________________

184

EPIGRAPHIA INDICA.

[Vol. IV.

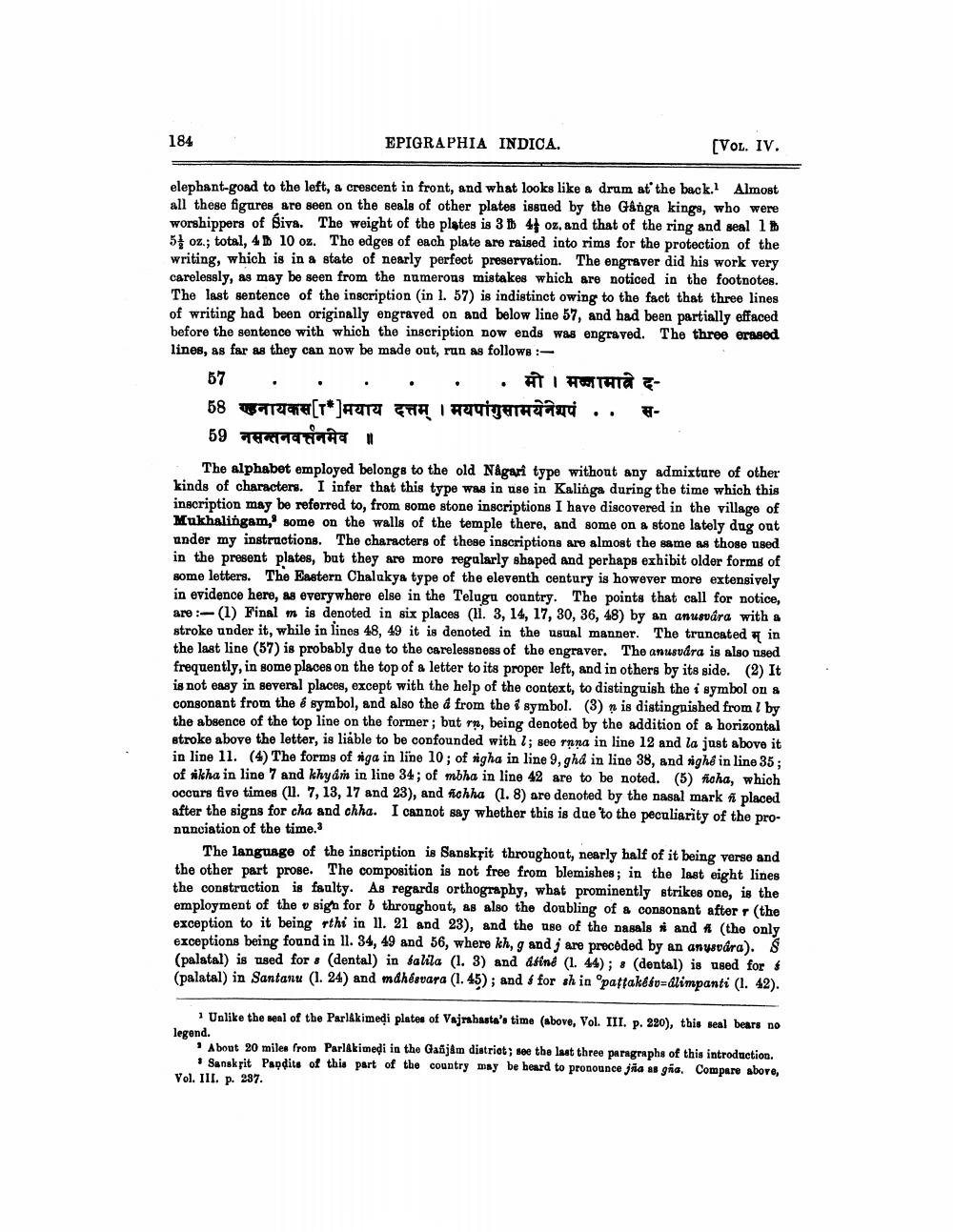

elephant-goad to the left, a crescent in front, and what looks like a drum at the back. Almost all these figures are seen on the seals of other plates issued by the Ganga kings, who were worshippers of Siva. The weight of the pletes is 3 b4 oz, and that of the ring and seal 18 5 oz.; total, 4 D 10 oz. The edges of each plate are raised into rims for the protection of the writing, which is in a state of nearly perfect preservation. The engraver did his work very carelessly, as may be seen from the numerous mistakes which are noticed in the footnotes. The last sentence of the inscription (in l. 57) is indistinct owing to the fact that three lines of writing had been originally engraved on and below line 57, and had been partially effaced before the sentence with which the inscription now ends was engraved. The three erased lines, as far as they can now be made out, run as follows:

57 . . . . . . TIHTHT - 58 warne[T*]per HA I HAVITHTHard .. - 59 72119NTAS

The alphabet employed belongs to the old Någari type without any admixture of other kinds of characters. I infer that this type was in use in Kalinga during the time which this inscription may be referred to, from some stone inscriptions I have discovered in the village of Mukhalingam, some on the walls of the temple there, and some on a stone lately dag ont under my instructions. The characters of these inscriptions are almost the same as those used in the present plates, but they are more regularly shaped and perhaps exhibit older forms of some letters. The Eastern Chalukya type of the eleventh century is however more extensively in evidence here, as everywhere else in the Telugu country. The points that call for notice, are :-(1) Final m is denoted in six places (11. 3, 14, 17, 30, 36, 48) by an anusvára with a stroke under it, while in lines 48, 49 it is denoted in the usual manner. The truncated in the last line (57) is probably due to the carelessness of the engraver. The anusvára is also used frequently, in some places on the top of a letter to its proper left, and in others by its side. (2) It is not easy in several places, except with the help of the context, to distinguish the i symbol on & consonant from the & symbol, and also the from the i symbol. (3) n is distinguished from l by the absence of the top line on the former ; but rn, being denoted by the addition of a horizontal stroke above the letter, is liable to be confounded with 7; see rnna in line 12 and la just above it in line 11. (4) The forms of #ga in line 10; of nigha in line 9, ghd in line 38, and nighé in line 35; of sikha in line 7 and khyd in line 34; of mbha in line 42 are to be noted. (5) ficha, which occurs five times (11. 7, 13, 17 and 23), and fichha (1.8) are denoted by the nasal mark fi placed after the signs for cha and chha. I cannot say whether this is due to the peculiarity of the pronunciation of the time.

The language of the inscription is Sanskřit throughout, nearly half of it being verse and the other part prose. The composition is not free from blemishes; in the last eight lines the construction is faulty. As regards orthography, what prominently strikes one, is the employment of the v sigh for b throughout, as also the doubling of & consonant after the exception to it being rthi in 11. 21 and 23), and the use of the nasals # and # (the only exceptions being found in ll. 34, 49 and 56, where kh, g and j are preceded by an anusvára). $ (palstal) is used for 8 (dental) in salila (1. 3) and afiné (1. 44); . (dental) is used for $ (palatal) in Santanu (1. 24) and mdhésvara (1.45); and 6 for sh in 'pattakésv=dlimpanti (1. 42).

1 Unlike the son of the ParlAkimedi plates of Vajrahasta's time (above, Vol. III. p. 320), this seal bears no legend.

About 20 miles from PariAkimedi in the Gañjam distriet; see the last three paragraphs of this introduction.

Sanskrit Papdits of this part of the country may be beard to pronounce ja as gia. Compare above, Vol. III. p. 237.