________________

RELIGION AND WOMEN

-124

rated with monks in the writing of a book, or who have inspired them (Shanta 1985, 140-42). However, as testimony that intellectual life could be brilliant among nuns, we can refer to the so-called Kuratti Adigal, a teaching institution managed by female ascetics in Tamil Nadu (ninth to eleventh century: Shäntä 1985, 171ff.).

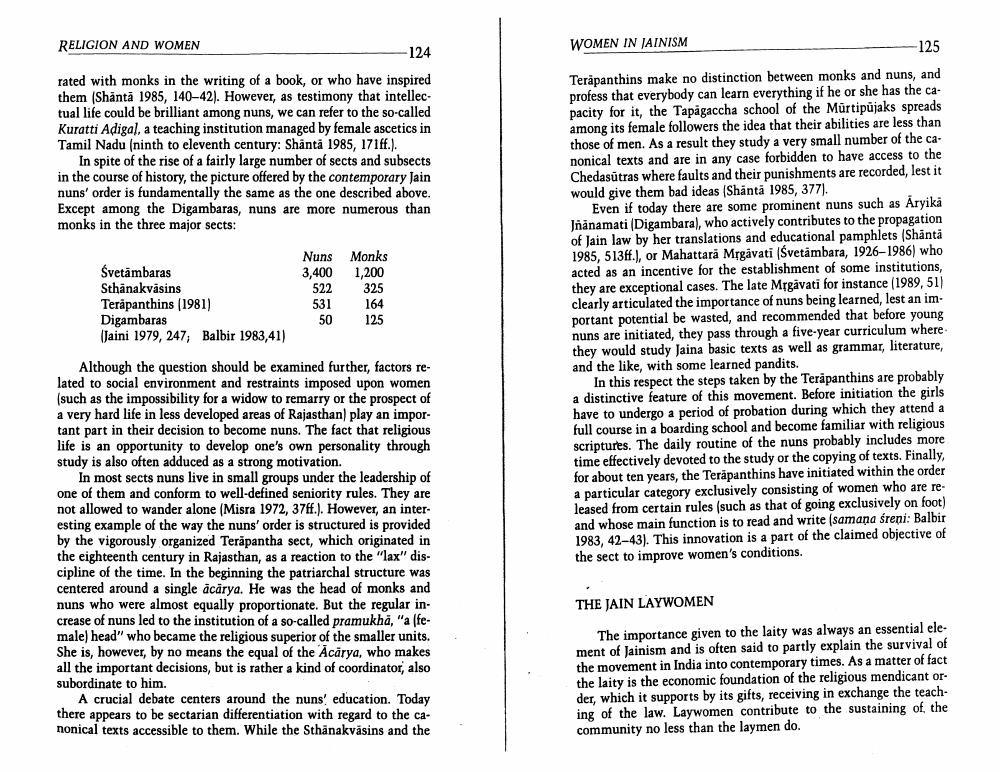

In spite of the rise of a fairly large number of sects and subsects in the course of history, the picture offered by the contemporary Jain nuns' order is fundamentally the same as the one described above. Except among the Digambaras, nuns are more numerous than monks in the three major sects:

Śvetambaras

Sthanakväsins

Terapanthins (1981)

Digambaras

(Jaini 1979, 247, Balbir 1983,41)

Nuns 3,400

522

531

50

Monks

1,200

325

164

125

Although the question should be examined further, factors related to social environment and restraints imposed upon women (such as the impossibility for a widow to remarry or the prospect of a very hard life in less developed areas of Rajasthan) play an important part in their decision to become nuns. The fact that religious life is an opportunity to develop one's own personality through study is also often adduced as a strong motivation.

In most sects nuns live in small groups under the leadership of one of them and conform to well-defined seniority rules. They are not allowed to wander alone (Misra 1972, 37ff.). However, an interesting example of the way the nuns' order is structured is provided by the vigorously organized Terapantha sect, which originated in the eighteenth century in Rajasthan, as a reaction to the "lax" discipline of the time. In the beginning the patriarchal structure was centered around a single acarya. He was the head of monks and nuns who were almost equally proportionate. But the regular increase of nuns led to the institution of a so-called pramukha, "a (female) head" who became the religious superior of the smaller units. She is, however, by no means the equal of the Acarya, who makes all the important decisions, but is rather a kind of coordinator, also subordinate to him.

A crucial debate centers around the nuns' education. Today there appears to be sectarian differentiation with regard to the canonical texts accessible to them. While the Sthanakväsins and the

WOMEN IN JAINISM

-125

Terapanthins make no distinction between monks and nuns, and profess that everybody can learn everything if he or she has the capacity for it, the Tapagaccha school of the Mürtipujaks spreads among its female followers the idea that their abilities are less than those of men. As a result they study a very small number of the canonical texts and are in any case forbidden to have access to the Chedasutras where faults and their punishments are recorded, lest it would give them bad ideas (Shäntä 1985, 377).

Even if today there are some prominent nuns such as Āryika Jñänamati (Digambara), who actively contributes to the propagation of Jain law by her translations and educational pamphlets (Shäntä 1985, 513ff.), or Mahattara Mrgavati (Śvetämbara, 1926-1986) who acted as an incentive for the establishment of some institutions, they are exceptional cases. The late Mrgavati for instance (1989, 51) clearly articulated the importance of nuns being learned, lest an important potential be wasted, and recommended that before young nuns are initiated, they pass through a five-year curriculum where they would study Jaina basic texts as well as grammar, literature, and the like, with some learned pandits.

In this respect the steps taken by the Terapanthins are probably a distinctive feature of this movement. Before initiation the girls have to undergo a period of probation during which they attend a full course in a boarding school and become familiar with religious scriptures. The daily routine of the nuns probably includes more time effectively devoted to the study or the copying of texts. Finally, for about ten years, the Terapanthins have initiated within the order a particular category exclusively consisting of women who are released from certain rules (such as that of going exclusively on foot) and whose main function is to read and write (samana śreni: Balbir 1983, 42-43). This innovation is a part of the claimed objective of the sect to improve women's conditions.

THE JAIN LAYWOMEN

The importance given to the laity was always an essential element of Jainism and is often said to partly explain the survival of the movement in India into contemporary times. As a matter of fact the laity is the economic foundation of the religious mendicant order, which it supports by its gifts, receiving in exchange the teaching of the law. Laywomen contribute to the sustaining of the community no less than the laymen do.