________________

360 :: 4*HICT-HARAT

The attraction of Mookmaatee lies partly in the poet's bit, puns and reversals, and partly in the freedom gained by a renunciation of conventional mater and rhyme. He assigns new meaning to fragments of words in a pseudo-etymological way. Internal rhymes, which sometimes appear somewhat forced and expedient, are delightful nonetheless. Reversals reveal great truths. If you want to be a raahee (a way-farer on the spiritual path), you must become a heera (a diamond). The word svapn (dream) is split and redefined : sva is one's own,pis paalan or maintenance, and nis no. A creature lost in dreams, therefore, cannot maintain itself. Yes, etymology is reinvented. At times, the urge to use multiple rhymes compels the poet to stretch the meanings in an oddly appropriate way.

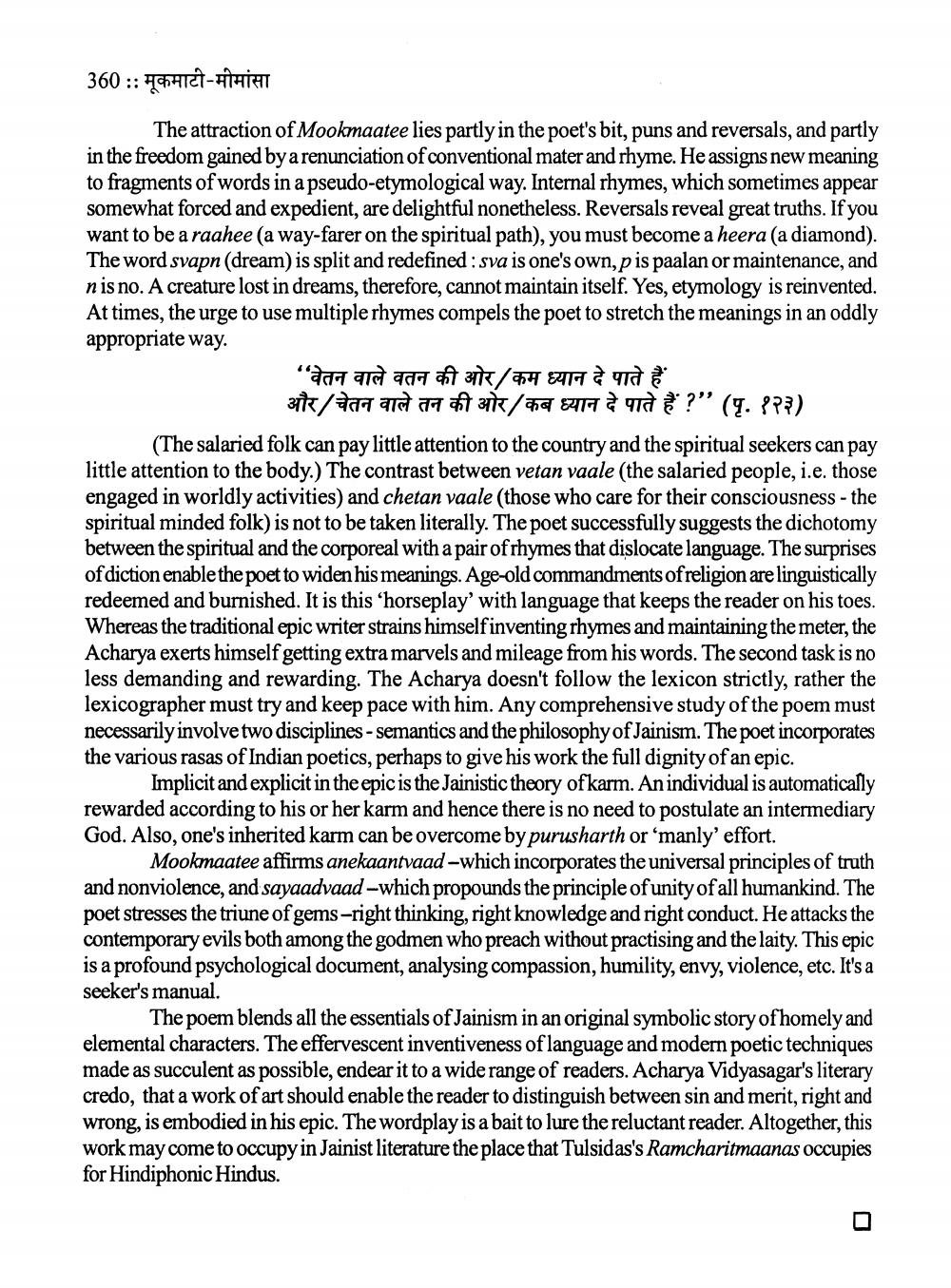

“वेतन वाले वतन की ओर/कम ध्यान दे पाते हैं

31/7 and 317/74 8419 and ?” (q. ???) (The salaried folk can pay little attention to the country and the spiritual seekers can pay little attention to the body.) The contrast between vetan vaale (the salaried people, i.e. those engaged in worldly activities, and chetan vaale (those who care for their consciousness - the spiritual minded folk) is not to be taken literally. The poet successfully suggests the dichotomy between the spiritual and the corporeal with a pair of rhymes that dislocate language. The surprises of diction enable the poet to widen his meanings. Age-old commandments of religion are linguistically redeemed and burnished. It is this ‘horseplay' with language that keeps the reader on his toes. Whereas the traditional epic writer strains himselfinventing rhymes and maintaining the meter, the Acharya exerts himself getting extra marvels and mileage from his words. The second task is no less demanding and rewarding. The Acharya doesn't follow the lexicon strictly, rather the lexicographer must try and keep pace with him. Any comprehensive study of the poem must necessarily involve two disciplines - semantics and the philosophy of Jainism. The poet incorporates the various rasas of Indian poetics, perhaps to give his work the full dignity of an epic.

Implicit and explicit in the epic is the Jainistic theory ofkarm. An individual is automatically rewarded according to his or her karm and hence there is no need to postulate an intermediary God. Also, one's inherited karm can be overcome by purusharth or 'manly' effort.

Mookmaatee affirms anekaantvaad-which incorporates the universal principles of truth and nonviolence, and sayaadvaad-which propounds the principle of unity of all humankind. The poet stresses the triune of gems -right thinking, right knowledge and right conduct. He attacks the contemporary evils both among the godmen who preach without practising and the laity. This epic is a profound psychological document, analysing compassion, humility, envy, violence, etc. It's a seeker's manual.

The poem blends all the essentials of Jainism in an original symbolic story of homely and elemental characters. The effervescent inventiveness of language and modern poetic techniques made as succulent as possible, endear it to a wide range of readers. Acharya Vidyasagar's literary credo, that a work of art should enable the reader to distinguish between sin and merit, right and wrong, is embodied in his epic. The wordplay is a bait to lure the reluctant reader. Altogether, this work may come to occupyin Jainist literature the place that Tulsidas's Ramcharitmaanas occupies for Hindiphonic Hindus.