________________

*127

this type that is adopted for the gas

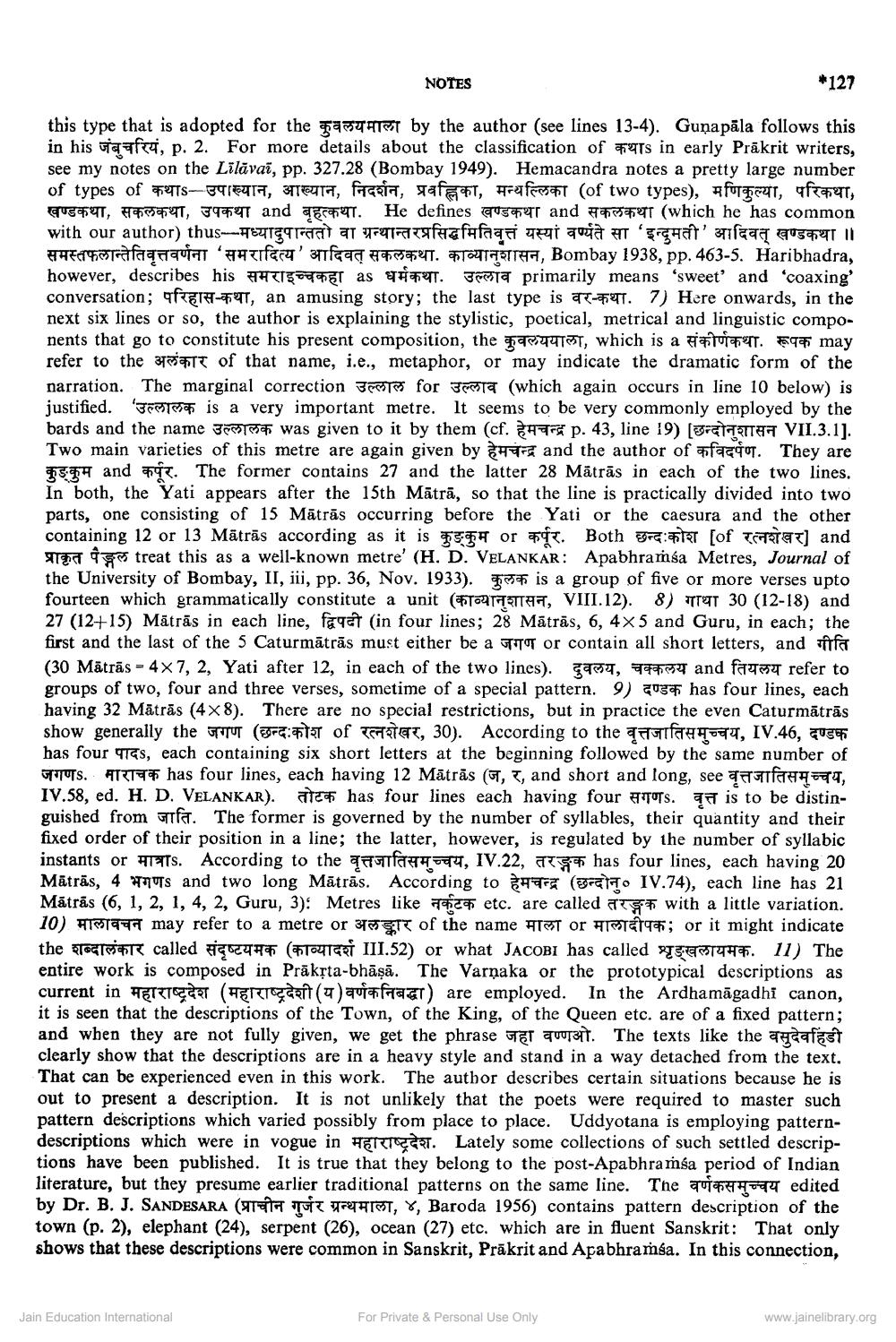

by the author (see lines 13-4). Gunapāla follows this in his if, p. 2. For more details about the classification of Ts in early Prakrit writers, see my notes on the Līlāvai, pp. 327.28 (Bombay 1949). Hemacandra notes a pretty large number of types of कथाs - उपाख्यान, आख्यान, निदर्शन, प्रवह्निका, मन्थल्लिका (of two types), मणिकुल्या, परिकथा, खण्डकथा, सकलकथा, उपकथा and बृहत्कथा. He defines खण्डकथा and सकलकथा (which he has common with our author) thus - मध्यादुपान्ततो वा ग्रन्थान्तरप्रसिद्धमितिवृत्तं यस्यां वर्ण्यते सा 'इन्दुमती' आदिवत् खण्डकथा ॥ समस्तफलान्तेतिवृत्तवर्णना 'समरादित्य' आदिवत् सकलकथा. काव्यानुशासन, Bombay 1938, pp. 463-5. Haribhadra, however, describes his समराइच्चकहा as धर्मकथा. उल्लाव primarily means 'sweet' and 'coaxing ' conversation; -, an amusing story; the last type is . 7) Here onwards, in the next six lines or so, the author is explaining the stylistic, poetical, metrical and linguistic components that go to constitute his present composition, the कुवलययाला, which is a संकीर्णकथा. रूपक may refer to the of that name, i.e., metaphor, or may indicate the dramatic form of the narration. The marginal correction for 3 (which again occurs in line 10 below) is justified. 3 is a very important metre. It seems to be very commonly employed by the bards and the name उल्लालक was given to it by them (cf हेमचन्द्र p. 43, line 19 ) [ छन्दोनुशासन VII. 3.1]. Two main varieties of this metre are again given by and the author of afar. They are gs and . The former contains 27 and the latter 28 Mātrās in each of the two lines. In both, the Yati appears after the 15th Mātrā, so that the line is practically divided into two parts, one consisting of 15 Matras occurring before the Yati or the caesura and the other containing 12 or 13 Mātrās according as it is कुङ्कुम or कर्पूर. Both छन्दः कोश [of रत्नशेखर ] and treat this as a well-known metre' (H. D. VELANKAR: Apabhramsa Metres, Journal of the University of Bombay, II, iii, pp. 36, Nov. 1933). is a group of five or more verses upto fourteen which grammatically constitute a unit (T, VIII.12). 8) 30 (12-18) and 27 (12+15) Mātrās in each line, faqat (in four lines; 28 Mātrās, 6, 4x5 and Guru, in each; the first and the last of the 5 Caturmātrās must either be a T or contain all short letters, and fa (30 Mātrās - 4×7, 2, Yati after 12, in each of the two lines). 3, 4 and faч refer to groups of two, four and three verses, sometime of a special pattern. 9) 03 has four lines, each having 32 Mātrās (4x8). There are no special restrictions, but in practice the even Caturmātrās show generally the जगण (छन्दः कोश of रत्नशेखर, 30 ). According to the वृत्तजातिसमुच्चय, IV.46, दण्डक has fours, each containing six short letters at the beginning followed by the same number of जगणs. माराचक has four lines, each having 12 Mātrās (ज, र, and short and long, see वृत्तजातिसमुच्चय, IV.58, ed. H. D. VELANKAR). has four lines each having four TS. is to be distinguished from fa. The former is governed by the number of syllables, their quantity and their fixed order of their position in a line; the latter, however, is regulated by the number of syllabic instants or मात्राs. According to the वृत्तजातिसमुच्चय, IV. 22, तरङ्गक has four lines, each having 20 Mātrās, 4s and two long Mātrās. According to (o IV.74), each line has 21 Mātrās (6, 1, 2, 1, 4, 2, Guru, 3): Metres like etc. are called with a little variation. 10) मालावचन may refer to a metre or अलङ्कार of the name माला or मालादीपक; or it might indicate the शब्दालंकार called संदृष्टयमक (काव्यादर्श III. 52 ) or what JACOBI has called शृङ्खलायमक. 11) The entire work is composed in Prakṛta-bhāṣā. The Varnaka or the prototypical descriptions as current in महाराष्ट्रदेश (महाराष्ट्रदेशी (य) वर्णक निबद्धा) are employed. In the Ardhamāgadhī canon, it is seen that the descriptions of the Town, of the King, of the Queen etc. are of a fixed pattern; and when they are not fully given, we get the phrase जहा वण्णओ. The texts like the वसुदेवहिंडी clearly show that the descriptions are in a heavy style and stand in a way detached from the text. That can be experienced even in this work. The author describes certain situations because he is out to present a description. It is not unlikely that the poets were required to master such pattern descriptions which varied possibly from place to place. Uddyotana is employing patterndescriptions which were in vogue in. Lately some collections of such settled descriptions have been published. It is true that they belong to the post-Apabhramsa period of Indian literature, but they presume earlier traditional patterns on the same line. The edited by Dr. B. J. SANDESARA (TT, Y, Baroda 1956) contains pattern description of the town (p. 2), elephant (24), serpent (26), ocean (27) etc. which are in fluent Sanskrit: That only shows that these descriptions were common in Sanskrit, Prakrit and Apabhramsa. In this connection,

Jain Education International

NOTES

For Private & Personal Use Only

www.jainelibrary.org