________________

IN THE BOMBAY CIRCLE.

17

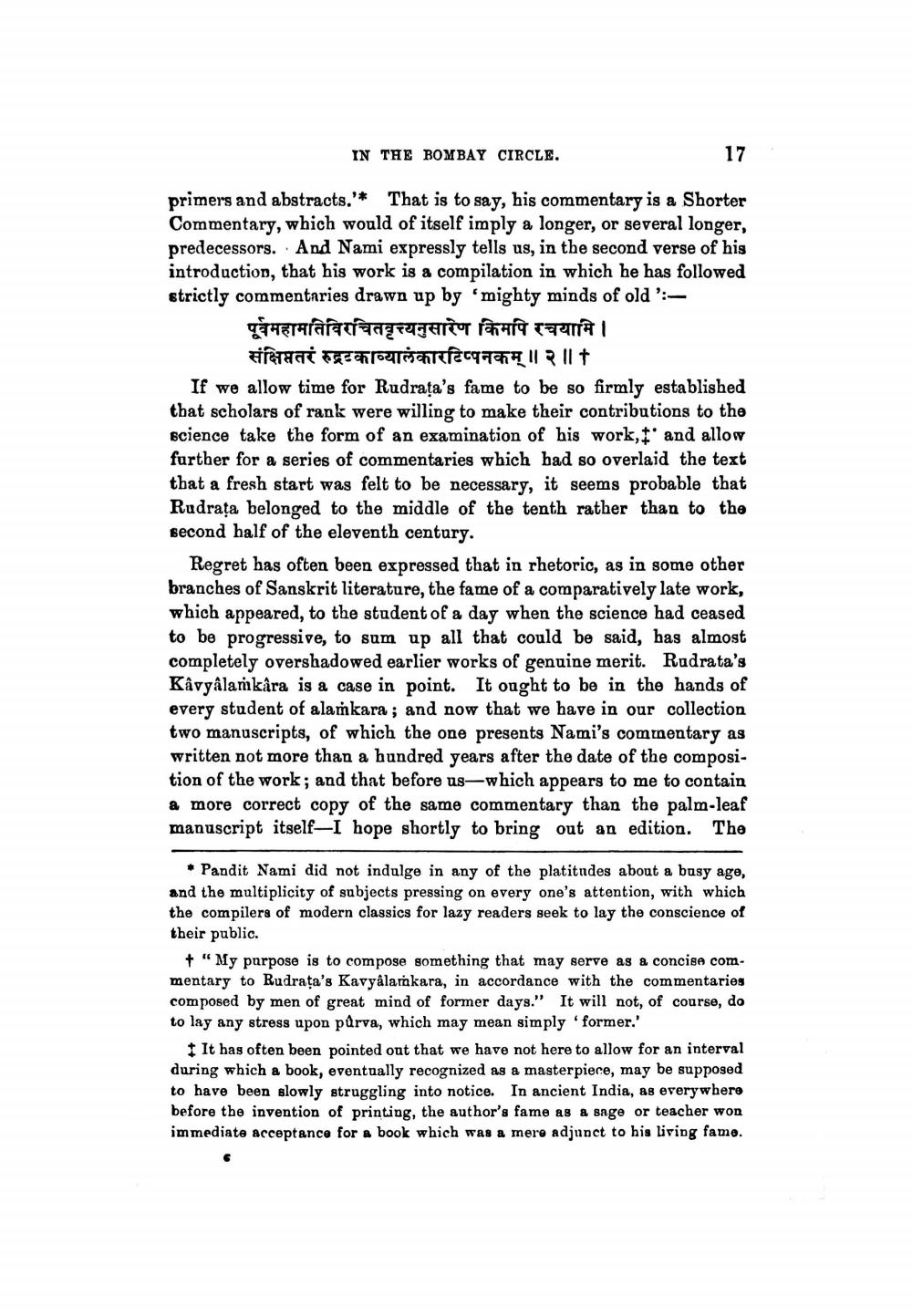

primers and abstracts.'* That is to say, his commentary is a Shorter Commentary, which would of itself imply a longer, or several longer, predecessors. And Nami expressly tells us, in the second verse of his introduction, that his work is a compilation in which he has followed strictly commentaries drawn up by 'mighty minds of old ':

पूर्वमहामतिविरचितवृत्त्यनुसारेण किमपि रचयामि ।

संक्षिप्ततरं रुद्रटकाव्यालंकारटिप्पनकम् ।।२। If we allow time for Rudrata's fame to be so firmly established that scholars of rank were willing to make their contributions to the science take the form of an examination of his work, I. and allow further for a series of commentaries which had so overlaid the text that a fresh start was felt to be necessary, it seems probable that Rudrata belonged to the middle of the tenth rather than to the second half of the eleventh century.

Regret has often been expressed that in rhetoric, as in some other branches of Sanskrit literature, the fame of a comparatively late work, which appeared, to the student of a day when the science had ceased to be progressive, to sum up all that could be said, has almost completely overshadowed earlier works of genuine merit. Radrata's Kavgalankára is a case in point. It ought to be in the hands of every student of alamkara ; and now that we have in our collection two manuscripts, of which the one presents Nami's commentary as written not more than a hundred years after the date of the composition of the work; and that before us—which appears to me to contain a more correct copy of the same commentary than the palm-leaf manuscript itself-I hope shortly to bring out an edition. The

* Pandit Nami did not indulge in any of the platitudes about a busy age, and the multiplicity of subjects pressing on every one's attention, with which the compilers of modern classics for lazy readers seek to lay the conscience of their public.

+ "My purpose is to compose something that may serve as a concise commentary to Rudrata's Kavyalarakara, in accordance with the commentaries composed by men of great mind of former days." It will not, of course, do to lay any stress upon purva, which may mean simply former.'

It has often been pointed out that we have not here to allow for an interval during which a book, eventually recognized as a masterpiece, may be supposed to have been slowly struggling into notice. In ancient India, as everywhere before the invention of printing, the author's fame as a sage or teacher won immediate acceptance for a book which was a mere adjunct to his living fame.