________________

xxii

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

[CHAPTER II

1 to 4, on the obverse sides. The manuscript commences with the usual symbol for coin on the obverse of the first leaf, and ends with the usual Buddhist terminal salutations and the double stroke (Chapter IV, p. xxxvii) on the top of the reverse of the fourth folio.

Part VII, which contains a portion of the same charm against snake bite (see Chapter III, pp. xxix and xxxy and Chapter VIII) is defective. It consists of two, much damaged, leaves, the first of which, on its reverse side, bears the pagination 1. The obverse has lost its inscribed surface layer of bark (p. xix), and with it the commencement of the charm. The pagination of the second leaf is lost with the broken-off margin.

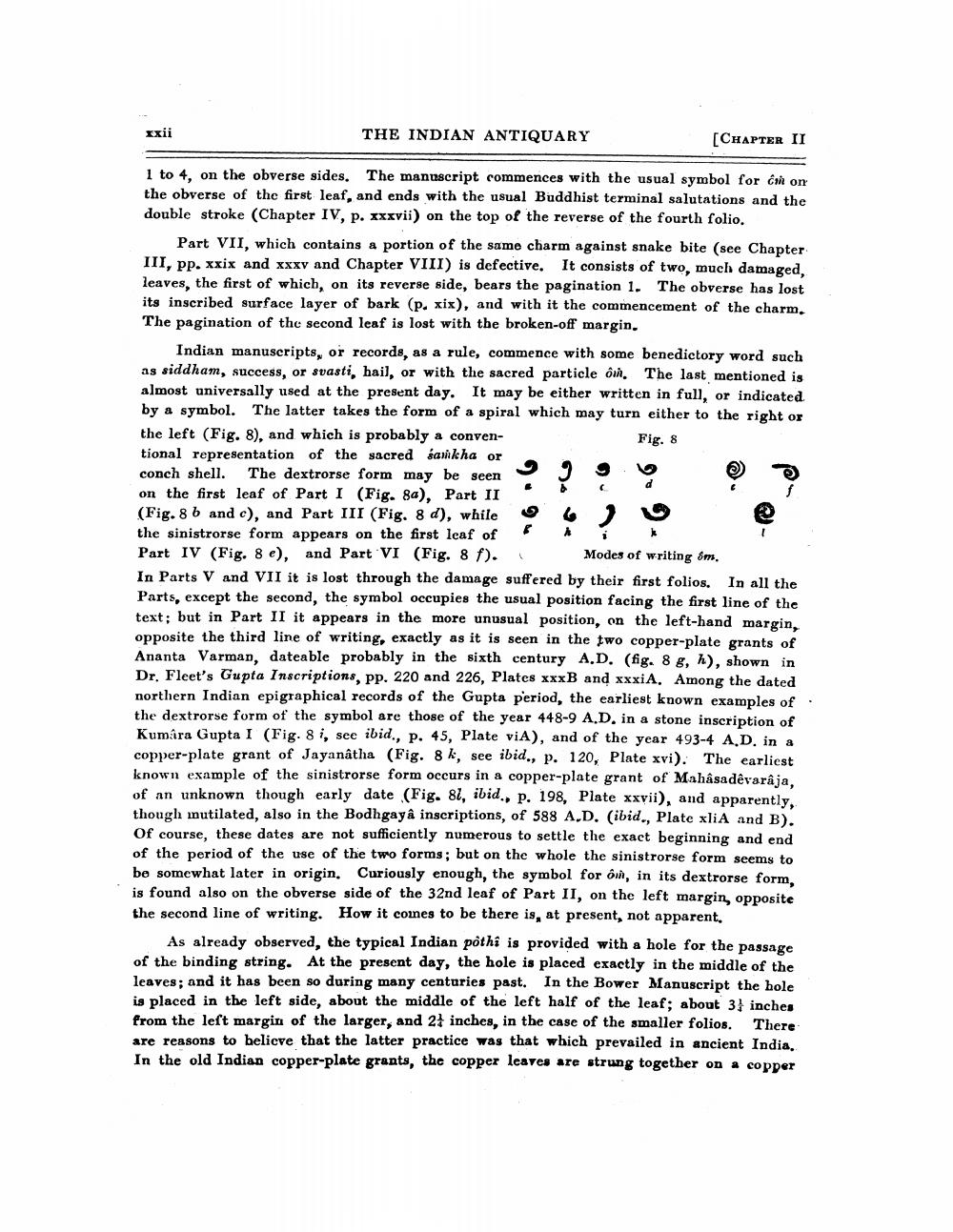

Indian manuscripts, or records, as a rule, commence with some benedictory word such as siddham, success, or svasti, hail, or with the sacred particle in. The last mentioned is almost universally used at the present day. It may be either written in full, or indicated by a symbol. The latter takes the form of a spiral which may turn either to the right or the left (Fig. 8), and which is probably a conven

Fig. 8 tional representation of the sacred sanikha or . conch shell. The dextrorse form may be seen on the first leaf of Part I (Fig. 8a), Part II (Fig. 8 b and c), and Part III (Fig. 8 d), while the sinistrorse form appears on the first leaf off Part IV (Fig. 8e), and Part VI (Fig. 8 f).

Modes of writing om. In Parts V and VII it is lost through the damage suffered by their first folios. In all the Parts, except the second, the symbol occupies the usual position facing the first line of the text; but in Part II it appears in the more unusual position, on the left-hand margin, opposite the third line of writing, exactly as it is seen in the two copper-plate grants of Ananta Varman, dateable probably in the sixth century A.D. (fig. 8 g, h), shown in Dr. Fleet's Gupta Inscriptions, pp. 220 and 226, Plates xxxB and xxxiA. Among the dated northern Indian epigraphical records of the Gupta period, the earliest known examples of the dextrorse form of the symbol are those of the year 448-9 A.D. in a stone inscription of Kumara Gupta I (Fig. 8i, see ibid., p. 45, Plate viA), and of the year 493-4 A.D. in a copper-plate grant of Jayanatha (Fig. 8 k, see ibid., p. 120, Plate xvi). The earliest known example of the sinistrorse form occurs in a copper-plate grant of Mahâsadêvarâja, of an unknown though early date (Fig. 8l, ibid., p. 198, Plate xxvii), and apparently, though mutilated, also in the Bodhgaya inscriptions, of 588 A.D. (ibid., Plate xli A and B). Of course, these dates are not sufficiently numerous to settle the exact beginning and end of the period of the use of the two forms; but on the whole the sinistrorse form seems to be somewhat later in origin. Curiously enough, the symbol for ôi, in its dextrorse form, is found also on the obverse side of the 32nd leaf of Part II, on the left margin, opposite the second line of writing. How it comes to be there is, at present, not apparent.

As already observed, the typical Indian pothi is provided with a hole for the passage of the binding string. At the present day, the hole is placed exactly in the middle of the leaves; and it has been so during many centuries past. In the Bower Manuscript the hole is placed in the left side, about the middle of the left half of the leaf; about 31 inches from the left margin of the larger, and 2 inches, in the case of the smaller folios. There are reasons to believe that the latter practice was that which prevailed in ancient India. In the old Indian copper-plate grants, the copper leaves are strung together on a copper