________________

120

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

[JUNE, 1914,

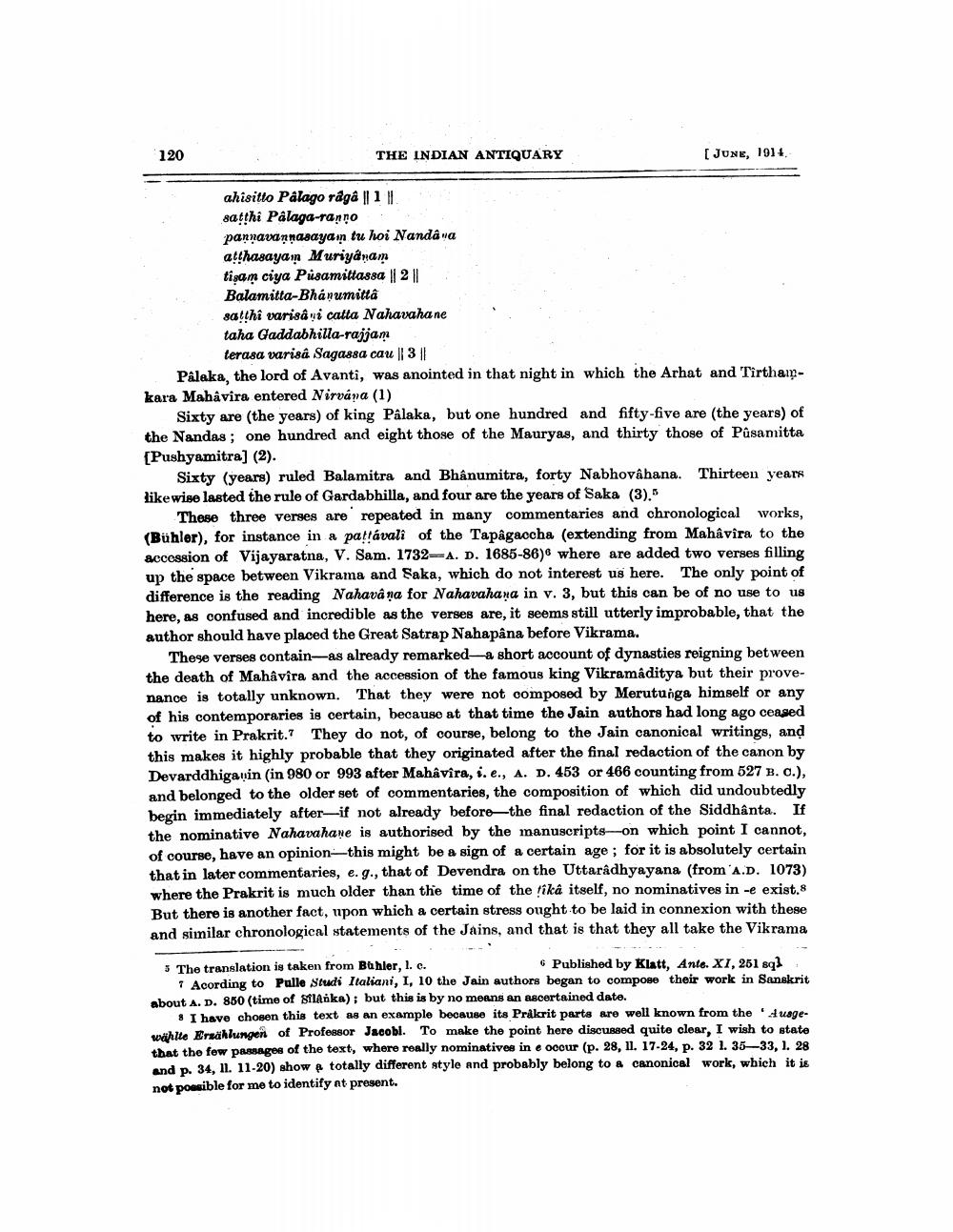

ahisitto Palago raga ||1|| satthi Palaga-ranno pannavannasayaın tu hoi Nandava atthasayaın Muriyanam tisam ciya Pusamittassa 21 Balamitta-Bhanumitta satthi varisâni catta Nahavahane taha Gaddabhilla-rajjam

terasa varisâ Sagassa cau | 3 || Palaka, the lord of Avanti, was anointed in that night in which the Arhat and Tirthaikara Mahavira entered Nirvana (1)

Sixty are the years) of king Palaka, but one hundred and fifty-five are (the years) of the Nandas; one hundred and eight those of the Mauryas, and thirty those of Pusamitta [Pushyamitra] (2).

Sixty (years) ruled Balamitra and Bhanumitra, forty Nabhovahana. Thirteen years likewise lasted the rule of Gardabhilla, and four are the years of Saka (3).

These three verses are repeated in many commentaries and chronological works, (Bühler), for instance in a pattávali of the Tapâgaocha (extending from Mahavira to the accession of Vijayaratna, V. Sam. 1732-A. D. 1685-86)e where are added two verses filling up the space between Vikrama and Saka, which do not interest us here. The only point of difference is the reading Nahavana for Nahavahana in v. 3, but this can be of no use to us here, as confused and incredible as the verses are, it seems still utterly improbable, that the author should have placed the Great Satrap Nahapana before Vikrama.

These verses contain-as already remarked—a short account of dynasties reigning between the death of Mahavira and the accession of the famous king Vikramaditya but their provenance is totally unknown. That they were not composed by Merutunga himself or any of his contemporaries is certain, because at that time the Jain authors had long ago ceased to write in Prakrit. They do not, of course, belong to the Jain canonical writings, and this makes it highly probable that they originated after the final redaction of the canon by Devarddhiganin (in 980 or 993 after Mahâvira, i. e., A. D. 453 or 466 counting from 527 B. c.), and belonged to the older set of commentaries, the composition of which did undoubtedly begin immediately after--if not already before—the final redaction of the Siddhanta. If the nominative Nahavahane is authorised by the manuscripts-on which point I cannot, of course, have an opinion—this might be a sign of a certain age; for it is absolutely certain that in later commentaries, e.g., that of Devendra on the Uttaradhyayana (from A.D. 1073) where the Prakrit is much older than the time of the lika itself, no nominatives in -e exist.8 But there is another fact, upon which a certain stress ought to be laid in connexion with these and similar chronological statements of the Jains, and that is that they all take the Vikrama

3 The translation is taken from Bühler, 1. c.

Published by Klatt, Ante. XI, 261 sq 1 Acording to Pulle Studi Italiani, I, 10 the Jain authors began to compose their work in Sanskrit about A. D. 850 (time of starka); but this is by no means an ascertained date.

8 I have chosen this text as an example because its Prikrit parts are well known from the 'dusgewählte Erzählungen of Professor Jacobl. To make the point here discussed quite clear, I wish to state that the few passages of the text, where really nominatives in e ooour (p. 28, 11. 17-24, p. 32 1. 3533, 1. 28 and p. 34, 11. 11-20) how totally different style and probably belong to a canonical work, which it is not possible for me to identify at present.