________________

August, 1923) REMARKS ON THE ANDAMAN ISLANDERS AND THEIR COUNTRY

217

tu

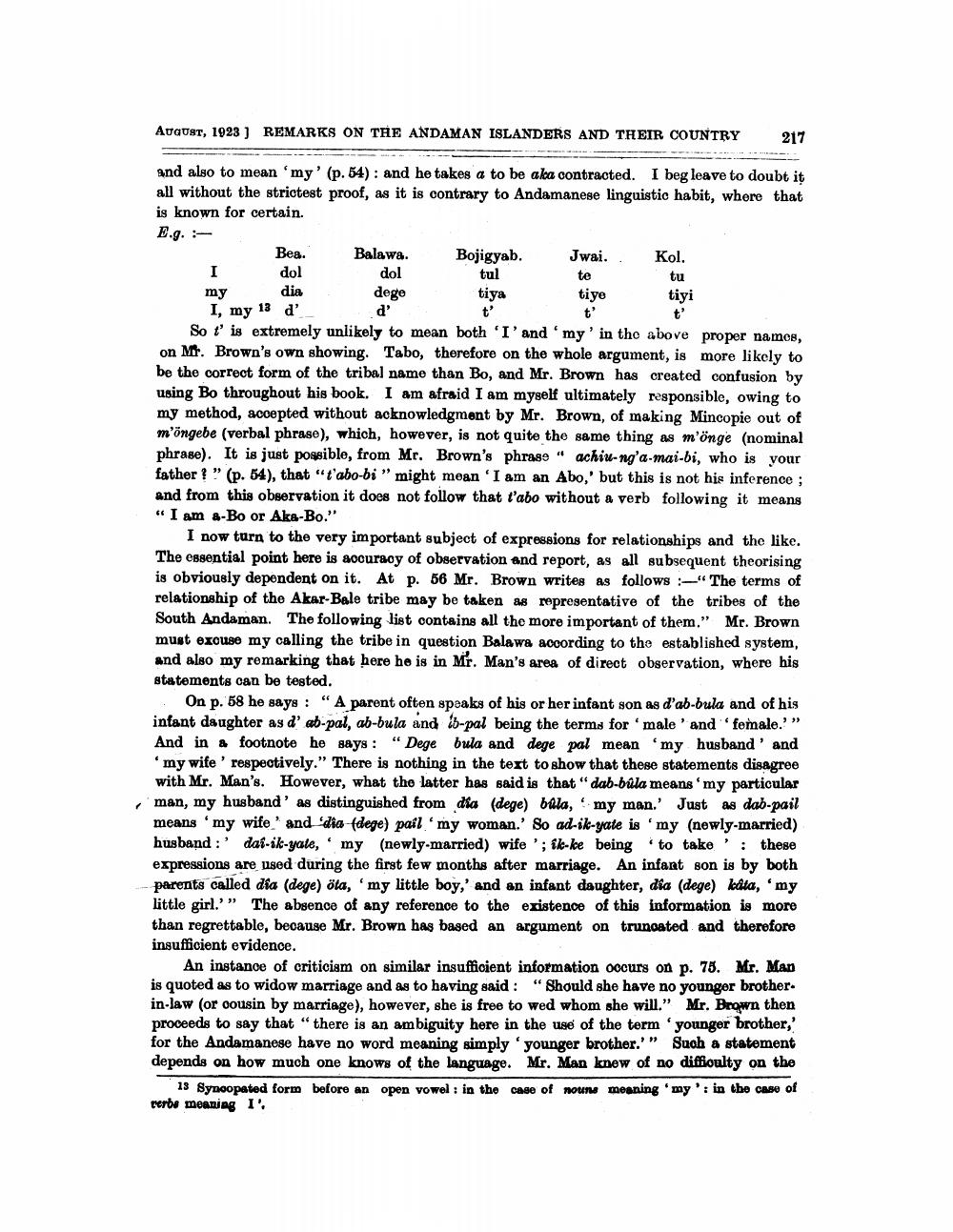

and also to mean my' (p. 54): and he takes a to be aka contracted. I beg leave to doubt it all without the striotest proof, as it is contrary to Andamanese linguistio habit, where that is known for certain. E.g. -

Bea.

Balawa. Bojigyab. Jwai.. Kol. dol dol tul

te dia dege tiya tiye

tiyi I, my 13 d'

So t' is extremely unlikely to mean both 'I' and 'my' in the above proper names, on Mr. Brown's own showing. Tabo, therefore on the whole argument, is more likely to be the correct form of the tribal name than Bo, and Mr. Brown has created confusion by using Bo throughout his book. I am afraid I am myself ultimately responsible, owing to my method, accepted without acknowledgment by Mr. Brown, of making Mincopie out of m'ongebe (verbal phrase), which, however, is not quite the same thing as m'onge (nominal phrase). It is just possible, from Mr. Brown's phrase "achiu-ng'a-mai-bi, who is your father?” (p. 54), that "t'abo-bi "might mean 'I am an Abo,' but this is not his inference ; and from this observation it does not follow that t'abo without a verb following it means "I am &-Bo or Aka-Bo."

I now turn to the very important subject of expressions for relationships and the like. The cbsential point here is accuracy of observation and report, as all subsequent theorising is obviously dependent on it. At p. 56 Mr. Brown writes as follows "The terms of relationship of the Akar-Bale tribe may be taken as representative of the tribes of the South Andaman. The following list contains all the more important of them." Mr. Brown mugt excuse my calling the tribe in question Balawa according to the established system, and also my remarking that here he is in Mr. Man's area of direct observation, where his statements can be tested.

On p. 58 he says: "A parent often speaks of his or her infant son as d'ab-bula and of his infant daughter as d'ab-pal, ab-bula and i5-pal being the terms for 'male and female.'” And in & footnote he says: "Dege bula and dege pal mean 'my husband' and

my wife' respectively." There is nothing in the text to show that these statements disagree with Mr. Man's. However, what the latter has said is that "dab-bila means 'my particular man, my husband' as distinguished from dia (dege) bila, my man. Just as dab-pail means 'my wife' and 'dia-fdege) pail' my woman.' So ad-ik-yate is 'my (newly-married) husband :' dai-ik-yale,' my (newly married) wife'; il-ke being to take these expressions are used during the first few months after marriage. An infant son is by both parents called dia (dege) öta, 'my little boy,' and an infant daughter, dia (dege) káta, 'my little girl.' ” The absence of any reference to the existence of this information is more than regrettable, because Mr. Brown has based an argument on truncated and therefore insufficient evidence.

An instance of criticism on similar insufficient information oocurs on p. 75. Mr. Man is quoted as to widow marriage and as to having said: "Should she have no younger brother. in-law (or cousin by marriage), however, she is free to wed whom she will." Mr. Brown then proceeds to say that "there is an ambiguity here in the use of the term 'younger brother, for the Andamanese have no word meaning simply 'younger brother.'” Such a statement depends on how much one knows of the language. Mr. Man knew of no diffioulty on the

13 Syncopated form before an open vowel : in the case of nouns meaning 'my ': in the case of verbe meaning I'.