________________

54

EPIGRAPHIA INDICA.

[VOL. XXIV.

village was purchased by a merchant named Chandra from the Brahmins. Beyond this our inscription furnishes no such information as has not already been supplied by the Dudia plates written in the same year as this record as well as by the Chammak and Siwani plates which were issued in the eighteenth year of the reign of this Mahārāja Pravarasēna II. But the similarity of the Tirodi plates with the present record is striking. Both these grants were issued in the same year and their language is also very much similar. As a matter of fact some of the terms and words in this inscription can be properly understood only when compared with the Tirōḍi plates. Mistakes due to the engraver are very numerous in this inscription and many of them have been corrected with the help of the Tirōdi plates.

Like his other inscriptions the present one also supplies us with the stereotyped genealogy of Pravarasēna II. But the first plate being lost the genealogy from Gautamiputra only survives. After the genealogy the details of the grant are given. The inscription ends with the date and the name of the writer.

In one point our inscription offers information which makes it of great interest to students of administrative history. Unlike the other plates of the Vākāṭaka kings this record was written by one Kōṭṭadeva who styles himself as Rajuka. This is the first time we meet with the term Rajuka in so late a period. Rajuka is primarily a term to indicate an officer whose undoubted existence in the 3rd century B.C. is proved by the inscriptions of Asoka.. Up till the middle of the second century A.D. South India1 at least kept up the use of this official. The reference to Mahāmātras, Rajjukas and Sancharins indicates that the old tradition was kept up in Southern India. When the Vakatakas came to the forefront, on the decline of the Kushaņas, they probably made an endeavour to revive the old institutions. The Guptas, who were mainly a North-Indian power, were greatly influenced by the Kushanas and adopted many foreign features in their administrative machinery. The Vākāṭakas were more in the south and so could retain the earlier official terms. For this reason we find that in most of the records of this Vākāṭaka king occur certain revenue terms which have not been found in any other copper-plate and of which no satisfactory explanation can yet be offered. It is clear from the record that the Rajuka was still an officer mainly concerned with land and revenue. It is strange that in no other records of this period do we meet with this term. The reason seems to be that though all land transactions were negotiated under his jurisdiction, only in very important cases the Rajuka himself used to participate, the rest being done by subordinate officers. The date of the record being given in regnal years cannot be verified. None of the places mentioned in this inscription can be identified.

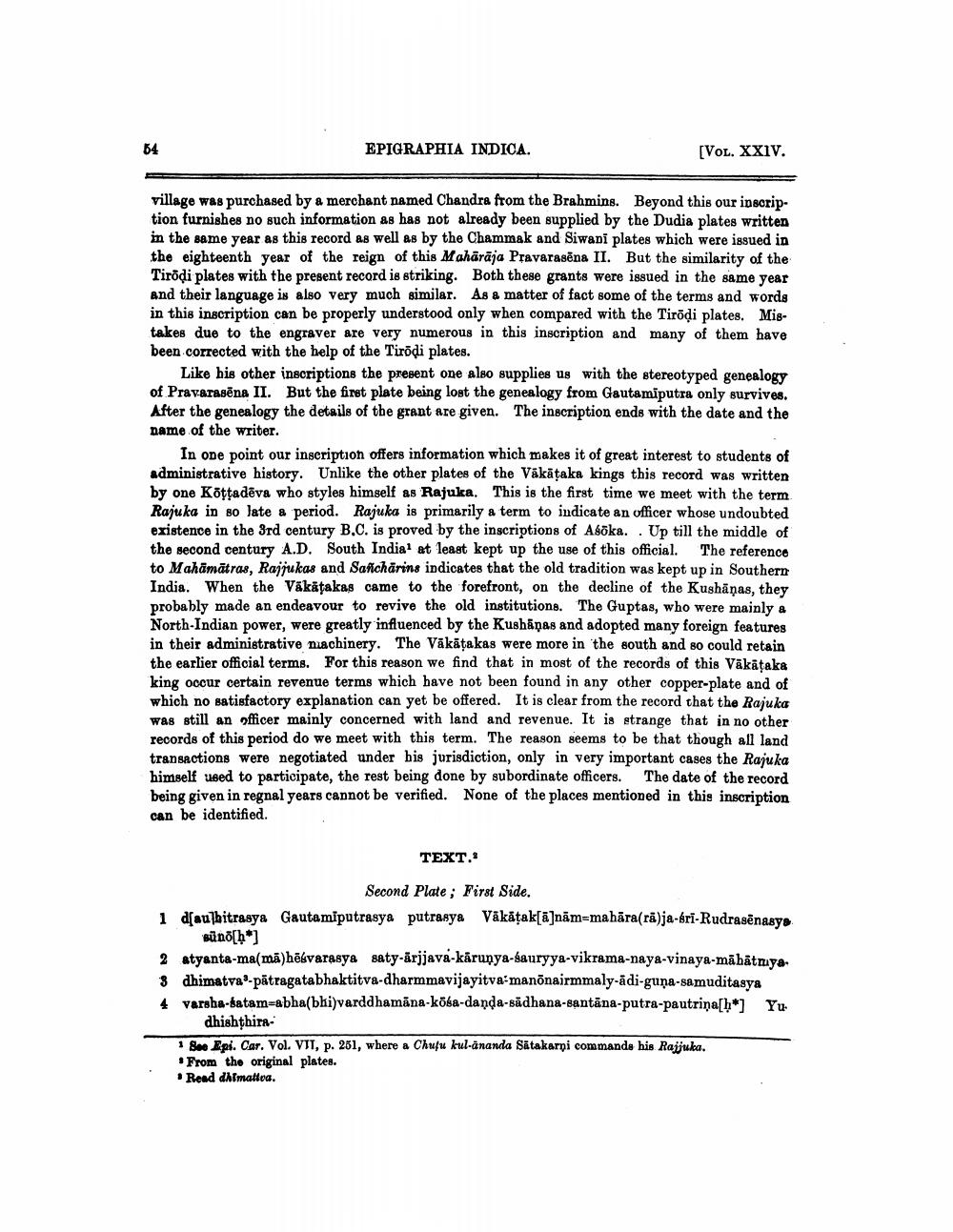

TEXT."

Second Plate; First Side.

1 aulbitraaya Gautamiputrasya putrasya Väkiṭak[A]nām-mahāra(cā)ja-4rī-Rudrasinasyo ==[h*]

2 atyanta-ma(mā) hēśvarasya saty-ärjjava-kāruṇya-sauryya-vikrama-naya-vinaya-māhātmya. 3 dhimatva patragatabhaktitva-dharmmavijayitva manönairmmaly-adi-gupa-samuditasya

4 varsha-satam-abha(bhi)varddhamāna-kōsa-daṇḍa-sādhana-santana-putra-pautriņa[b*] Yu

dhishthira

1 See Epi. Car. Vol. VII, p. 251, where a Chufu kul-ananda Satakarni commands his Rajjuka.

From the original plates.

• Read dhimativa.