________________

APRIL, 1992.

BOOK-NOTICES.

127

asi

in

rúl

Son

ti

Weep

Head

Seed High asang Sit

t' House

Slave

shal (shil) Inside

sun Snake Iron tir

afa Luoking-glass kla-lung Stone lung Make

Sweet aklum Many

tam (tim) Thatch Near

anui This Necklace

Tooth ha Nose ngã

tap Old

ali Well (be) dan Pumpkin mai Which koi Rain

ruu shuur Widow nu-mè Reap

Wish dū Red

shen Yellow eng Ripe

min You nangma See

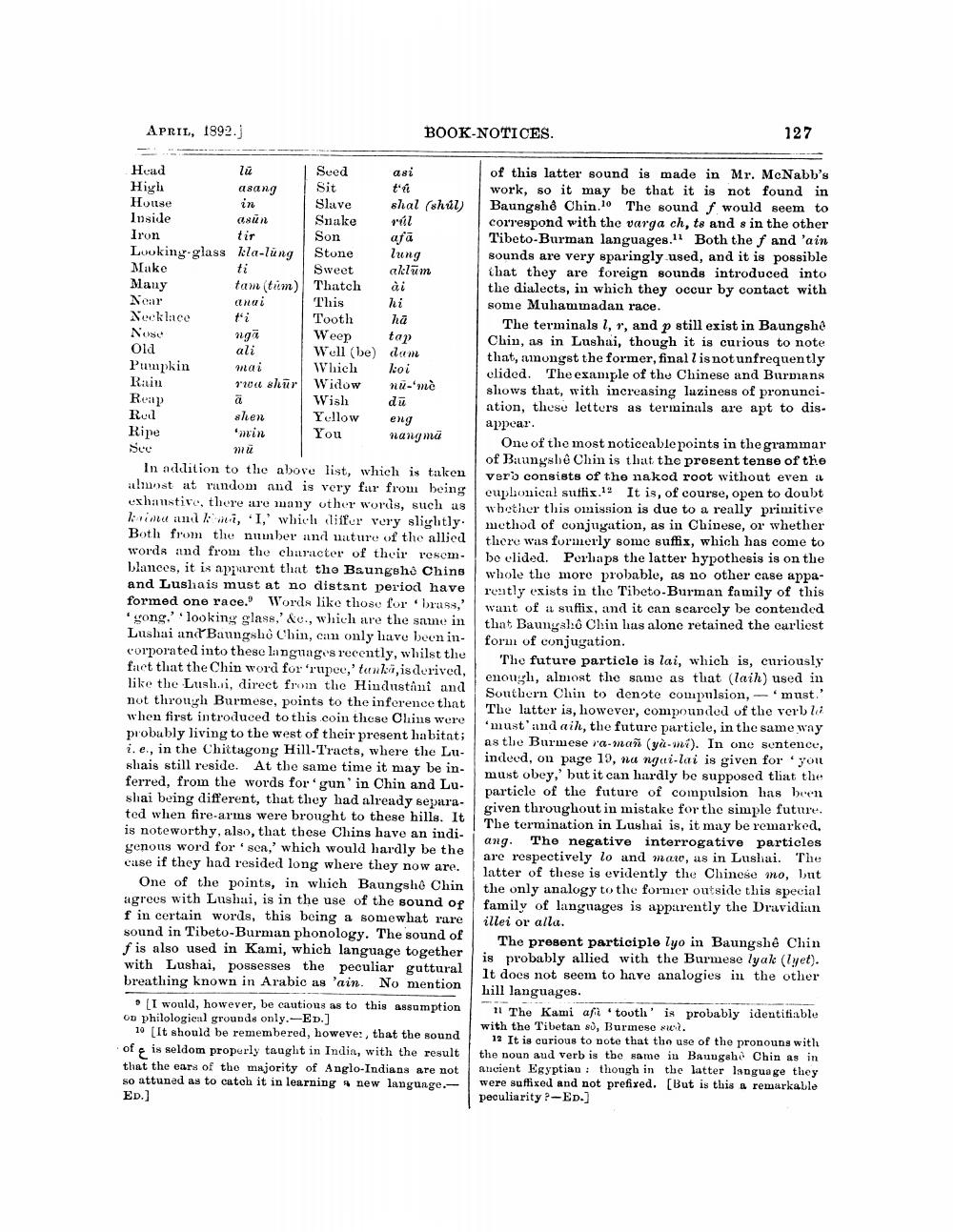

mü In addition to the above list, which is taken

unat at random and is very far from being exhaustive, there are many other words, such as Trimu ani kwei, I, which cliffer very slightly. Both from the number and nature of the allied words and from the character of their resom. Wances, it is apparent that the Baungshe Chins and Lushais must at no distant period have formed one race. Words like those for brass, gong,' looking glass,' &c., which are the same in Lushai and Baungsho Chin, can only have been in. corporated into these languages recently, whilst the fact that the Chin word for 'rupee,' tanki,is derived, like the Lushi, direct from the Hindustani and not through Burmese, points to the inference that when first introduced to this coin these Chins were probably living to the west of their present habitat; i.e., in the Chittagong Hill-Tracts, where the Luslais still reside. At the same time it may be in- ferred, from the words for gun' in Chin and Lu. sliai being different, that they had already separated when fire arms were brought to these hills. It is noteworthy, also, that these Chins have an indi. genons word for 'sea,' which would hardly be the cuse if they had resided long where they now are.

One of the points, in which Baungsho Chin agrees with Lushui, is in the use of the sound of f in certain words, this being a somewhat rare sound in Tibeto-Burman phonology. The sound of f is also used in Kami, which language together with Lushai, possesses the peculiar guttural breathing known in Arabic as 'ain. No mention

(I would, however, be cautious as to this assumption on philological grounds only.-ED.]

10 [It should be remembered, however, that the sound of is seldom properly taught in India, with the result that the ears of the majority of Anglo-Indians are not so attuned as to catch it in learning new langunge.ED.)

of this latter sound is made in Mr. McNabb's work, so it may be that it is not found in Baungshỏ Chin. The sound f would seem to correspond with the varga ch, ts and s in the other Tibeto-Burman languages. Both the f and 'ain sounds are very sparingly used, and it is possible that they are foreign sounds introduced into the dialects, in which they occur by contact with some Muhammadan race.

The terminals 1,r, and p still exist in Baungah Chin, as in Lushai, though it is curious to note that, amongst the former, finall is not unfrequently clided. The example of the Chinese and Burmans shows that, with increasing laziness of pronunci. ation, these letters as terminals are apt to disappear.

One of the most noticeable points in the grammar of Bauungsho Chin is that the present tense of the vers consists of the nakod root without even i euphonical sutis. It is, of course, open to doubt whether this omission is due to a really primitive method of conjugation, as in Chinese, or whether there was formerly some suffix, which has come to bo olided. Perhaps the latter hypothesis is on the whole the more probable, as no other case appareatly exists in the Tibeto-Burman family of this want of a suflis, and it can scarcely be contended that Baungal: Chin las alone retained the earliest form of conjugation.

The future particle is lai, which is, curiously enough, almost the same as that (lail) used in Southern Chin to denote compulsion, 'must.' The latter is, however, compounded of the verb lii must'andail, the future particle, in the same way as the Burmese ra-mañ (yu-mi). In one sentence', indeod, on page 19, na ngai-lai is given for you must obey.' but it can hardly be supposed tliat the particle of the future of compulsion has been given throughout in mistake for the simple future. The termination in Lushai is, it may be remarked, ang. The negative interrogative particles are respectively lo and mate, as in Lushai. The latter of these is evidently the Chinese mo, but the only analogy to the former outside this special family of languages is apparently the Dravidian illei or alla.

The present participle lyo in Baungshê Chin is probably allied with the Burmese lyal (lyet). It does not seem to have analogies in the other hill languages.

11 The Kami afi 'tooth' is probably identifiable with the Tibetan 80, Burmese .

12 It is curious to note that the use of the pronouns with the noun and verb is the same in Banugahó Chin as in Ancient Egyptian : though in the latter language they were suffixed and not prefixed. (But is this a remarkable peculiarity ?-ED.)