________________

256

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY.

[ SEPTEMBER, 1921

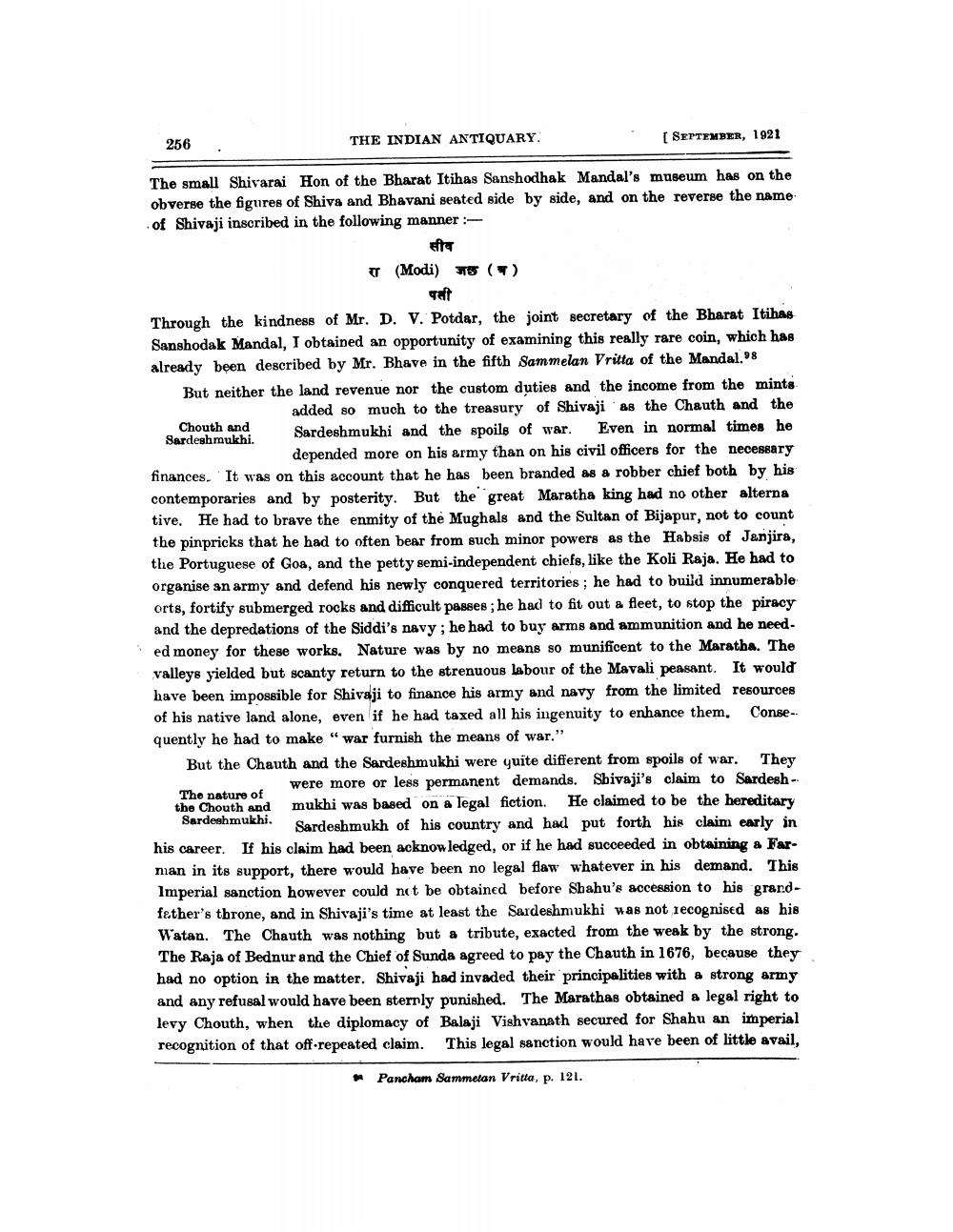

The small Shivarai Hon of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal's museum has on the obverse the figures of Shiva and Bhavani seated side by side, and on the reverse the name of Shivaji inscribed in the following manner :

सीव (Modi) 15 ()

Chouth and

Through the kindness of Mr. D. V. Potdar, the joint secretary of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodak Mandal, I obtained an opportunity of examining this really rare coin, which has already been described by Mr. Bhave in the fifth Sammelan Vritta of the Mandal." But neither the land revenue nor the custom duties and the income from the mints

added so much to the treasury of Shivaji as the Chauth and the Sardeshmukhi.

Sardeshmukhi and the spoils of war. Even in normal times he

depended more on his army than on his civil officers for the necessary finances. It was on this account that he has been branded as a robber chief both by his contemporaries and by posterity. But the great Maratha king had no other alterna tive. He had to brave the enmity of the Mughals and the Sultan of Bijapur, not to count the pinpricks that he had to often bear from such minor powers as the Habsis of Janjira, the Portuguese of Goa, and the petty semi-independent chiefs, like the Koli Raja. He had to organise an army and defend his newly conquered territories; he had to build innumerable orts, fortify submerged rocks and difficult passes, he had to fit out a fleet, to stop the piracy and the depredations of the Siddi's navy; he had to buy arms and ammunition and he need ed money for these works. Nature was by no means so munificent to the Maratha. The valleys yielded but scanty return to the strenuous labour of the Mavali peasant. It would have been impossible for Shivaji to finance his army and navy from the limited resources of his native land alone, even if he had taxed all his ingenuity to enhance them. Consequently he had to make "war furnish the means of war." But the Chauth and the Sardeshmukhi were yuite different from spoils of war. They

were more or less permanent demands. Sbivaji's claim to Sardesh - The nature of the Chouth and mukhi was based on a legal fiction. He claimed to be the hereditary Sardeshmukhi.

ah. Sardeshmukh of his country and had put forth his claim early in his career. If his claim had been acknowledged, or if he had succeeded in obtaining a Farman in its support, there would have been no legal flaw whatever in his demand. This Imperial sanction however could not be obtained before Shahu's accession to his grandfether's throne, and in Shivaji's time at least the Sardeshmukhi was not recognised as his Watan. The Chauth was nothing but a tribute, exacted from the weak by the strong. The Raja of Bednur and the Chief of Sunda agreed to pay the Chauth in 1676, because they had no option in the matter. Shivaji had invaded their principalities with a strong army and any refusal would have been sternly punished. The Marathas obtained a legal right to levy Chouth, when the diplomacy of Balaji Vishvanath secured for Shahu an imperial recognition of that off-repeated claim. This legal sanction would have been of little avail,

+

Pancham Sammelan Vritta, p. 121.