________________

JULY, 1897.]

THE MANDUKYA UPANISHAD.

171

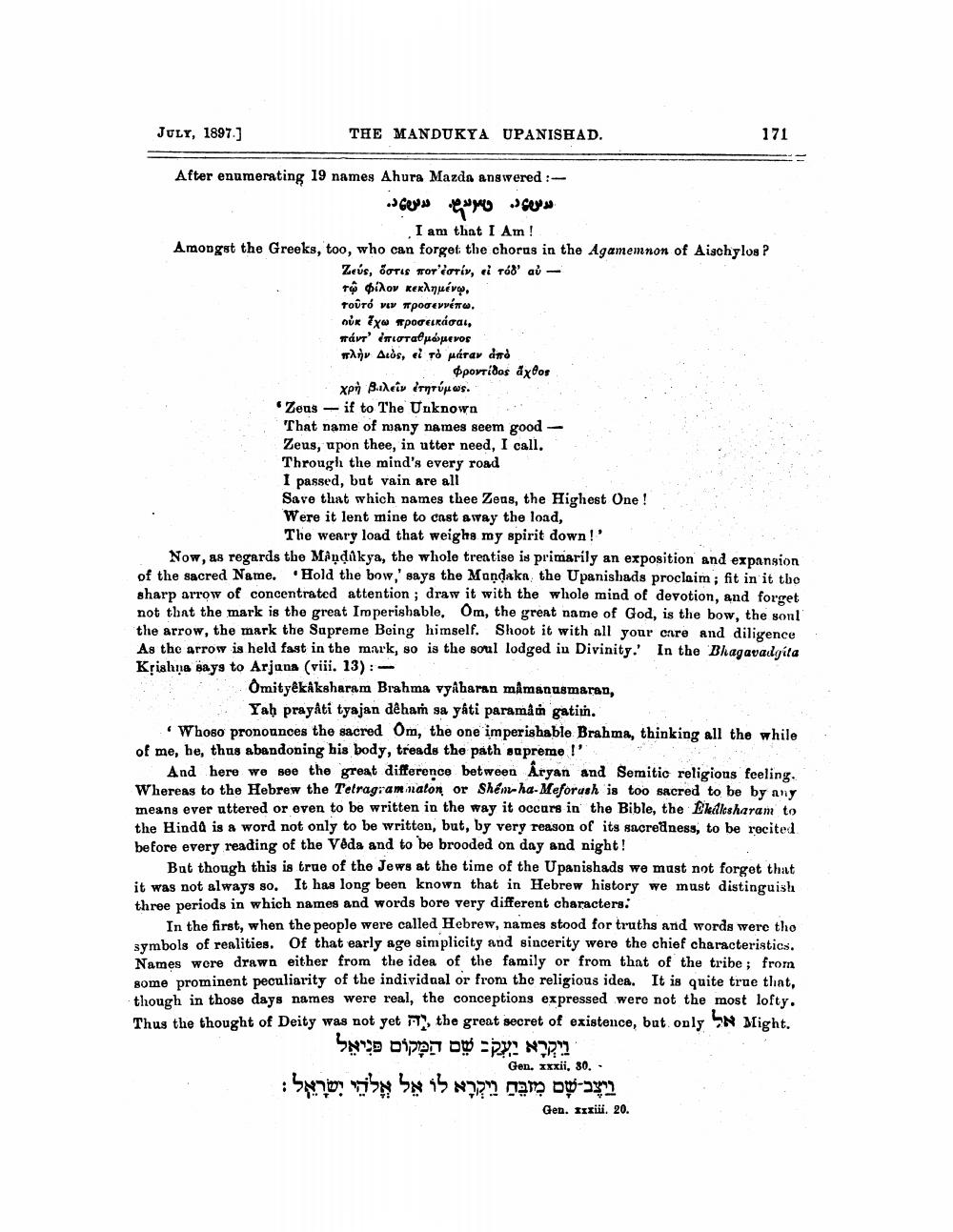

After enumerating 19 names Ahura Mazda answered :

مولاه. دهج د.

دهید.

I am that I Am ! Amongst the Greeks, too, who can forget the chorus in the Agamemnon of Aischylos ?

Zeús, Boris For coriv, ei rád aủ - τω φίλον κεκλημένω, τούτό νιν προσεννέπω, ουκ έχω προσειπάσαι, trávr' (totapeperos πλήν Διός, εί το μάταν από

φροντίδος άχθος χρή βιλείν έτηγύμως. Zeus if to The Unknown That name of many names seem goodZeus, upon thee, in utter need, I call. Through the mind's every road I passed, but vain are all Save that which names thee Zeas, the Highest One! Were it lent mine to cast away the load,

The weary load that weighs my spirit down! Now, as regards the Mândákya, the whole treatise is primarily an exposition and expansion of the sacred Name. Hold the bow,' says the Mandaka the Upanishads proclaim; fit in it tbo sharp arrow of concentrated attention ; draw it with the whole mind of devotion, and forget not that the mark is the great Imperishable, Om, the great name of God, is the bow, the sonl the arrow, the mark the Supreme Being himself. Shoot it with all your enre and diligence As the arrow is held fast in the mark, so is the soul lodged in Divinity. In the Bhagavadgita Krishna says to Arjana (viii. 13): -

OmityêkAksharam Brahma vyharan mamanusmaran,

Yah prayati tyajan dêham sa yâti paramåón gatin. Whoso pronounces the sacred Om, the one imperishable Brahma, thinking all the while of me, be, thus abandoning his body, treads the path sapremo !

And here we see the great difference between Aryan and Semitic religions feeling, Whereas to the Hebrew the Tetragram naton or Shém-ha-Meforush is too sacred to be by any means ever attered or even to be written in the way it occurs in the Bible, the Eldlesharam to the Hindå is a word not only to be written, but, by very reason of its sacredness, to be rocited before every reading of the Veda and to be brooded on day and night!

But though this is true of the Jews at the time of the Upanishads we must not forget that it was not always so. It has long been known that in Hebrew history we must distinguish three periods in which names and words bore very different characters:

In the first, when the people were called Hebrew, names stood for truths and words were tho symbols of realities. Of that early age simplicity and sincerity were the chief characteristics. Names were drawn either from the idea of the family or from that of the tribe ; from some prominent peculiarity of the individual or from the religious idea. It is quite true that, though in those days names were real, the conceptions expressed were not the most lofty. Thus the thought of Deity was not yet ry, the great secret of existence, but only 5N Might.

וַיִּקְרָא יַעֲקֹב שֵׁם הַמָּקוֹם פּנִיאֵל וִיצֶב שָׁם מִזְבֵּחַ וַיִּקְרָא לוֹ אֵל אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאל :

Gen. xxxii, 30.

Gen. Ixxiii. 20.