OMTATART" his adversaries replied with a pointed taunt "ret: qfarelor: rg i her: ".

But times gradually changed. The itumber of his onemies dwindled. Thankless oritiDiem vielded place to grateful appreciation. At last, we find him in our own times on the pinnacle of glory. In almost every literary vernacular of the Indian continent wo meet with appreciation of the three works of Bhavabhậti. Even Sir R. G. Bhandarker and Dr. S. K. Belvalker, two of the greatest Orientalists of the last and present generations reepectively, have not failed to offer a glowing tribute to the old Sanskrit poet, trained as they are in Western methods of study and writing.

Those who find merit in the works of Bhavabhati have given their reasons for doing so. Unfortunately the grounds on which ancient oritios disparaged him, are wholly unknown to us. But there must have been such reasons, thinks Principal Roy, and they should be discoverable.