________________

184

distinguish roots by tonal inflexion, diminish; as in Khyen and Burmese.

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY.

3. Phaloung and Talaing have developed, besides the usual finals, also k, h, r, rh, l, lh; the initials are very numerous; the tonal system has been discarded-because the language possessed in its consonants and simple a-tonal vowels sufficient means of differentiation of roots.

4. Where final consonants have been partly or wholly disposed of (as in the Mandarin and Sgō Karen), vowel-accidents (tone, pitch of voice, emphasis) and initial consonants increase correspondingly.

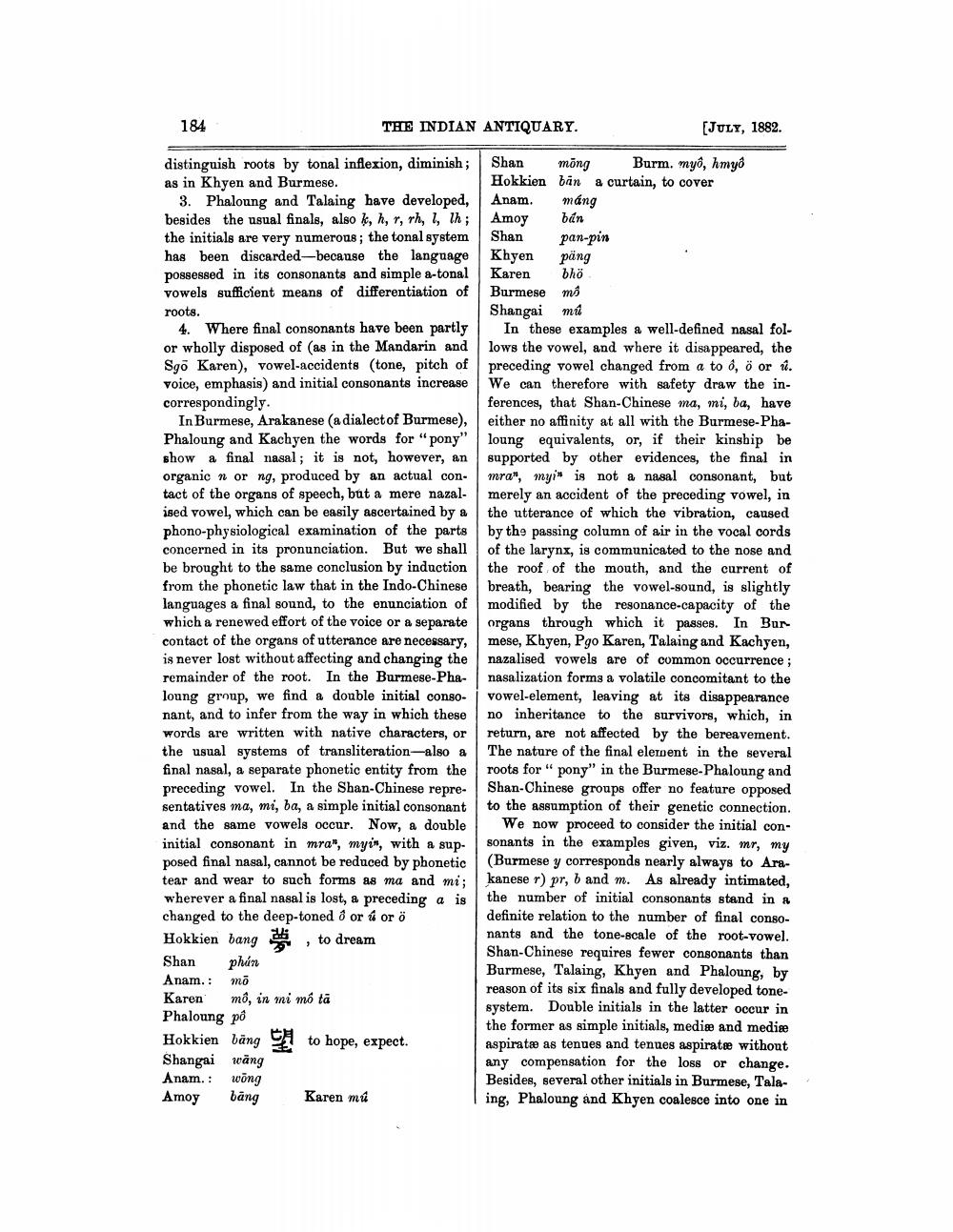

In Burmese, Arakanese (a dialect of Burmese), Phaloung and Kachyen the words for "pony" show a final nasal; it is not, however, an organic nor ng, produced by an actual contact of the organs of speech, but a mere nazalised vowel, which can be easily ascertained by a phono-physiological examination of the parts concerned in its pronunciation. But we shall be brought to the same conclusion by induction from the phonetic law that in the Indo-Chinese languages a final sound, to the enunciation of which a renewed effort of the voice or a separate contact of the organs of utterance are necessary, is never lost without affecting and changing the remainder of the root. In the Burmese-Phaloung group, we find a double initial consonant, and to infer from the way in which these words are written with native characters, or the usual systems of transliteration-also a final nasal, a separate phonetic entity from the preceding vowel. In the Shan-Chinese representatives ma, mi, ba, a simple initial consonant and the same vowels occur. Now, a double initial consonant in mra", myin, with a supposed final nasal, cannot be reduced by phonetic tear and wear to such forms as ma and mi; wherever a final nasal is lost, a preceding a is changed to the deep-toned ô or ú or ö

Hokkien bang, to dream

Shan

phún Anam. : mō

Karen mộ, in mẻ mô tả

Phaloung po

Hokkien bäng to hope, expect.

Shangai wäng Anam. wong Amoy bang

Karen mú

[JULY, 1882.

Shan mōng Burm. myô, hmyo Hokkien ban a curtain, to cover

Anam.

Amoy

Shan pan-pin Khyen päng Karen bhö Burmese mo Shangai

mú

In these examples a well-defined nasal follows the vowel, and where it disappeared, the preceding vowel changed from a to o, ö or û. We can therefore with safety draw the inferences, that Shan-Chinese ma, mi, ba, have either no affinity at all with the Burmese-Phaloung equivalents, or, if their kinship be supported by other evidences, the final in mra", myi" is not a nasal consonant, but merely an accident of the preceding vowel, in the utterance of which the vibration, caused by the passing column of air in the vocal cords of the larynx, is communicated to the nose and the roof of the mouth, and the current of breath, bearing the vowel-sound, is slightly modified by the resonance-capacity of the organs through which it passes. In Burmese, Khyen, Pgo Karen, Talaing and Kachyen, nazalised vowels are of common occurrence; nasalization forms a volatile concomitant to the vowel-element, leaving at its disappearance no inheritance to the survivors, which, in return, are not affected by the bereavement. The nature of the final element in the several roots for "pony" in the Burmese-Phaloung and Shan-Chinese groups offer no feature opposed to the assumption of their genetic connection.

We now proceed to consider the initial consonants in the examples given, viz. mr, my (Burmese y corresponds nearly always to Arakanese r) pr, b and m. As already intimated, the number of initial consonants stand in a definite relation to the number of final consonants and the tone-scale of the root-vowel. Shan-Chinese requires fewer consonants than Burmese, Talaing, Khyen and Phaloung, by reason of its six finals and fully developed tonesystem. Double initials in the latter occur in the former as simple initials, media and media aspirate as tenues and tenues aspirate without any compensation for the loss or change. Besides, several other initials in Burmese, Talaing, Phaloung and Khyen coalesce into one in

máng

bán