________________

154

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY

[ August, 1929

itself, a poet, in a similar situation, has said (7, 57, 2) a vitaye sadata pipriyanah. Similarly, the idea of Tischgenossenschaft is expressed in Sanskrit not by admasadya or its equivalents but by the word sahabhojana or its equivalents.

It thus becomes evident that neither the explanation of Yaska nor those of the abovementioned exegetists, based on it, are correct and that the meaning of the word admasad is still a riddle. As it happens, the four passages in which the word occurs, as well as other connected passages of the RV., furnish enough clues to enable one to solve this riddle.

It is shown by 1, 124. 40: admasan na sasato bodhayanti that the awakening of others is a characteristic of the admasadah ; and it is similarly made clear by 6, 30, 30 : ni parvata admasa do m seduh that sitting down is another characteristic of the admasadah. A comparison therefore of the upamanas in the RV passages in which sitting is the sámánya-dharma with the words that are used as subjects of verbs meaning to awaken 'in other RV passages 47 will show us what persons or things are described by the RV poets as both awakening others and sitting down and will thus enable us to determine the meaning of admasad.

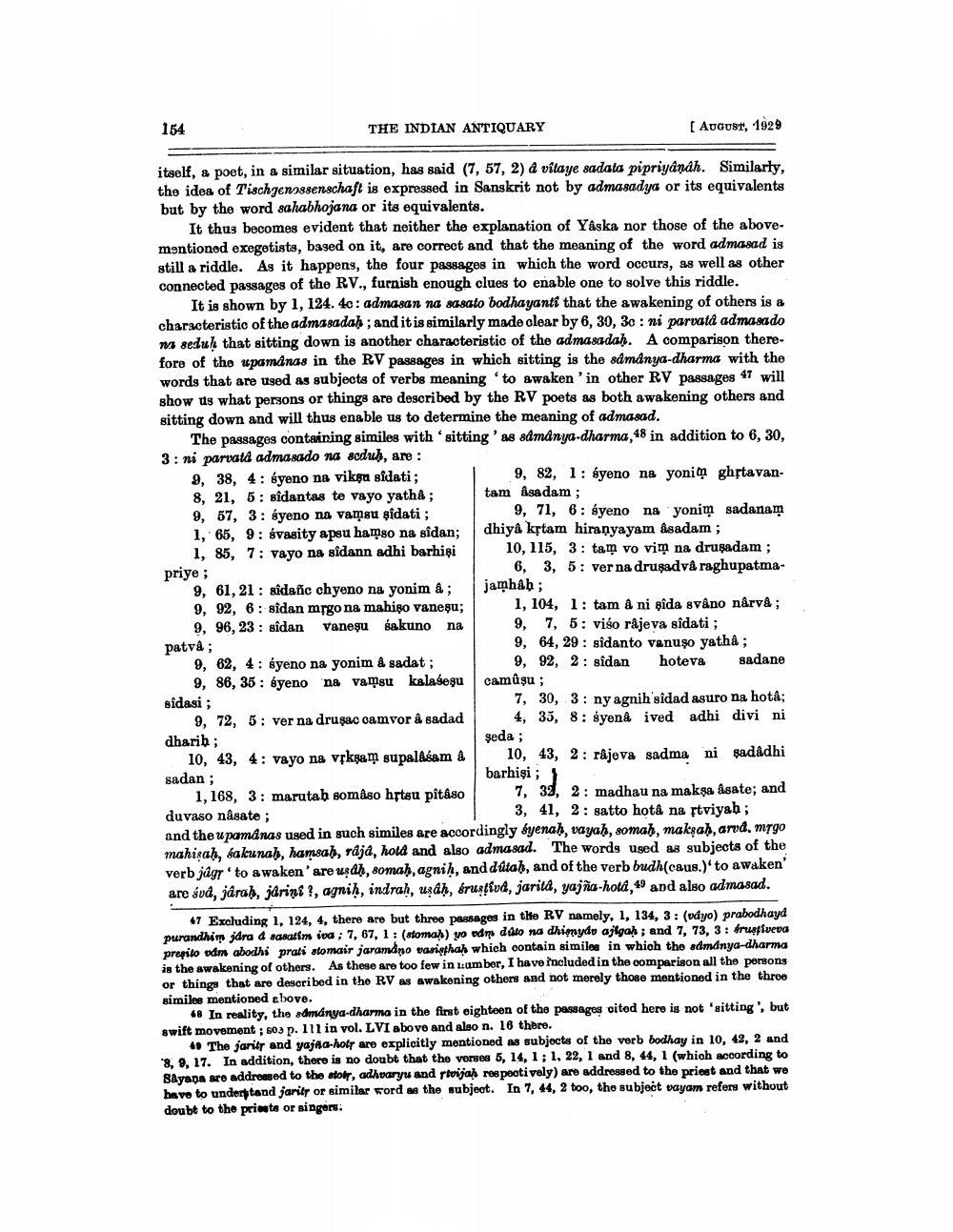

The passages containing similes with 'sitting as admánya-dharma, 48 in addition to 6, 30, 3: ni parvata admasado na seduh, are : 9, 38, 4: byeno na vikga sidati;

9, 82, 1: syeno na yoni ghftavan8, 21, 5: sidantas te vayo yatha ;

tam Asa dam; 9, 57, 3: syeno na vamsu sidati;

9, 71, 6: syeno na yonim sadanam 1, 65, 9: śvasity apsu hamso na sidan;

dhiya krtam hiranyayam Asadam; 1, 85, 7: vayo na sidann adhi barhişi I 10, 115, 3: tam vo vim na druşadam; priye ;

6, 3, 5: ver na druşadvå raghupatma9, 61, 21: sidanc chyeno na yonim &; jamhab; 9, 92, 6: sidan mrgo na mahişo vaneşu; 1, 104, 1: tam ani şîda sváno nárva; 9, 96, 23 : sidan vaneşu sakuno na 9, 7, 5: viso rájeva sidati;

9, 64, 29: sidanto vanuşo yatha ; 9, 62, 4: śyeno na yonim & sadat;

9, 92, 2: sidan hoteva sadane 9, 86, 35 : byeno na vaņgu kalasegu camûsu; sidasi ;

7, 30, 3: ny agnih 'sidad asuro na hota; 9, 72, 5: ver na druşac oamvor & sadad 4, 35, 8: syen& ived adhi divi ni dharib;

$eda ; 10, 43, 4: vayo na vřkşam supalAsam a 10, 43, 2: râjeva sadma ni sadadhi sadan;

barhişi ; } 1,168, 3: marutab somaso hfteu pitaso

7, 38, 2: madhau na makşa asate; and duvaso nasate ;

3, 41, 2: satto hotâ na ftviyab; and the upamanas used in such similes are accordingly byenah, vayah, somah, makşah, arvd. mrgo mahişah, sakunah, hamsah, raja, hold and also admasad. The words used as subjects of the verb jágr to awaken' are uşdh, somah, agnih, and ddtah, and of the verb budh(caus.)' to awaken' are svd, jdrah, jdrini ?, agnih, indrah, usah, śrustivd, jarita, yajña-hotd, 49 and also admasad.

patva:

47 Excluding 1, 124, 4, there are but three passages in the RV namely, 1, 134, 3: (vdyo) prabodhayd purandhim jdra d aasatim iva; 7, 67, 1: (atoma)) yo odn ddto na dhimydo ajlgah ; and 7, 73, 3: fruiveva prepito odm abodhi prati stomair jaramdno vasinphah which contain similes in which the admdnya-dharma is the awakening of others. As these are too few in :umber, I have included in the comparison all the persons or things that are described in the RV as awakening others and not merely those mentioned in the three similee mentioned above.

48 In reality, the admdnya-dharma in the first eighteen of the passages oited here is not 'sitting, but swift movement: 603 p. 111 in vol. LVI above and also n. 16 there.

4. The jarity and yajaa-hots are explicitly mentioned as subjects of the verb bodhay in 10, 42, 2 and 8, 9, 17. In addition, there is no doubt that the verses 5, 14, 1; 1, 22, 1 and 8, 44, 1 (which according to Sayapa aro addressed to the tour, adhuaryu and revijah respectively) are addressed to the priest and that we have to understand jarits or similar word as the subject. In 7, 44, 2 too, the subject vayam refers without doubt to the prints or singers: