________________

Dying Of Consumption

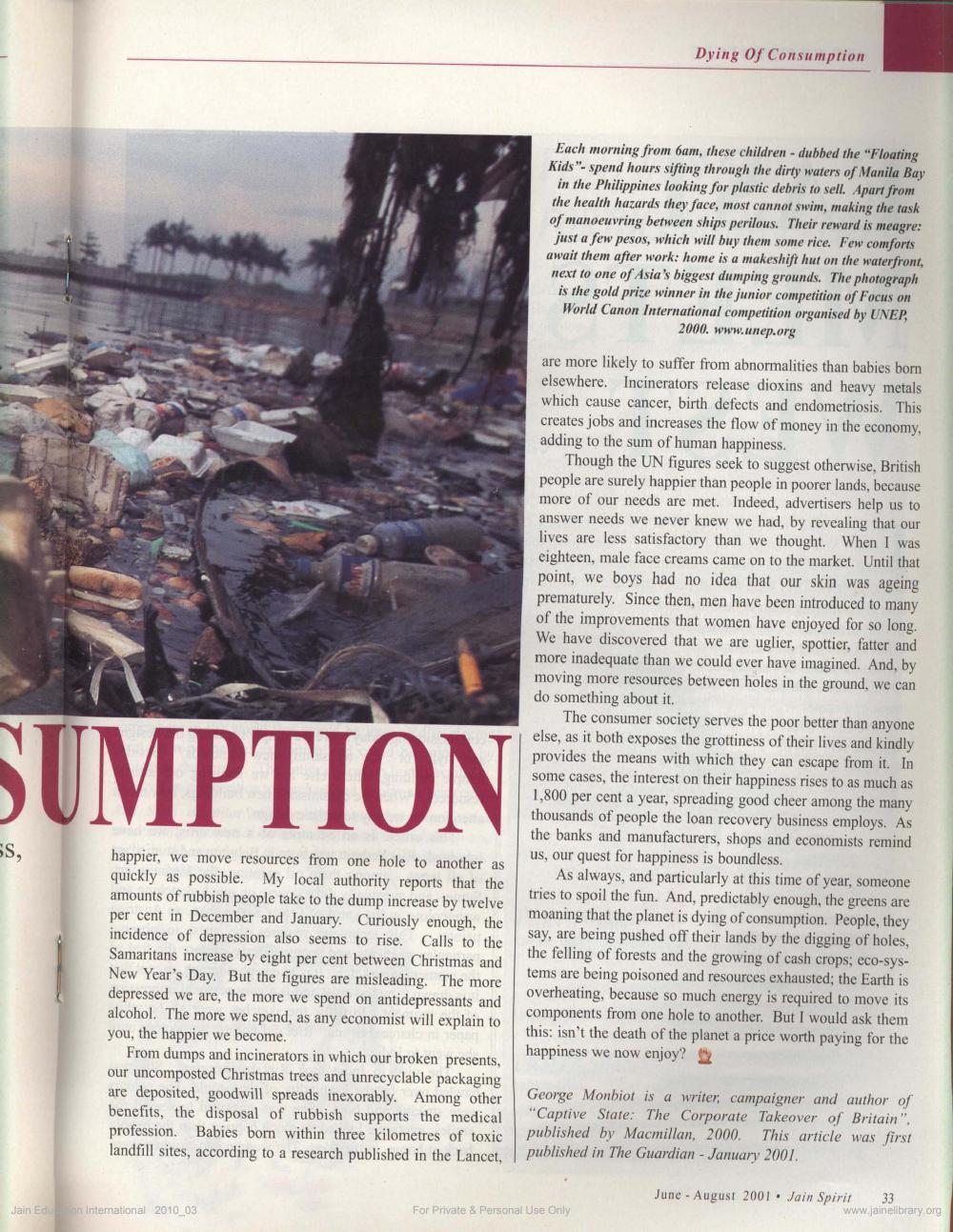

Each morning from bam, these children - dubbed the "Floating Kids"- spend hours sifting through the dirty waters of Manila Bay

in the Philippines looking for plastic debris to sell. Apart from the health hazards they face, most cannot swim, making the task of manoeuvring between ships perilous. Their reward is meagre:

just a few pesos, which will buy them some rice. Few comforts await them after work: home is a makeshift hut on the waterfront, next to one of Asia's biggest dumping grounds. The photograph is the gold prize winner in the junior competition of Focus on World Canon International competition organised by UNEP,

2000. www.unep.org

are more likely to suffer from abnormalities than babies born elsewhere. Incinerators release dioxins and heavy metals which cause cancer, birth defects and endometriosis. This creates jobs and increases the flow of money in the economy, adding to the sum of human happiness.

Though the UN figures seek to suggest otherwise, British people are surely happier than people in poorer lands, because more of our needs are met. Indeed, advertisers help us to answer needs we never knew we had, by revealing that our lives are less satisfactory than we thought. When I was eighteen, male face creams came on to the market. Until that point, we boys had no idea that our skin was ageing prematurely. Since then, men have been introduced to many of the improvements that women have enjoyed for so long. We have discovered that we are uglier, spottier, fatter and more inadequate than we could ever have imagined. And, by moving more resources between holes in the ground, we can do something about it.

The consumer society serves the poor better than anyone else, as it both exposes the grottiness of their lives and kindly provides the means with which they can escape from it. In some cases, the interest on their happiness rises to as much as 1,800 per cent a year, spreading good cheer among the many thousands of people the loan recovery business employs. As the banks and manufacturers, shops and economists remind us, our quest for happiness is boundless.

As always, and particularly at this time of year, someone tries to spoil the fun. And, predictably enough, the greens are moaning that the planet is dying of consumption. People, they say, are being pushed off their lands by the digging of holes, the felling of forests and the growing of cash crops, eco-systems are being poisoned and resources exhausted; the Earth is overheating, because so much energy is required to move its components from one hole to another. But I would ask them this: isn't the death of the planet a price worth paying for the happiness we now enjoy?

SUMPTION

happier, we move resources from one hole to another as quickly as possible. My local authority reports that the amounts of rubbish people take to the dump increase by twelve per cent in December and January. Curiously enough, the incidence of depression also seems to rise. Calls to the Samaritans increase by eight per cent between Christmas and New Year's Day. But the figures are misleading. The more depressed we are, the more we spend on antidepressants and alcohol. The more we spend, as any economist will explain to you, the happier we become.

From dumps and incinerators in which our broken presents, our uncomposted Christmas trees and unrecyclable packaging are deposited, goodwill spreads inexorably. Among other benefits, the disposal of rubbish supports the medical profession. Babies born within three kilometres of toxic landfill sites, according to a research published in the Lancet,

George Monbiot is a writer campaigner and author of "Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain". published by Macmillan, 2000. This article was first published in The Guardian - January 2001.

June - August 2001. Jain Spirit 33

www.jainelibrary.org

Jain Eden

International 2010_03

For Private & Personal Use Only