________________

20

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY.

The next question of interpretation concerns the word anusamyana, which Senart had no hesitation in translating as rendez-vous, assemblée.' Anusamydna, according to him (Inecr. de Piyadasi, Vol. I, p. 80), marquerait bien, par sa constitution étymologique, un vaste rendez-vous, une réunion publique, tenue dans certains lieux désignés.'

[JANUARY, 1908.

But Professor Kern seems to be right in translating tour of inspection.' The word anusamyana, as Mr. Thomas observes, occurs in both Brahmanical and Buddhist Sanskrit. Samyana, means a tour, and the force of anu is to express the notion of to one place after another.'

-

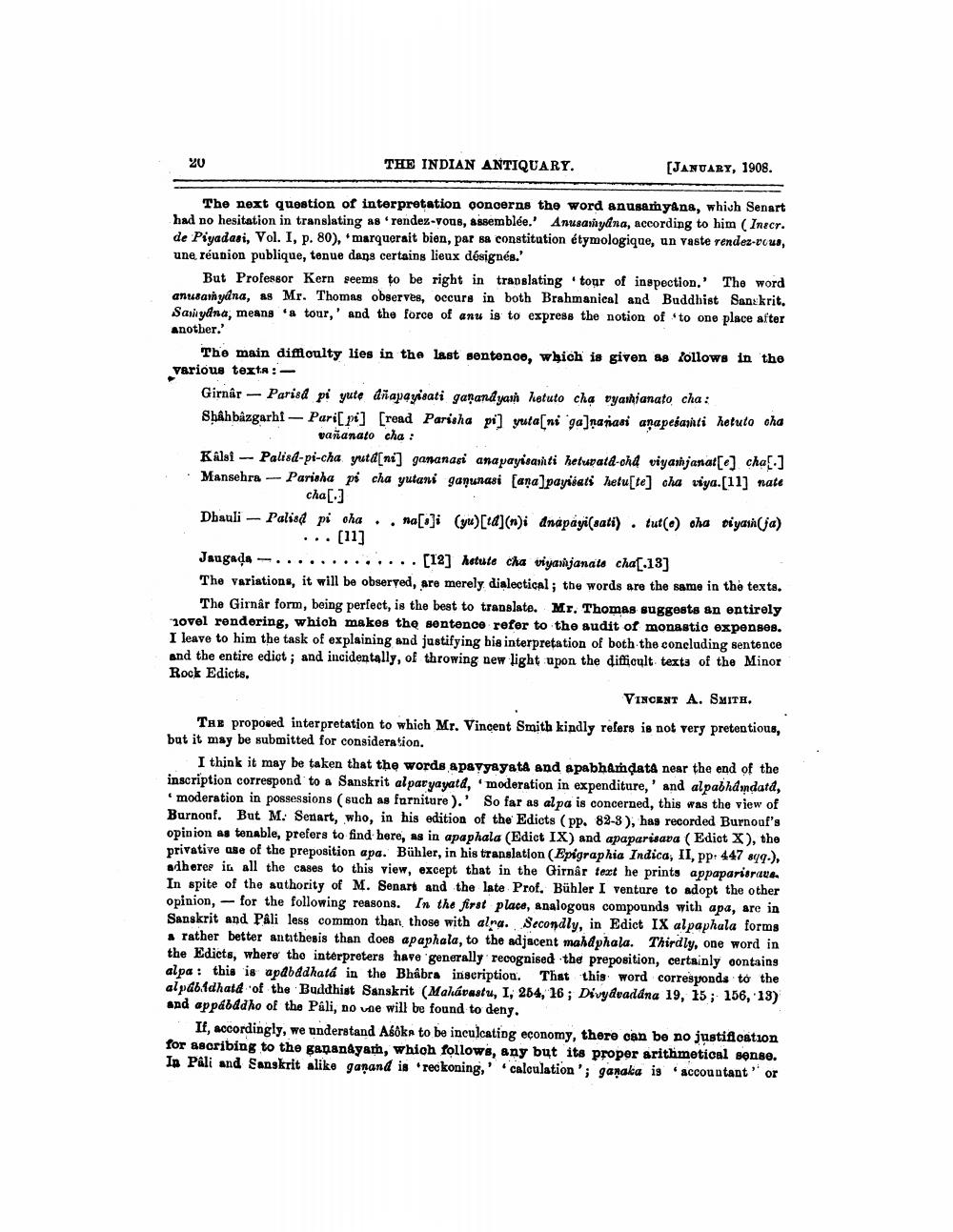

The main difficulty lies in the last sentence, which is given as follows in the various texta :

Girnar

Parisd pi yute dñapayisati ganandyan hetuto cha vyashianato cha: Shahbazgarhi Pari[pi] [read Parisha pi] yuta[ni ga]nanasi anapesanti hetuto cha vañanato cha :

—

Kalsi Palisa-pi-cha yutd[ni] gananasi anapayisanti heturata-cha viyamjanat[e] cha[.] Mansehra Parisha pi cha yutani ganunasi [ana]payisati hetu[te] cha viya.[11] nate cha [.] Dhauli Palisa pi cha

na[]i (yu)[d] (n)i anapayi(sati). tut(e) oha viyan(ja)

[11]

Jaugaḍa

[12] hetute cha viyamjanate cha[13]

The variations, it will be observed, are merely dialectical; the words are the same in the texts. The Girnår form, being perfect, is the best to translate. Mr. Thomas suggests an entirely novel rendering, which makes the sentence refer to the audit of monastic expenses. I leave to him the task of explaining and justifying his interpretation of both the concluding sentence and the entire edict; and incidentally, of throwing new light upon the difficult texts of the Minor Rock Edicts.

VINCENT A. SMITH.

THE proposed interpretation to which Mr. Vincent Smith kindly refers is not very pretentious, but it may be submitted for consideration.

I think it may be taken that the words apavyayata and apabhamdatâ near the end of the inscription correspond to a Sanskrit alparyayata, moderation in expenditure,' and alpabhamdata, " moderation in possessions (such as furniture).' So far as alpa is concerned, this was the view of Burnouf. But M. Senart, who, in his edition of the Edicts (pp. 82-3), has recorded Burnouf's opinion as tenable, prefers to find here, as in apaphala (Edict IX) and apaparisava (Edict X), the privative use of the preposition apa. Bühler, in his translation (Epigraphia Indica, II, pp. 447 sqq.), adheres in all the cases to this view, except that in the Girnâr text he prints appaparierave. In spite of the authority of M. Senart and the late Prof. Bühler I venture to adopt the other opinion, for the following reasons. In the first place, analogous compounds with apa, are in Sanskrit and Pâli less common than those with alra. Secondly, in Edict IX alpaphala forms a rather better antithesis than does apaphala, to the adjacent mahdphala. Thirdly, one word in the Edicts, where the interpreters have generally recognised the preposition, certainly contains alpa: this is apabadhatá in the Bhâbra inscription. That this word corresponds to the alpabidhata of the Buddhist Sanskrit (Mahávastu, I, 254, 16; Divyavadána 19, 15; 156, 13) and appábadho of the Páli, no une will be found to deny.

If, accordingly, we understand Aśoks to be inculcating economy, there can be no justification for ascribing to the gananayam, which follows, any but its proper arithmetical sense. In Pâli and Sanskrit alike ganand is reckoning, calculation'; ganaka is accountant'

or