________________

10

NYAYAVATARA.

having repeatedly seen in the kitchen and other places, that where there is smoke there is fire, and having realised in his mind that there is a universal antecedence of fire in respect of smoke, a man afterwards goes to a hill and entertains a doubt as to whether or not there is fire in it. Instantly, when he observes smoke on it, he recollects the inseparablo connection between fire and smoke, and concludes in his mind that the hill has fire in it, as it bas smokeon it. This is an inference for one's own self. The inference for tho sake of others will be defined later on.

This definition of inforence, says the commentator, sets aside the view of certain writers (such as Dharmakirti, the Buddhist] who maintain that non-perception (anipulahdhi), identity (sverbhava) and causality (karua) are tho marks or grounds of inference, or of certain other writers who hold the effect (kcírya), cause (kiiru?a), conjunction (sainyoga), coexistence (samavaya), and opposition (virodha) to be such marks or grounds. The division of inference as (1) à priori (purvavat, from cause to effect), (2) à posteriori (śeşavat, from effect to cause) and (3) from analogy (saminya to-drsta, perception of homogeneousness, that is, the recognition of the subject as being referrable to some class, and as being thence liable to have predicated of it whatever may be predicable of the class) fas given in the Nyâya-sûtra of Aksapada Gautama) is also hereby set aside.

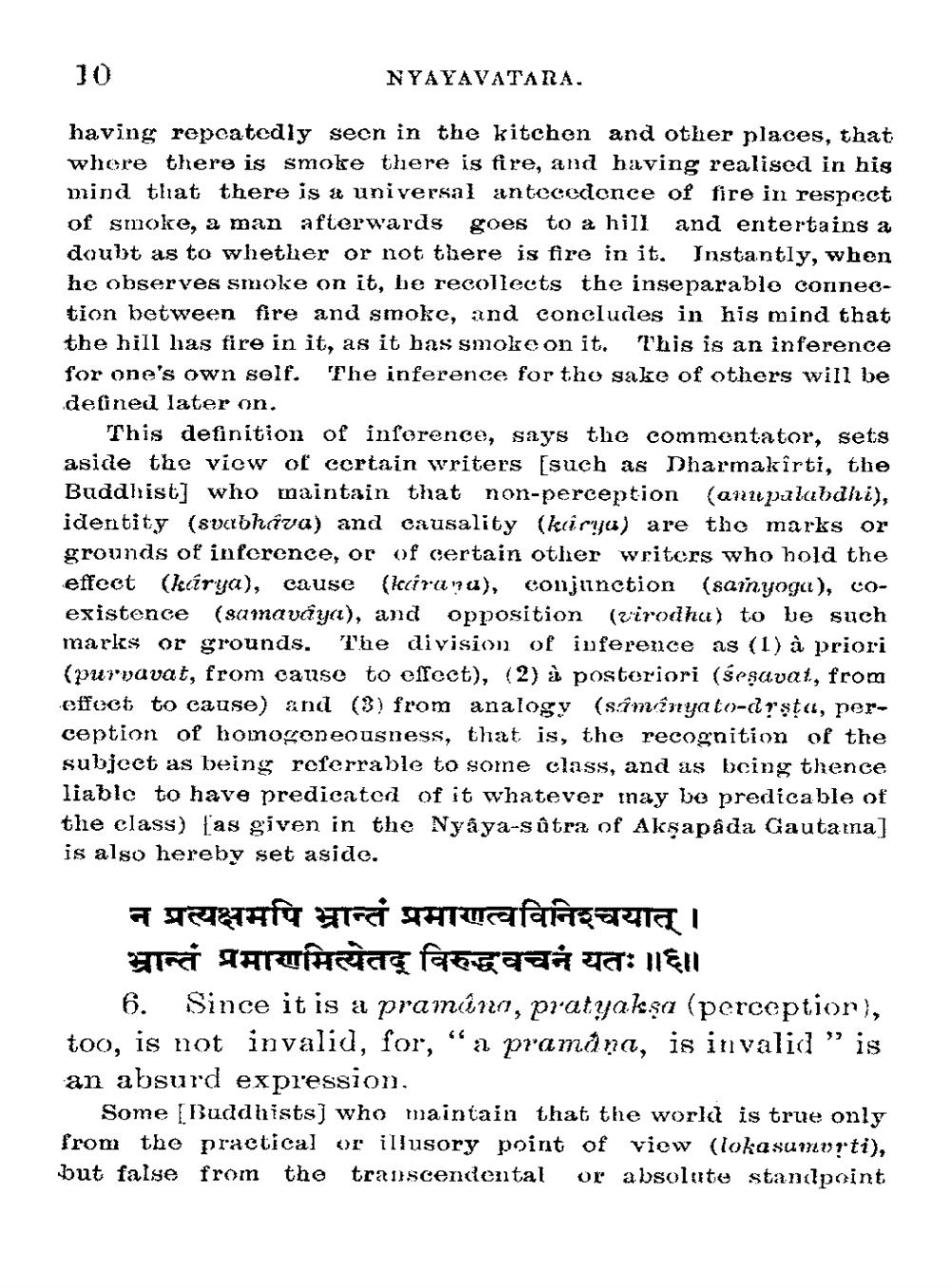

न प्रत्यक्षमपि भ्रान्तं प्रमाणत्वविनिश्चयात् । भ्रान्तं प्रमाणमित्येतद् विरुद्धवचनं यतः॥६॥

6. Since it is a prameno, pratyakşa (perception), too, is not invalid, for, “a pramana, is invalid ” is an absurd expression.

Some Buddhists) who maintain that the world is true only from the practical or illusory point of view (lokasumurti), but false from the transcendental or absolute standpoint