________________

MAY, 1913.)

INDIAN INSCRIPTIONS AND THE KAVYA.

147

grammar, for purposes of metre. A slight mistake of the kind is the use of the Atmanepada in nyavasanta (verse 15), instead of Paras maipada, though this may perhaps be excused owing to its similar use in epic poetry and on the ground of analogons mistakes met with in the kávyas. Far worse, however, is the use of the masculine form spritann=iva instead of the neuter sprisad-iva (verse 38), which has to agree with the substantive griham (verse 87). Mr. Fleet, of course, propoges to write sprisativa, but it would not at all suit the metre. Besides, with this alteration, the whole construction would not only be changed but broken up into pieces, because then the locatives in verges 89-40, would be altogether hanging in the air. With the text as we have it, sainskdritam was repaired' (verse 37) is the verb in the principal sentence with which, all the following words, which are attributes of the time, can be quite rightly connected. If, however, we write sprisativa, this itself, then, becomes the principal verb and then we must translate as follows :

37. This temple of the Sun, which the generous guild caused to be built up again, in all its parts, very stately, in order to further their renown,'

38. "That temple, which was exceedingly higb, glowing white, the resting place of the pare rays of the Sun and the Moon at their rise, touched, as it were, the sky, with its charming tarrets.'

Here the sentence is complete, and there is no verb with which the following words, after five hundred and twenty-nine years had passed, on the second day of the bright half of the lovely month of Tapasya' can be construed. Thus Vatsabhatti cannot be freed from the charge of having used a wrong gender, out of regard for the metre. We may suppose that he might have been conscious of the fault but that he might have consoled himself with the beautiful principle :

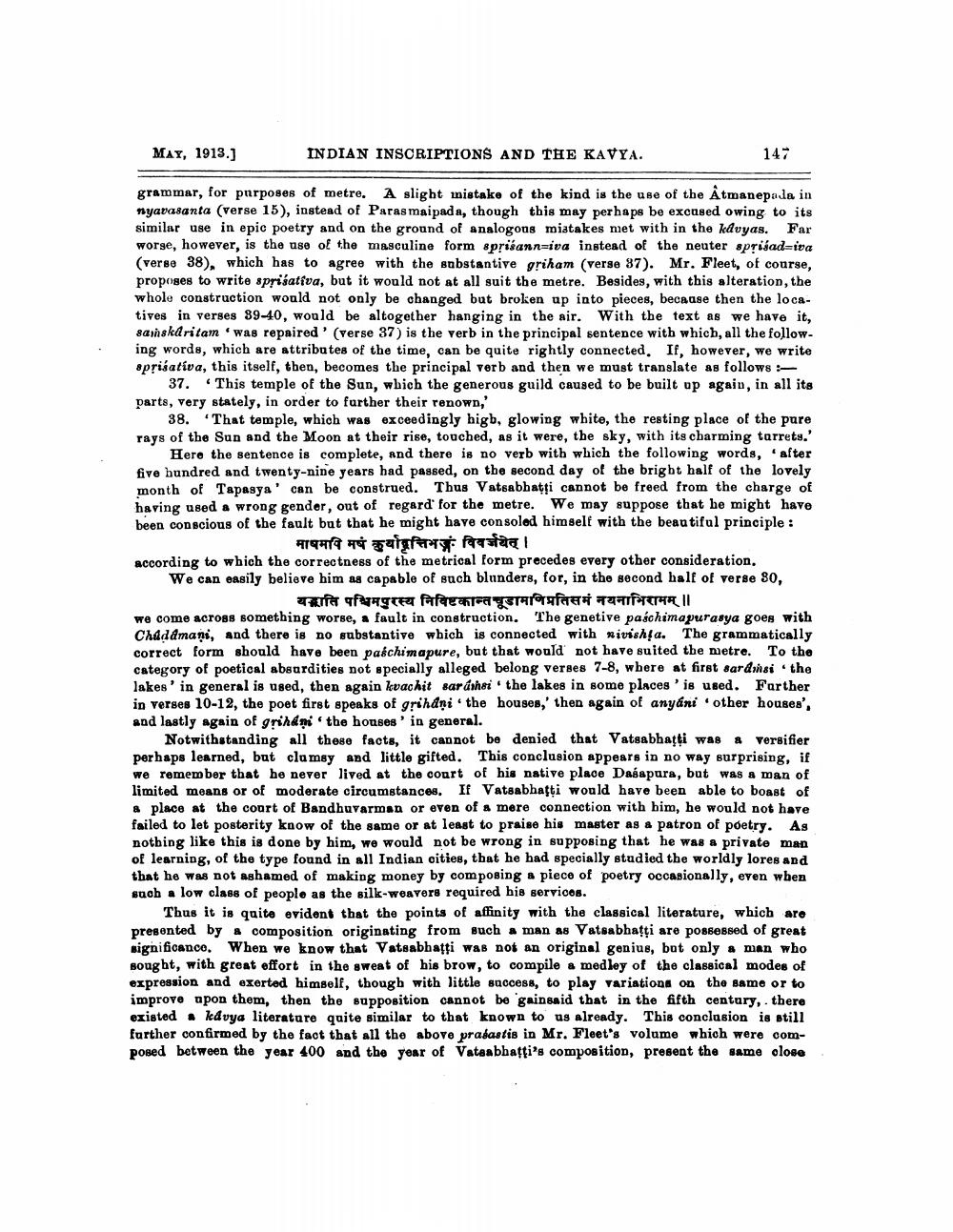

माषमपि मषं कुयोवत्तिमजं विवर्जयेत् । according to which the correctness of the metrical form precedes every other consideration. We can easily believe him as capable of such blunders, for, in the second half of verse 30,

याति पधिमपुरस्य निविष्टकान्तचूडामणिप्रतिसमं नयनाभिरामम् ॥ we come across something worse, a fault in construction. The genetive paschimapurasya goes with Chadamani, and there is no substantive which is connected with rivishļa. The grammatically correct form should have been paschimapure, but that would not have suited the metre. To the category of poetical absurdities not specially alleged belong verses 7-8, where at first sardineithe lakes' in general is used, then again kvachit sardinei the lakes in some places is used. Farther in verses 10-12, the poet first speaks of grihani. the houses,' then again of anyáni other houses', and lastly again of griheni 'the houses in general.

Notwithstanding all these facts, it cannot be denied that Vatsabhagti was a versifier per baps learned, but clamsy and little gifted. This conclusion appears in no way surprising, if we remember that he never lived at the court of his native place Dasapura, but was a man of limited means or of moderate circumstances. If Vatsabhatti would have been able to boast of & place at the court of Bandhuvarman or even of a mere connection with him, he would not have failed to let posterity know of the same or at least to praise his master as a patron of poetry. As nothing like this is done by him, we would not be wrong in supposing that he was a private man of learning, of the type found in all Indian cities, that he had specially studied the worldly lores and that he was not ashamed of making money by composing a piece of poetry occasionally, even when such a low class of people as the silk-weavers required his servicos.

Thus it is quite evident that the points of affinity with the classical literature, which are presented by a composition originating from such a man as Vatsabhatti are possessed of great significance. When we know that Vatsabhatti was not an original genius, but only a man who sought, with great effort in the sweat of his brow, to compile a medley of the classical modes of expression and exerted himself, though with little success, to play variations on the same or to improve apon them, then the supposition cannot be gainsaid that in the fifth century, there existed « kdvya literature quite similar to that known to us already. This conclusion is still further confirmed by the fact that all the above prasastis in Mr. Fleet's volume which were composed between the year 400 and the year of Vateabhatti's composition, present the same close