________________

266

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

[DECEMBER, 1915

languages, the infinitive ends in k, but in V. it ends in n to which k is added, as in pesumtin-ik, to strike. The termination un is therefore not specially Indian.

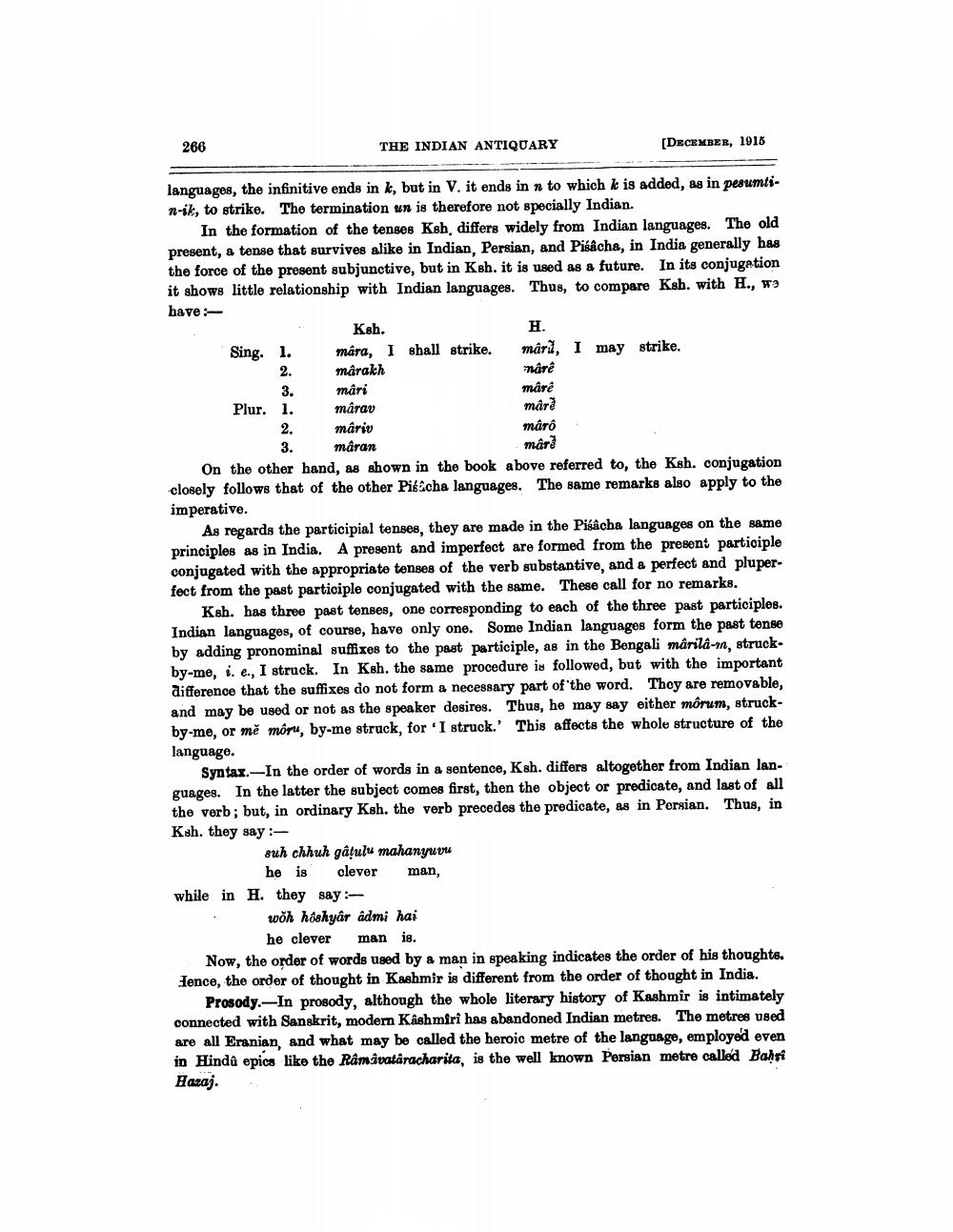

In the formation of the tenses Ksh, differs widely from Indian languages. The old present, a tense that survives alike in Indian, Persian, and Piśâcha, in India generally has the force of the present subjunctive, but in Ksh. it is used as a future. In its conjugation it shows little relationship with Indian languages. Thus, to compare Ksh. with H., we have:

Sing. 1.

2.

3.

Plur. 1.

2.

3.

Ksh.

mára, I shall strike. mârakh

H.

mára, I may strike.

mârê

mâri

mârav

mâriv

mâran

On the other hand, as shown in the book above referred to, the Ksh. conjugation closely follows that of the other Pisacha languages. The same remarks also apply to the imperative.

As regards the participial tenses, they are made in the Piśâcha languages on the same principles as in India. A present and imperfect are formed from the present participle conjugated with the appropriate tenses of the verb substantive, and a perfect and pluperfect from the past participle conjugated with the same. These call for no remarks.

mârê

mâre

while in H. they say:

mârô

mâre

Ksh. has three past tenses, one corresponding to each of the three past participles. Indian languages, of course, have only one. Some Indian languages form the past tense by adding pronominal suffixes to the past participle, as in the Bengali mârilâ-m, struckby-me, i. e., I struck. In Ksh. the same procedure is followed, but with the important difference that the suffixes do not form a necessary part of the word. They are removable, Thus, he may say either môrum, struckThis affects the whole structure of the

and may be used or not as the speaker desires. by-me, or mě moru, by-me struck, for 'I struck.' language.

Syntax. In the order of words in a sentence, Ksh. differs altogether from Indian languages. In the latter the subject comes first, then the object or predicate, and last of all the verb; but, in ordinary Ksh. the verb precedes the predicate, as in Persian. Thus, in Ksh. they say :

suh chhuh gâtulu mahanyuvu he is clever man,

woh hôshyâr âdmi hai

he clever man is.

Now, the order of words used by a man in speaking indicates the order of his thoughts. Hence, the order of thought in Kashmir is different from the order of thought in India.

Prosody. In prosody, although the whole literary history of Kashmir is intimately connected with Sanskrit, modern Kashmiri has abandoned Indian metres. The metres used are all Eranian, and what may be called the heroic metre of the language, employed even in Hindû epics like the Râmâvataracharita, is the well known Persian metre called Bahri Hazaj.