________________

96

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

(APRIL, 1913.

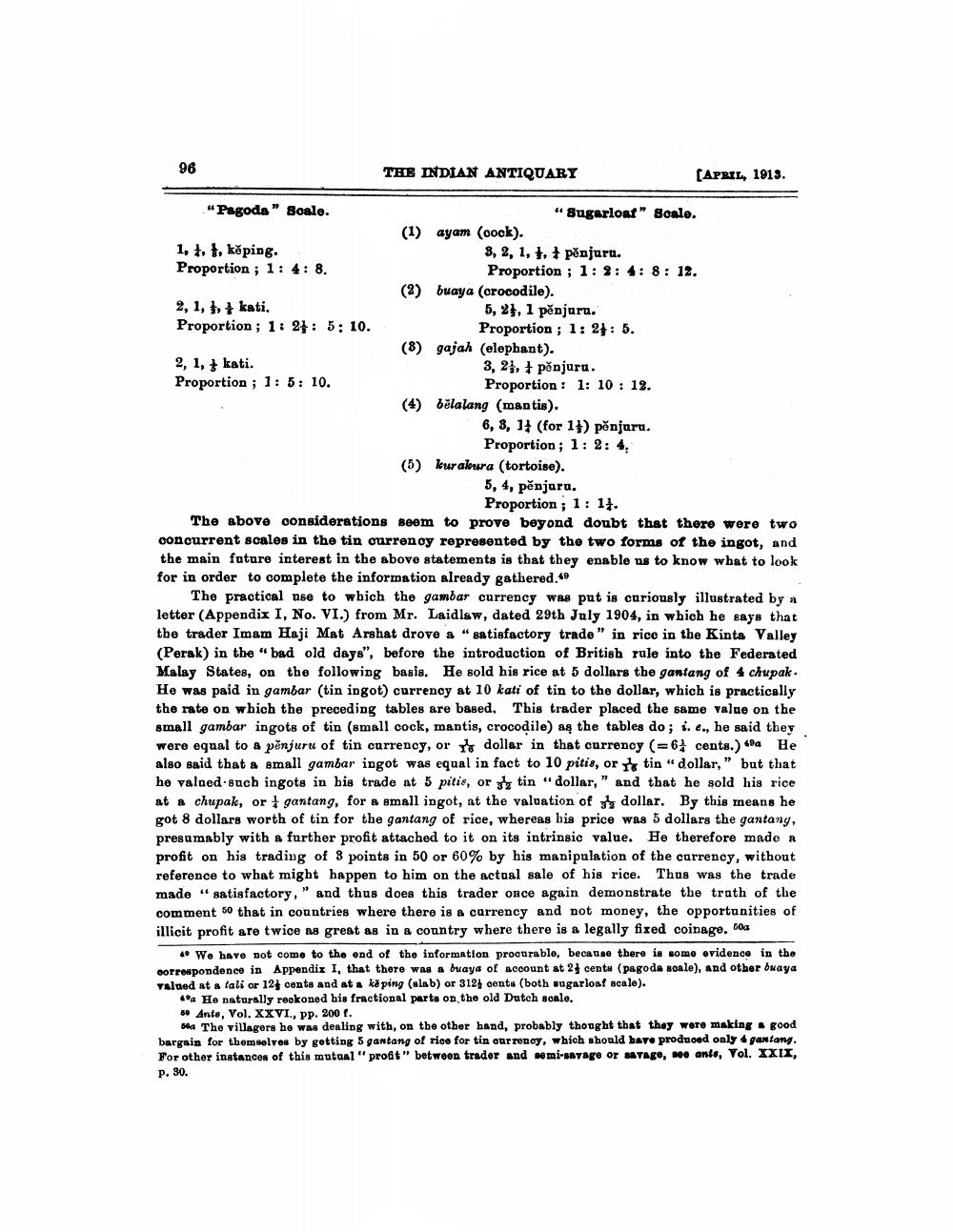

“Pagoda” Soale.

"Sugarloaf" Scale.

(1) ayam (cock). 1, t. I, képing.

3, 2, 1, 1, 1 pěnjuru. Proportion ; 1: 4: 8.

Proportion ; 1: 2: 4:8: 12.

(2) buaya (crocodile). 2, 1, $ + kati.

5, 2, 1 pěnjurn. Proportion; 1: 21: 5:1

Proportion ; 1: 21: 5.

(8) gajah (elephant). 2, 1, 1 kati.

3, 2, 1 pěnjuru. Proportion ; 1: 5: 10.

Proportion : 1: 10 : 12. (4) bělalang (mantis).

6, 8, 14 (for 1}) penjuru.

Proportion; 1: 2: 4: (5) kurakura (tortoise).

5, 4, pěnjara.

Proportion; 1: 14. The above considerations seem to prove beyond doubt that there were two concurrent scales in the tin currenoy represented by the two forms of the ingot, and the main future interest in the above statements is that they enable us to know what to look for in order to complete the information already gathered.

The practical use to which the gambar currency was put is cariously illustrated by a letter (Appendix I, No. VI.) from Mr. Laidlaw, dated 29th July 1904, in which he says that the trader Imam Haji Mat Arshat drove a "satisfactory trade" in rice in the Kinta Valley (Perak) in the "bad old days", before the introduction of British rule into the Federated Malay States, on the following basis. He sold his rice at 5 dollars the gantang of 4 chupak. He was paid in gambar (tin ingot) currency at 10 kati of tin to the dollar, which is practically the rate on which the preceding tables are based. This trader placed the same value on the small gambar ingots of tin (small cock, mantis, crocodile) as the tables do; i. e., he said they were equal to a penjuru of tin currency, or i dollar in that currency (= 64 cents.) Sa He also said that a small gambar ingot was equal in fact to 10 pitis, or it tin " dollar," but that he valaed.such ingots in his trade at 5 pitis, or 3 tin "dollar," and that he sold his rice at a chupak, or gantang, for a small ingot, at the valuation of dollar. By this means he got 8 dollars worth of tin for the gantang of rice, whereas his price was 5 dollars the gantany, presumably with a further profit attached to it on its intrinsic value. He therefore made a profit on his trading of 3 points in 50 or 60% by his manipulation of the currency, without reference to what might happen to him on the actual sale of his rice. Thus was the trade made " satisfactory," and thus does this trader once again demonstrate the truth of the comment 50 that in countries where there is a currency and not money, the opportunities of illicit profit are twice as great as in a country where there is a legally fixed coinage. Od

* We have not come to the end of the information procurable, because there is some evidence in the oorrenpondence in Appendix I, that there was a buaya of account at 2 cents (pagoda Boale), and other buaya valued at a tali or 12 cents and at a köping (slab) or 312 cents (both sugarloaf acalo).

4* Ho naturally reokoned his fractional parts on the old Dutch soalo. 5. Ante, Vol. XXVI., PP. 200 f.

Ba The villagers he was dealing with, on the other hand, probably thought that they were making good bargain for themselves by getting 5 gantang of rice for tin our renoy, which should bare produoed only 4 gantang. For other instances of this mutual" profit" between trader and somi-savage or Tag, mo ante, Vol. XXII, P. 90.