________________

$ 3]

INDIAN PALEOGRAPHY.

together with the mixed forms Nos. 4, 5, while the numerous inscriptions found further north on the Stūpas of Süñci and Bharahut, in Pabhost and Mathura (pl. II, cols. XVIIIXX) on the coins of Agathocles, and in the Nägärjuni cave (pl. II, col. XVII), offer either pure curved letters or mixed ones. An exception in Mahabodhi-Gaya' is probably explained by the fact that pilgrims from the south incised records of their donations at the famous sanctuary. Similar differences between northern and southern forms may be observed in the case of kha, ja, ma, ra and sa,' and they are all the more important as the circumstances under which the Asoka edicts were incised did not favour the free use of local forms. But the existence of local forms always points to a long continued use of the alphabet in which it is observable.

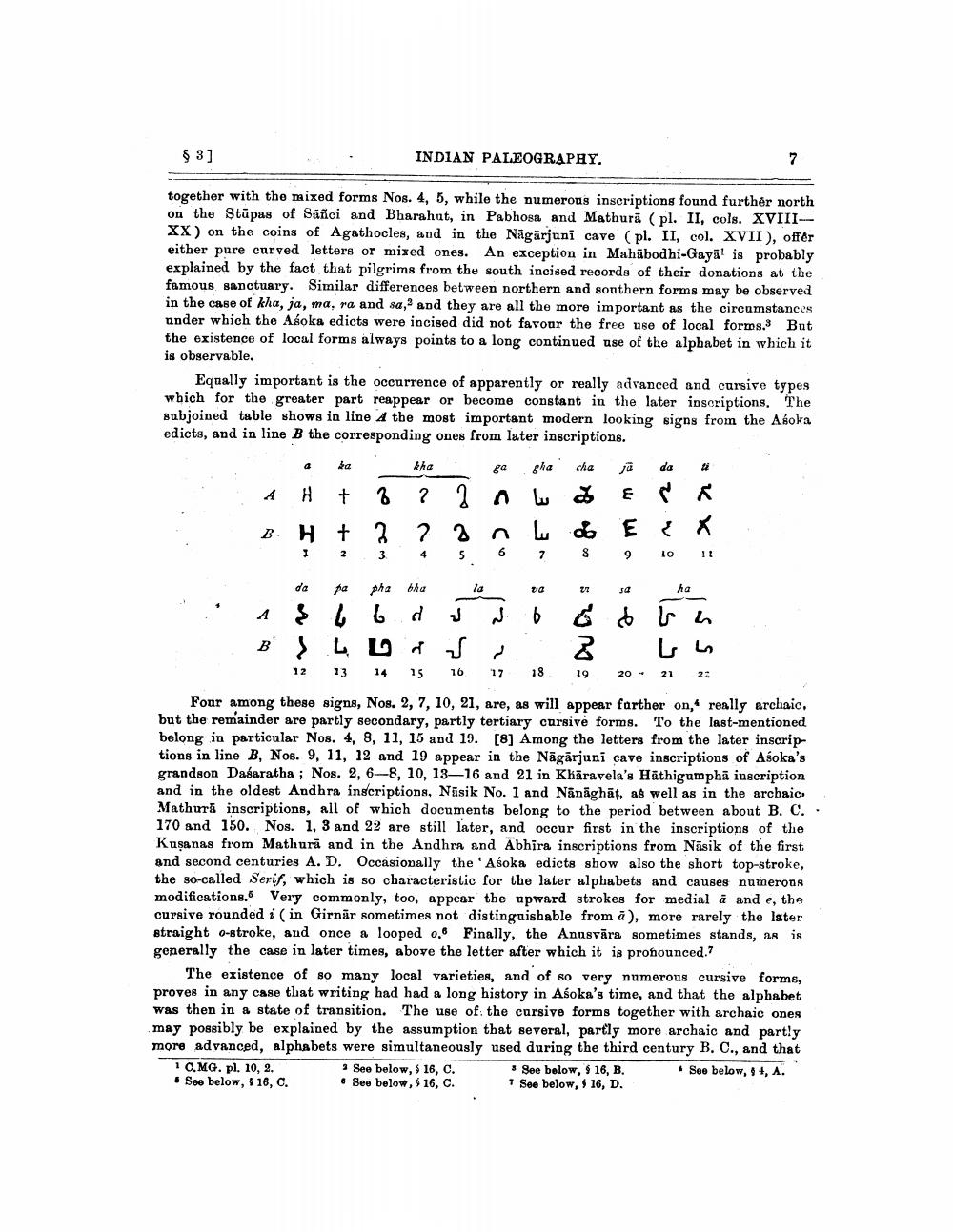

Equally important is the occurrence of apparently or really advanced and cursive types which for the greater part reappear or become constant in the later inscriptions. The subjoined table shows in line A the most important modern looking signs from the Asoka edicts, and in line B the corresponding ones from later inscriptions.

A H + 8 8 w z & rs BH + 7 7 3 n o E X

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 !!

4 : เ เ ส ป

3 6

UOLS

6

6 Ir ,

B

و

با

با

كه

م

ما با

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Foar among these signs, Nos. 2, 7, 10, 21, are, as will appear farther on, really archaic, but the remainder are partly secondary, partly tertiary cursive forms. To the last-mentioned belong in particular Nos. 4, 8, 11, 15 and 19. [8] Among the letters from the later inscriptions in line B, Nos. 9, 11, 12 and 19 appear in the Nāgārjuni cave inscriptions of Asoka's grandson Dasaratha ; Nog. 2, 6-8, 10, 13-16 and 21 in Khāravela's Häthigumphā inscription and in the oldest Andhra inscriptions, Nusik No. 1 and Nānāghāt, as well as in the archaic, Mathurā inscriptions, all of which documents belong to the period between about B. C.. 170 and 150. Nos. 1, 3 and 22 are still later, and occur first in the inscriptions of the Kuşanas from Mathura and in the Andhra and Abhira inscriptions from Näsik of the first and second centuries A. D. Occasionally the 'Asoka edicts show also the short top-stroke, the so-called Serif, which is so characteristic for the later alphabets and causes numerous modifications. Very commonly, too, appear the upward strokes for medial a and e, the cursive rounded i(in Girnär sometimes not distinguishable from a), more rarely the later straight 0-stroke, and once a looped 0,6 Finally, the Anusvāra sometimes stands, as is generally the case in later times, above the letter after which it is pronounced.7

The existence of so many local varieties, and of so very numerous cursive forms, proves in any case that writing had had a long history in Asoka's time, and that the alphabet was then in a state of transition. The use of the cursive forms together with archaic ones may possibly be explained by the assumption that several, partly more archaic and partly more advanced, alphabets were simultaneously used during the third century B. C., and that 1 C.MG. pl. 10, 2.

See below, 616, C. * See below, $ 16, B.

See below, $ 4, A. . See below, 116, C. • See below, 16, C.

See below, 116, D.