________________

xlvi

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

[CHAPTER

=

XXXV ff.), in all probability was written by them, in their new settlement, on birch-bark brought with them from their original home. But that, though written probably in Eastern Turkestan, their writers certainly were natives of north-western India, is proved by the occurrence in Parts I-III of a particular form of the letter y, hereafter called the new form," which, as will be shown in the sequel, originated in north-western India, and which, as proved by the Weber Manuscripts and all other ancient paper manuscripts discovered in Eastern Turkestan, was never in use in the latter country.70

In the second place, the Bower Manuscript, as shown in Chapter III, p. xxviii is the work ofi four distinct scribes, who wrote Parts I-III, Part IV, Parts V and VII, and Part VI respectively. The scribe who wrote the second portion (Part IV) commenced his writing on the reverse page of the last leaf of the first portion (Parts I-III), while the scribe who wrote the third portion (Parts V and VII) inscribed a remark on either of the two other portions. This circumstance proves that these three portions of the Bower Manuscript are practically contemporary writings. It is obvious that the production of Part IV cannot be earlier in date than the production of Parts I-III; and it is equally obvious that to the writer of Parts V and VII, both Part IV and Parts I-III were accessible. As to the fourth portion (Part VI), it is written for the benefit of the same person (Yaśômitra) as the beneficiary of Part VII. From the co-ordination of these facts it follows that the production of these four portions of the Bower Manuscript must be compassed by the space of about one generation, Now, as may be seen from Table II, Traverses 13-15, and as will be explained in the sequel, the writer of Parts I-III makes use, though sparingly, of the "new form" of the letter y, while the writers of Part, IV-VII employ the "old form' exclusively. It follows hence that the production of the Bower Manuscript must be referred to the very point of time when the "new form" of y was beginning to come into fashion in north-western India, that is, to the time when it was being adopted by some scribes, while it was still avoided by others.

The salient point, then, of the enquiry is to determine the epoch of the introduction of the "new form" of y into the scribal usage of north-western India, whence the writers of the Bower Manuscript must have come. The determination of that point determines the date of the production of the Bower Manuscript within very narrow limits, practically within the space of about one generation,

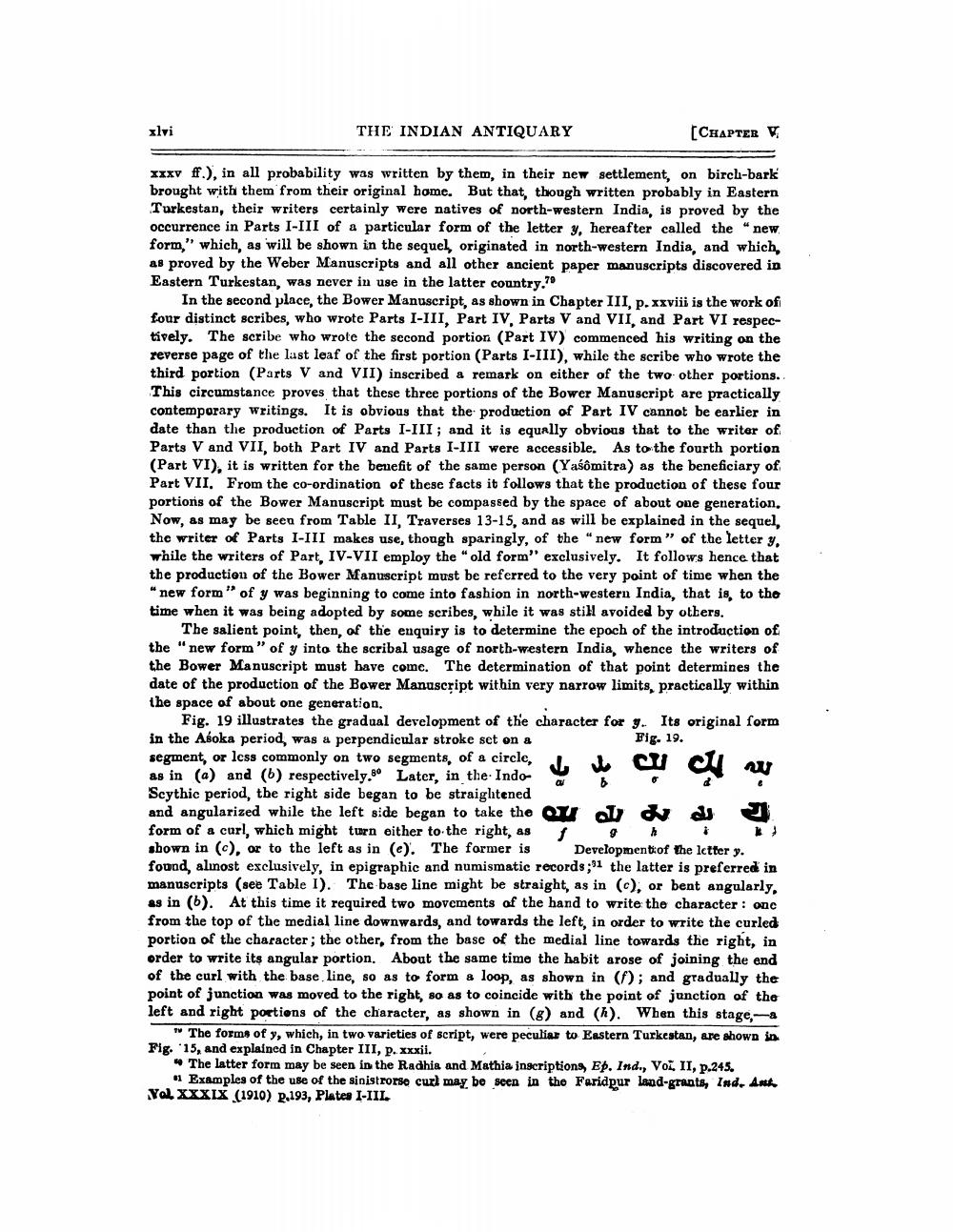

Fig. 19 illustrates the gradual development of the character for y. Its original form in the Asoka period, was a perpendicular stroke set on a

Fig. 19. segment, or less commonly on two segments, of a circle, as in (a) and (6) respectively.so Later, in the IndoScythic period, the right side began to be straightened and angularized while the left side began to take the 7 form of a curl, which might turn either to the right, as shown in (c), or to the left as in (e). The former is Development of the letter y. found, alınost exclusively, in epigraphic and numismatic records ;'1 the latter is preferred in manuscripts (see Table 1). The base line might be straight, as in (c), or bent angularly, as in (6). At this time it required two movements of the hand to write the character: one from the top of the medial line downwards, and towards the left, in order to write the curled portion of the character; the other, from the base of the medial line towards the right, in order to write its angular portion. About the same time the habit arose of joining the end of the curl with the base line, so as to form a loop, as shown in (f); and gradually the point of junction was moved to the right, so as to coincide with the point of junction of the left and right portions of the character, as shown in (8) and (h). When this stage,

The forms of y, which, in two varieties of script, were peculiar to Eastern Turkestan, are shown in Fig. 15, and explained in Chapter III, p. xxxii.

"The latter form may be seen in the Radhia and Mathia inscriptions, Ep. Ind., VOL. II, p.245.

#1 Examples of the use of the sinistrorse curl may be seen in the Faridpur land-grants, Ind. Ante Yol. XXXIX (1910) 2.193, Plates I-III

I

w