________________

CHAPTER 19)

SOUTH INDIA

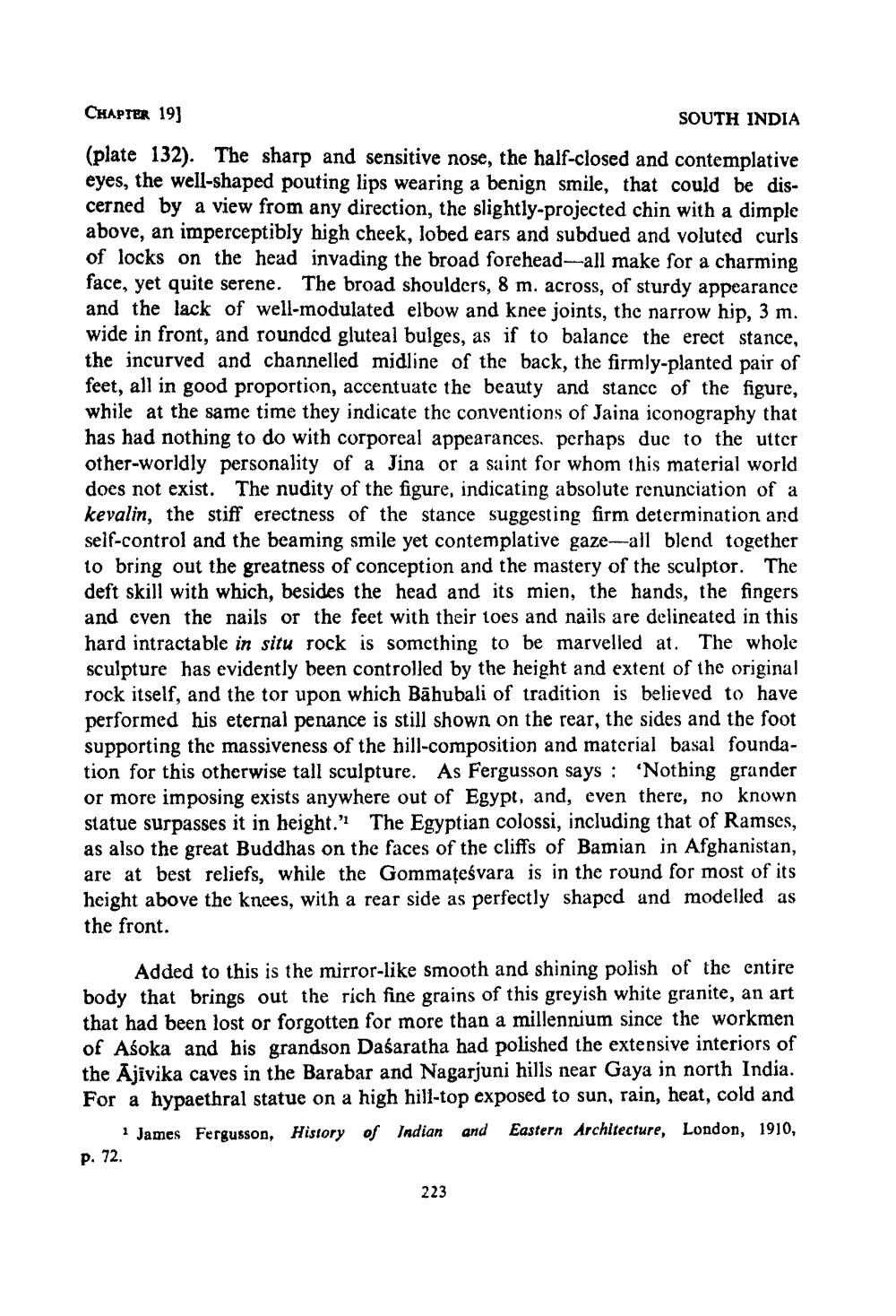

(plate 132). The sharp and sensitive nose, the half-closed and contemplative eyes, the well-shaped pouting lips wearing a benign smile, that could be discerned by a view from any direction, the slightly-projected chin with a dimple above, an imperceptibly high cheek, lobed ears and subdued and voluted curls of locks on the head invading the broad forehead--all make for a charming face, yet quite serene. The broad shoulders, 8 m. across, of sturdy appearance and the lack of well-modulated elbow and knee joints, the narrow hip, 3 m. wide in front, and rounded gluteal bulges, as if to balance the erect stance, the incurved and channelled midline of the back, the firmly-planted pair of feet, all in good proportion, accentuate the beauty and stance of the figure, while at the same time they indicate the conventions of Jaina iconography that has had nothing to do with corporeal appearances. perhaps due to the utter other-worldly personality of a Jina or a saint for whom this material world does not exist. The nudity of the figure, indicating absolute renunciation of a kevalin, the stiff erectness of the stance suggesting firm determination and self-control and the beaming smile yet contemplative gaze--all blend together to bring out the greatness of conception and the mastery of the sculptor. The deft skill with which, besides the head and its mien, the hands, the fingers and cven the nails or the feet with their toes and nails are delineated in this hard intractable in situ rock is something to be marvelled at. The whole sculpture has evidently been controlled by the height and extent of the original rock itself, and the tor upon which Bahubali of tradition is believed to have performed his eternal penance is still shown on the rear, the sides and the foot supporting the massiveness of the hill-composition and material basal foundation for this otherwise tall sculpture. As Fergusson says : 'Nothing grander or more imposing exists anywhere out of Egypt, and, even there, no known statue surpasses it in height.' The Egyptian colossi, including that of Ramses, as also the great Buddhas on the faces of the cliffs of Bamian in Afghanistan, are at best reliefs, while the Gommateśvara is in the round for most of its height above the knees, with a rear side as perfectly shaped and modelled as the front.

Added to this is the mirror-like smooth and shining polish of the entire body that brings out the rich fine grains of this greyish white granite, an art that had been lost or forgotten for more than a millennium since the workmen of Asoka and his grandson Dasaratha had polished the extensive interiors of the Ajivika caves in the Barabar and Nagarjuni hills near Gaya in north India. For a hypaethral statue on a high hill-top exposed to sun, rain, heat, cold and

James Fergusson, History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, London, 1910, p. 72.

223