________________

§§ 347-348]

ON THE MODERN INDO-ARYAN VERNACULARS

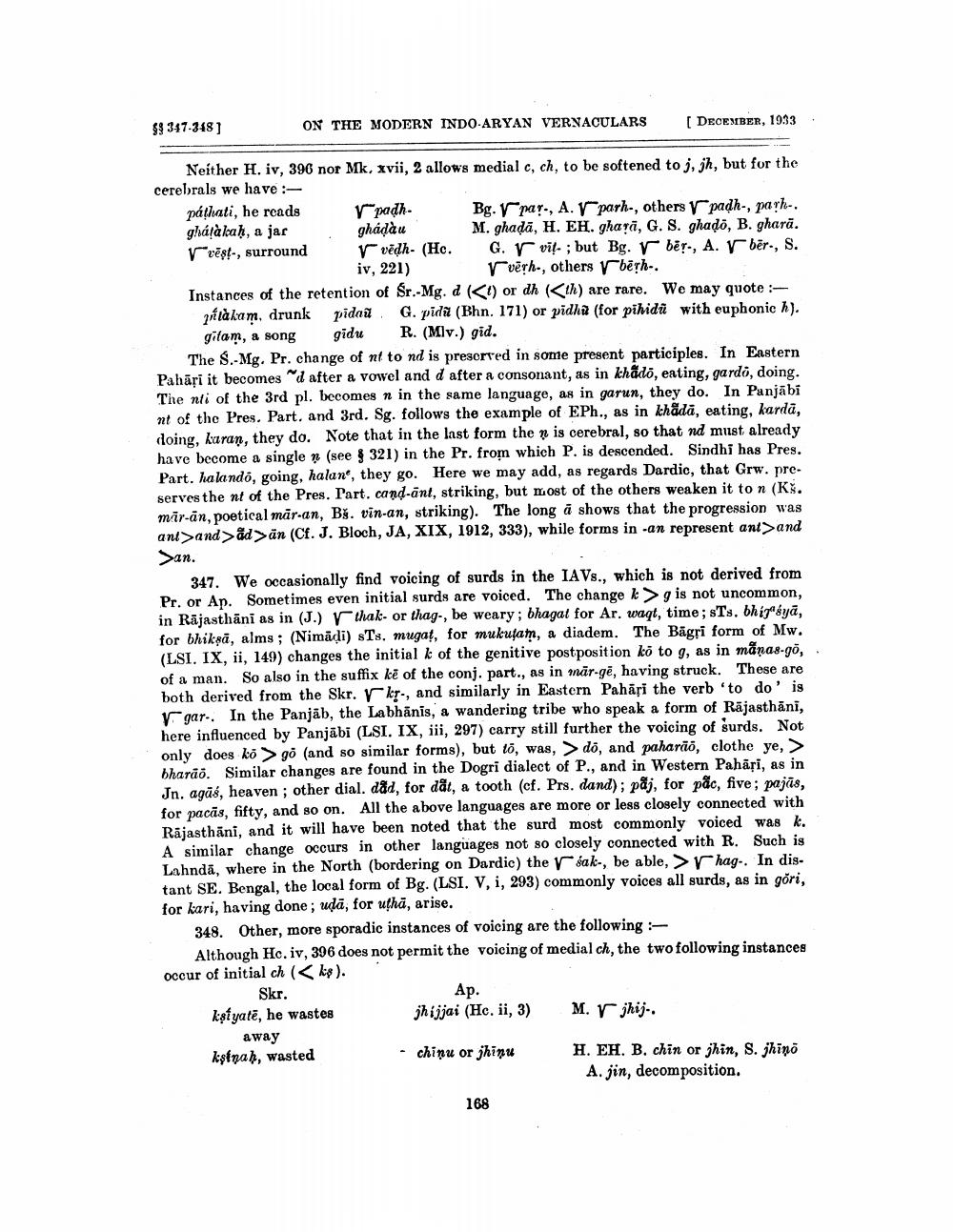

Neither H. iv, 396 nor Mk. xvii, 2 allows medial c, ch, to be softened to j, jh, but for the cerebrals we have:

páthati, he reads gháṭakaḥ, a jar V vest-, surround

Ypadh. ghada

V vēdh- (Hc. iv, 221)

[DECEMBER, 1933

Bg. par-, A. V parh-, others Vpadh-, park-. M. ghada, H. EH. ghara, G. S. ghado, B. ghara. G. vit; but Bg. V ber-, A. V bēr-, S. verh-, others bērh..

Instances of the retention of Sr.-Mg. d (<t) or dh (<th) are rare. We may quote:plakam, drunk pidau G. pidu (Bhn. 171) or pidhu (for pihidu with euphonic h). gitam, a song gidu R. (Mlv.) gid.

The S.-Mg. Pr. change of nf to nd is preserved in some present participles. In Eastern Pahari it becomes "d after a vowel and d after a consonant, as in khado, eating, gardo, doing. The nti of the 3rd pl. becomes n in the same language, as in garun, they do. In Panjabi nt of the Pres. Part. and 3rd. Sg. follows the example of EPh., as in khäda, eating, kardā, doing, karan, they do. Note that in the last form the n is cerebral, so that nd must already have become a single (see § 321) in the Pr. from which P. is descended. Sindhi has Pres. Part. halandó, going, halan, they go. Here we may add, as regards Dardic, that Grw. preserves the nt of the Pres. Part. cand-ant, striking, but most of the others weaken it to n (Ks. mar-an, poetical mar-an, Bs. vin-an, striking). The long a shows that the progression was ant>and>ad>än (Cf. J. Bloch, JA, XIX, 1912, 333), while forms in -an represent ant>and

>an.

347. We occasionally find voicing of surds in the IAVs., which is not derived from Pr. or Ap. Sometimes even initial surds are voiced. The change >g is not uncommon, in Rajasthani as in (J.) thak- or thag-, be weary; bhagat for Ar. waqt, time; sTs. bhigya, for bhikṣā, alms; (Nimaḍi) sTs. mugat, for mukutam, a diadem. The Bagri form of Mw. (LSI. IX, ii, 149) changes the initial k of the genitive postposition ko to g, as in manas-gō, of a man. So also in the suffix ke of the conj. part., as in mär-ge, having struck. These are both derived from the Skr. kr-, and similarly in Eastern Pahari the verb 'to do' is Vgar. In the Panjab, the Labhānīs, a wandering tribe who speak a form of Rajasthani, here influenced by Panjabi (LSI. IX, iii, 297) carry still further the voicing of surds. Not only does ko> go (and so similar forms), but to, was, > do, and paharão, clothe ye, > bharão. Similar changes are found in the Dogri dialect of P., and in Western Pahari, as in Jn. agās, heaven; other dial. dåd, for dåt, a tooth (cf. Prs. dand); paj, for pac, five; pajās, for pacās, fifty, and so on. All the above languages are more or less closely connected with Rajasthani, and it will have been noted that the surd most commonly voiced was k. A similar change occurs in other languages not so closely connected with R. Such is Lahnda, where in the North (bordering on Dardic) the sak-, be able, >hag-. In distant SE. Bengal, the local form of Bg. (LSI. V, i, 293) commonly voices all surds, as in gori, for kari, having done; uda, for utha, arise.

348. Other, more sporadic instances of voicing are the following:

Although Hc. iv, 396 does not permit the voicing of medial ch, the two following instances occur of initial ch (<ks).

Skr.

katyate, he wastes

away ksinah, wasted

Ap. jijjai (He. ii, 3)

chiņu or jhiņu

168

M. jij..

H. EH. B. chin or jhin, S. jhiņo A. jin, decomposition.