________________

pariksarsnition

ble the

Nyäyävatāra 2.1 of Siddhasena Divākara; Fate Tarta7917 CAUTEL Tattvārtha - ślokavārttika 1.10.77 of Vidyānanda; also FITTaficarORAF la TA10 – Parikşāmukhasūtra 1.1 of Māņitkyanandin ). Hemacandra also accepts that cognition besides being revelatory of an object is self-revealing, for it is not possible that the cognition of an object could happen to a person who does not intuit the act of knowledge. But self-cognition though invariably present is not a necessary element of the defining characteristic of pramāna, as it is present in all knowledge without exception, including doubt, and the like. Only that characteristic should form part of a definition which is present in the thing defined alone and distinguishes it from all else, or excludes all else. All possible attributes of it are not required to be mentioned. So Hemacandra parting company with his predecessors, however renowned they were, discretely omits any reference to self-cognition in the case of pramāna, and defines it as only Hiztute fuit.

The term 'Samyak' is an epithet of ‘nirnaga' (definitive cognition), because it alone can be right or otherwise. The object (artha) by itself is neither right nor otherwise, and so does not require any such qualifier. An epithat is meaningful only when there is possibility (sambhava) or deviation (vyabhicăra). No one qualifies 'fire' as 'hot' or 'cold' because there is not the possibility of its being cold, and fire does not deviate from heat.(i.e. is always found with it). As Kumārila Bhatta says:

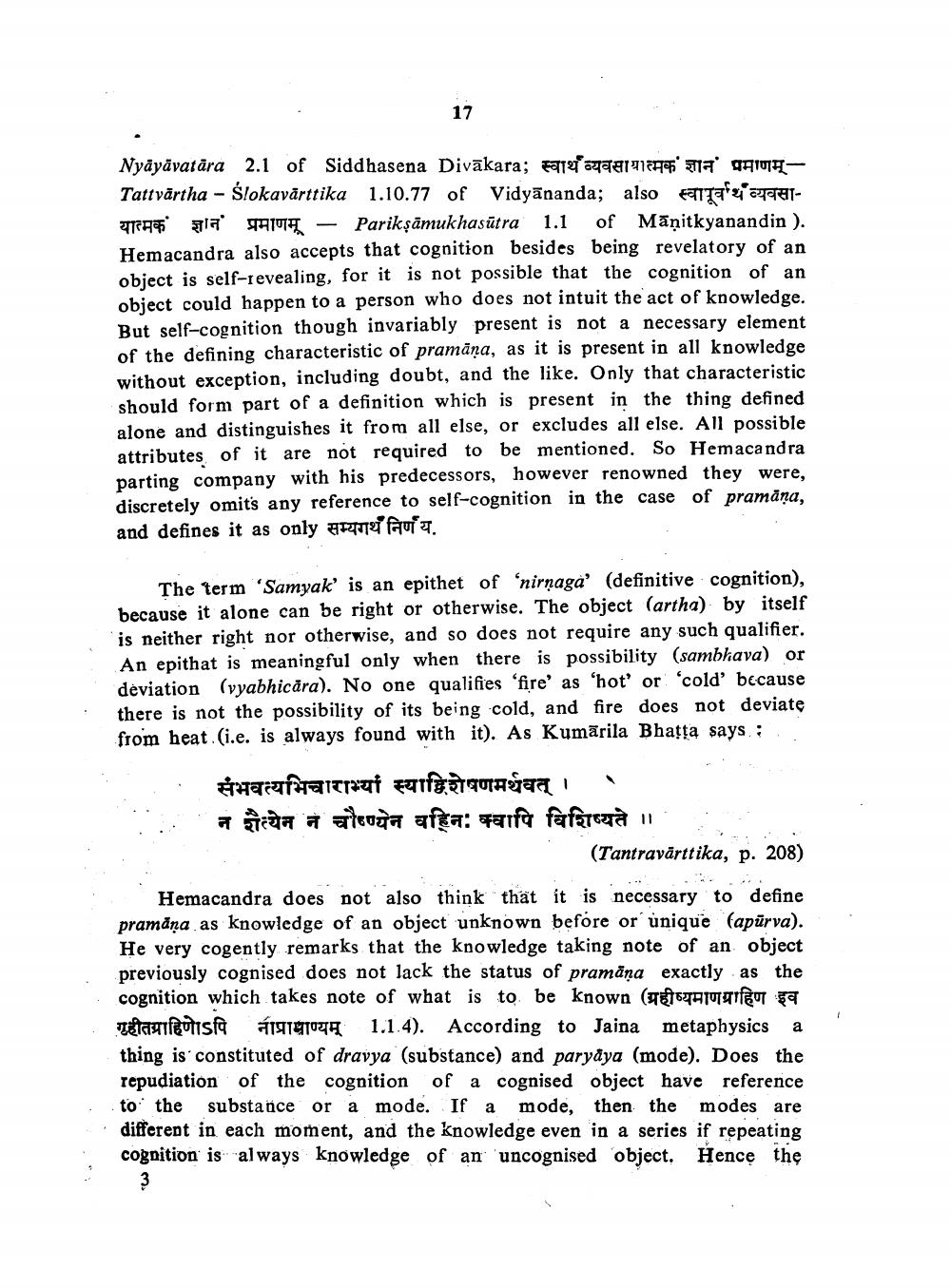

:: TARTITITI FOTEL Tuaja i i .. न शैत्येन न चौहण्येन वहिन: क्वापि विशिष्यते ॥

(Tantravārttika, p. 208) Hemacandra does not also think that it is necessary to define pramana as knowledge of an object unknown before or unique (apūrva). He very cogently remarks that the knowledge taking note of an object previously cognised does not lack the status of pramāna exactly as the cognition which takes note of what is to be known (ग्रहीष्यमाणग्राहिण इव retagiotisfa 519191074 1.1.4). According to Jaina metaphysics a thing is constituted of dravya (substance) and paryaya (mode). Does the repudiation of the cognition of a cognised object have reference to the substance or a mode. If a mode, then the modes are different in each moment, and the knowledge even in a series if repeating cognition is always knowledge of an uncognised object. Hence the

3