________________

88

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY.

[FABRUARY, 1902.

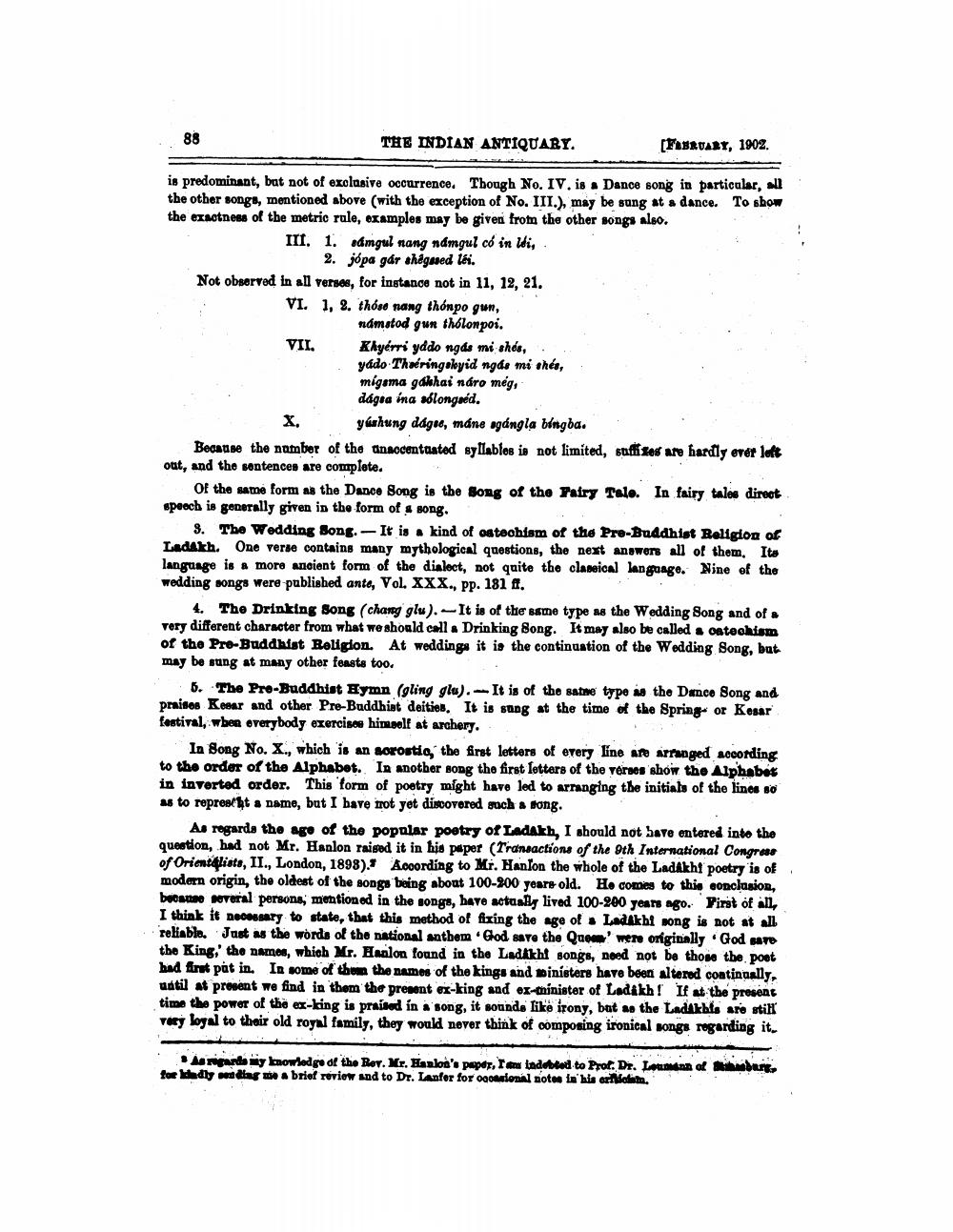

is predominant, but not of exclusive occurrence. Though No. IV.is, Dance song in particular, all the other songs, mentioned above (with the exception of No. III.), may be song at a dance. To show the exactness of the metric rule, examples may be given from the other songs also.

II. 1. tang mang namgel có im đểi, .

2. jópa gar shaganed léi. Not observed in all verses, for instance not in 11, 12, 21.

VI. 1, 2. those nang thónpo gun,

namstod gur thólonpoi. Khyérri yddo ngas mi shos,.. yddo Tharringoloyid ngda mi shes, migoma galhai náro meg, dágra ina sólongaed.

yukung dagro, máne agángla bingba. Because the number of the anaccentuated syllables is not limited, suffses are hardly ever lett out, and the sontences are complete.

of the same form as the Dance Song is the song of the Fairy Tale. In fairy tales direct speech is generally given in the form of song.

9. The Wedding Song. It is a kind of osteohism of the Pre-Buddhist Religion of Ladakh. One verde contains many mythological questions, the next answers all of them. Its language is a more ancient form of the dialect, not quite the classical language. Nine of the wedding songs were published ante, Vol. XXX., pp. 181 ft.

4. The Drinking Song (chang glu). It is of the same type as the Wedding Song and of very different character from what we should call . Drinking Song. It may also be called ontechiam of the Pre-Buddhist Boligon. At weddings it is the continuation of the Wedding Song, but may be sung at many other feasts too.

6. The Pro-Buddhist Hymn (gling glu).-It is of the same type is the Dance Song and prinos Keear and other Pre-Buddhist deities. It is sung at the time of the Spring- or Kosar festival, when overybody exercise himself at archery.

In Song No. X., which is an sorostio, the first letters of every line are arranged according to the order of the Alphabet. In another song the first letters of the verses show the Alphabet in inverted order. This form of poetry might have led to arranging the initials of the lines 80 as to repreacht a name, but I have trot yet discovored much tong.

As regards the age of the popular poetry of Ladakh, I should not have entered into the question, had not Mr. Hanlon raised it in his paper (Transactions of the 9th International Congress of Orientalista, II., London, 1898). According to Mr. Hanlon the whole of the Ladakht poetry is of modern origin, the oldest of the songs being about 100-200 year old. He comes to this conclusion, boonte several persona, mentioned in the songs, have actually lived 100-200 years ago. Yirst of all, I think it necessary to state, that this method of fixing the age of Ladakht song is not at all reliable. Just as the words of the national anthem God save the Queen' were originally God samo the King,' the names, which Mr. Hanlon found in the Ladakht songs, need not be those the poet had Airt pat in. In some of them the names of the kings and winisters have been altered continually, until at present we find in them the present er-king and ex-minister of Ladakh! If at the present time the power of the ex-king is praised in a song, it sounds like irony, but as the Ladakhls are still very loyal to their old royal family, they would never think of composing ironical songs regarding it.

Aangaande my knowledge of the Rev. Mr. Hanlon's paper, au ladotted to Prof. Dr. Let for ledly wondlas me brief review and to Dr. Lanfor for concional note l'his oroit.

of M

ount