________________

$$ 361-365]

ON THE MODERN INDO-ARYAN VERNACULARS

with it we may compare the sound of the Northern Panjabi and Lahnda uncompounded j, which tends to become y when medial (NP. Gr. xiii). Compare also the remarks of Bs. (Cp. Gr. i, 71) on the pronunciation of L. majh, a buffalo cow, which he says is something like meyh, and Hl.'s suggestion (Gd. Gr. 18, n. 1) that the sound of jh in that word may be compared with that given to g in the word 'lebendig' in the Rhenish Provinces.

364. As regards non-cuphonic uncompounded in Pr., it may be concluded from analogy that it was more firmly pronounced than the euphonic", though still nothing like so strong as an English v. J. Bloch (FLM. 156) points out how in Marathi a European v has to be represented by vh (cf. Kōn. sirvhidor for Portuguese servidor, a servant, LSI. VII, 169). So, in other languages, such as Bengali or Hindi, an English v is sometimes represented by v and sometimes by bh, neither of which exactly gives the right sound. Moreover, this Pr. original uncompounded non-euphonic v must have possessed an obscure sound fluctuating between b and v, exactly as is the case in Bihari at the present day, in which language it is often impossible to say which sound is intended. A good example is the B. paābathi or pavathi, hз obtains. Pandits generally write it with a b, but others (when writing Nagari) often use v and I myself, who spoke the language for years, cannot say which it is. In the Kaithi alphabet commonly used in Bihar, and in the Bg. alphabet, the same character does duty for both b and v. As for Pr. the grammars show the confusion between these two sounds. An intervocalic uncompounded p or b became v according to He. i, 231, 237, and yet in Ap. (He. iv, 396) an original intervocalic p generally became b. It is significant that Mk. in xvii, 2, -written in Orissa, a country where at the present day no distinction is made between b and v,-the change of p>b in Ap. is not mentioned, it being left to be inferred that according to Mk. the letter p always> the letter v, however that letter may have been pronounced in the Pr. of Eastern India. RT. distinctly says that v does not occur in Pr., and equally clearly says that intervocalic p becomes b (not v) in Mahārāṣṭri; but how exactly he sounded the b is not stated. He was a native of Western Bengal (see JRAS., 1925, 231 ff.) In all Prakrits an initial v remained unchanged in writing.

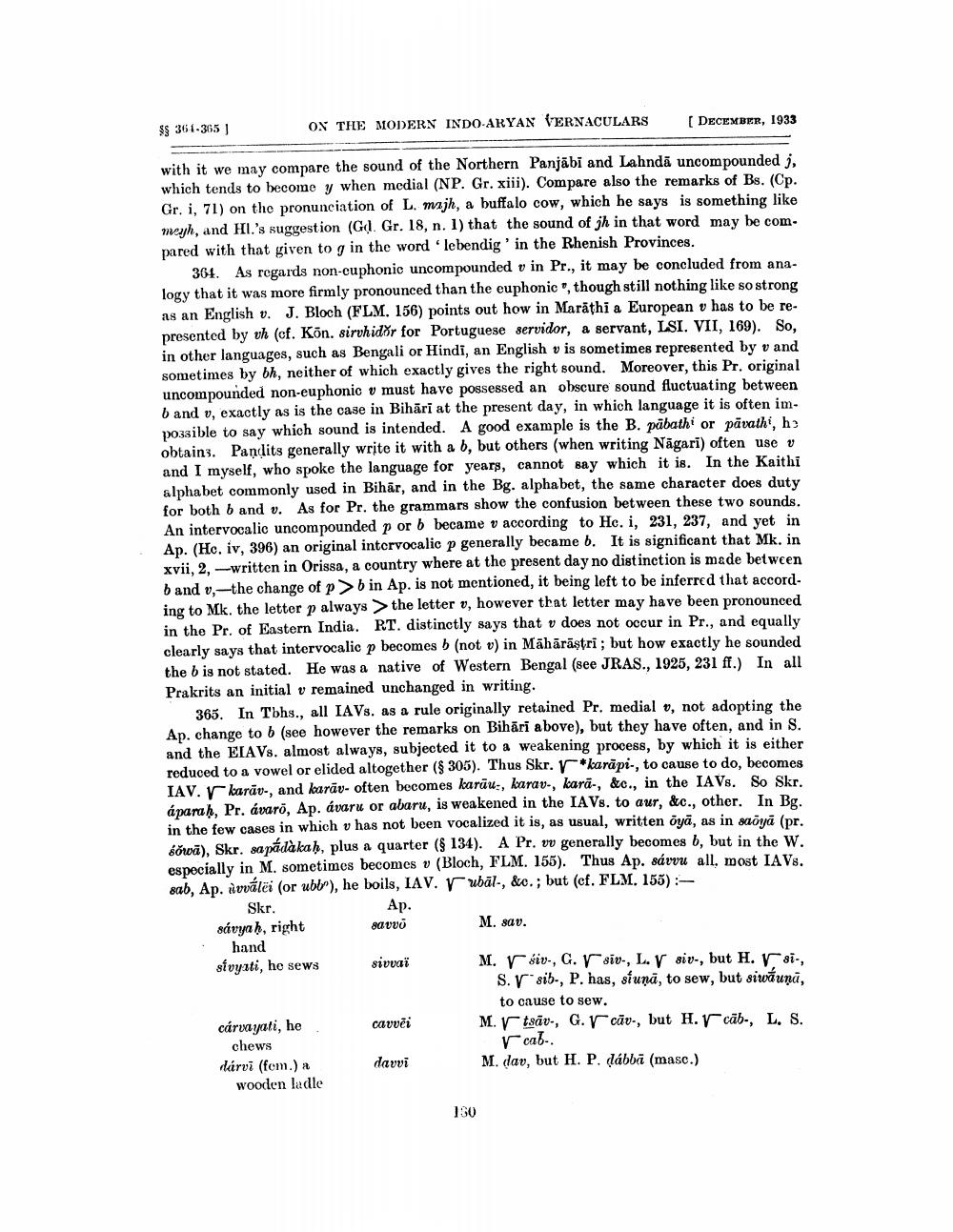

365. In Tbhs., all IAVs. as a rule originally retained Pr. medial v, not adopting the Ap. change to b (see however the remarks on Bihārī above), but they have often, and in S. and the EIAVs. almost always, subjected it to a weakening process, by which it is either reduced to a vowel or elided altogether (§ 305). Thus Skr. *karapi-, to cause to do, becomes IAV. V karav-, and karäv- often becomes karāu:, karav-, kara-, &c., in the IAVs. So Skr. áparaḥ, Pr. ávaro, Ap. ávaru or abaru, is weakened in the IAVs. to aur, &c., other. In Bg. in the few cases in which v has not been vocalized it is, as usual, written öyā, as in saōyā (pr. sowa), Skr. sapádakaḥ, plus a quarter (§ 134). A Pr. vv generally becomes b, but in the W. especially in M. sometimes becomes v (Bloch, FLM. 155). Thus Ap. sávvu all, most IAVs. sab, Ap. avvalei (or ubb"), he boils, IAV. Vubal-, &c.; but (cf. FLM. 155):

Skr. sávyaḥ, right

hand sivyati, he sews

cárvayati, he

chews

dárvi (fem.) a wooden ladle

Ap. savvō

sivvaï

cavvei

[ DECEMBER, 1933

davvi

130

M. sav.

M.

iv, G. Vsiv-, L. V siv-, but H. Vsi-, S. V sib-, P. has, siuna, to sew, but siwaunā,

to cause to sew.

M. Vtsav-, G. cav-, but H. Vcab-, L. S. Vcab

M. dav, but H. P. dábbā (masc.)