________________

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY.

(MARCH, 1889.

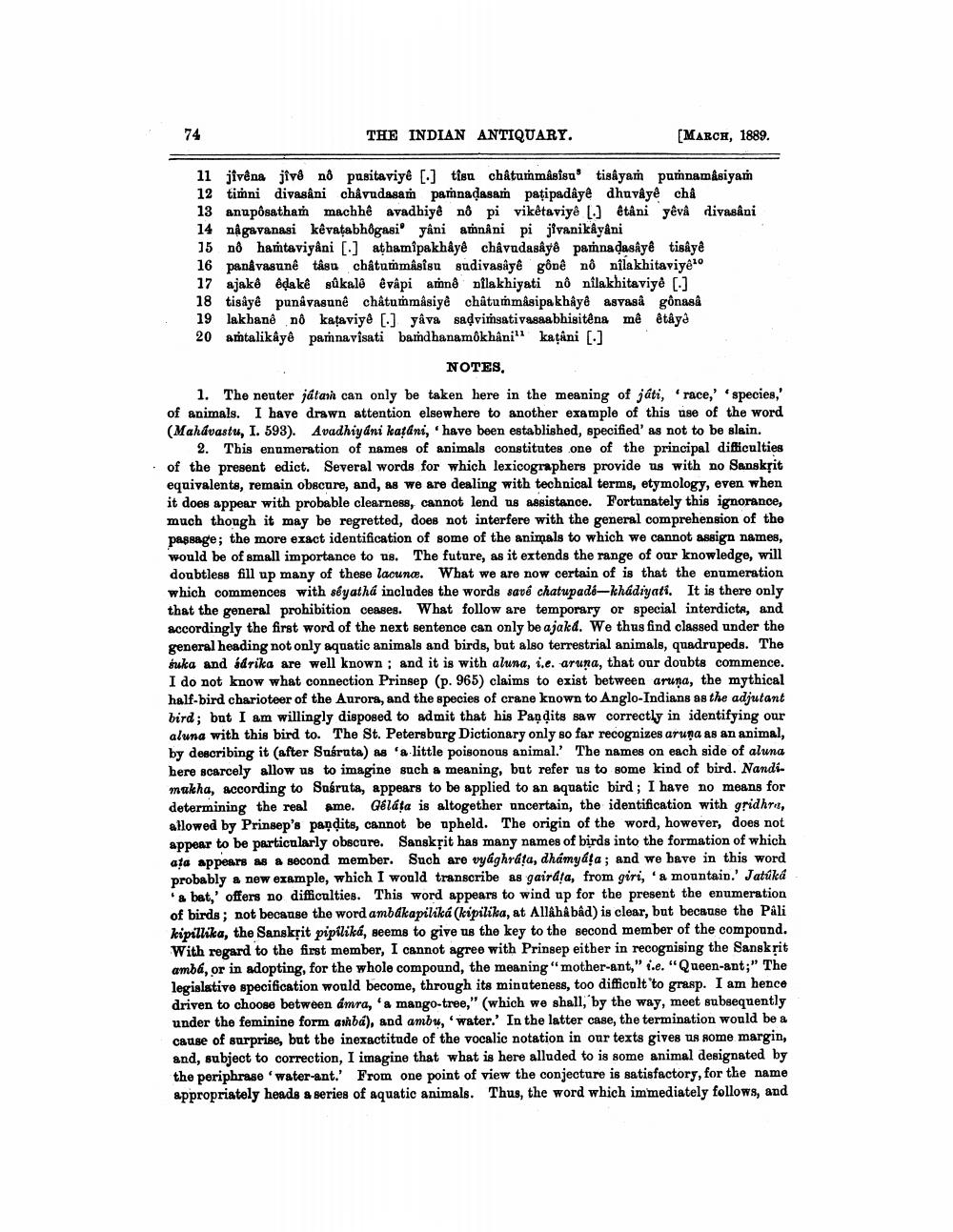

11 jivêna jîvê nô pasitaviye [.] tisu châturmâsisa' tisayam punamasiyam 12 tinni divagini charudasa pannadasai petipadâye dhavâye chỉ 13 anuposatham machhê avadhiyê nô pi vikêtaviyê (.] @táni yêvå divasani 14 nagavanasi kêvatabhôgasi' yani amnâni pi jlvanikayani 15 nð hamtaviyani [] athamipakhûyê châvudasayé pamna dasayé tiskye 16 panvas nê tân chất mâyfan gadivasảyê gônề nô nilakhitaviyeko 17 ajakê địa kê Bakalô & vấpi anô nflakhiyati nô nilakhitaviye [-] 18 tisayé punávasune châtummâsiye châtummasipa khay& asvasa gônasa 19 lakbanê nð kațaviye [.] yâva sadvimsativasaabhisitenamê étaya 20 amtalikâyê pamnavisati bamdhanamokhâni" katani (2)

NOTES 1. The nenter játar can only be taken here in the meaning of játi, race,' species,' of animals. I have drawn attention elsewhere to another example of this use of the word (Mahávastu, I. 593). Avadhiyáni kațâni, 'have been established, specified' as not to be slain.

2. This enumeration of names of animals constitutes one of the principal difficulties • of the present edict. Several words for which lexicographers provide us with no Sanskțit

equivalents, remain obscure, and, as we are dealing with technical terms, etymology, even when it does appear with probable clearness, cannot lend us assistance. Fortunately this ignorance, much though it may be regretted, does not interfere with the general comprehension of the passage; the more exact identification of some of the animals to which we cannot assign names, would be of small importance to us. The future, as it extends the range of our knowledge, will

doubtless fill up many of these lacune. What we are now certain of is that the enumeration which commences with s@yathá includes the words savé chatupadó-khadiyati. It is there only that the general prohibition ceases. What follow are temporary or special interdicta, and accordingly the first word of the next sentence can only be ajakd. We thus find classed under the general heading not only aquatic animals and birds, but also terrestrial animals, quadrupeds. The suka and ádrika are well known; and it is with aluna, i.e. aruna, that our doubts commence. I do not know what connection Prinsep (p. 965) claims to exist between aruna, the mythical half-bird charioteer of the Aurora, and the species of crane known to Anglo-Indians as the adjutant bird; but I am willingly disposed to admit that his Pandits saw correctly in identifying our aluna with this bird to. The St. Petersburg Dictionary only so far recognizes aruna as an animal, by describing it (after Suśruta) as a little poisonous animal.' The names on each side of aluna here scarcely allow us to imagine such a meaning, but refer us to some kind of bird. Nandimakha, according to Susruta, appears to be applied to an aquatic bird; I have no means for determining the real ame. Géláta is altogether uncertain, the identification with gridhta, allowed by Prinsep's pandits, cannot be upheld. The origin of the word, however, does not appear to be particularly obscure. Sanskțit has many names of birds into the formation of which ata appears as a second member. Such are vyághráta, dhámyata ; and we have in this word probably a new example, which I would transcribe as gairdta, from giri, a mountain.' Jatúká

& bat,' offers no difficulties. This word appears to wind up for the present the enumeration of birds; not because the word ambákapiliká (kipilika, at Allahabad) is clear, but because the Påli kipillika, the Sanskrit pipiliká, seems to give us the key to the second member of the compound. With regard to the first member, I cannot agree with Prinsep either in recognising the Sanskrit amba, or in adopting, for the whole compound, the meaning "mother-ant," i.e. "Queen-ant;" The legislative specification would become, through its minuteness, too difficult to grasp. I am hence driven to choose between amra, 'a mango-tree," (which we shall,' by the way, meet subsequently under the feminine form ashba), and ambu, 'water.' In the latter case, the termination would be a cause of surprise, but the inexactitude of the vocalic notation in our texts gives us some margin, and, subject to correction, I imagine that what is here alluded to is some animal designated by the periphrase 'water-ant.' From one point of view the conjecture is satisfactory, for the name appropriately heads a series of aquatic animals. Thus, the word which immediately follows, and