________________

EBRUARY, 1926 ] NEMARKS ON THE ANDAMAN ISLANDERS AND THEIR COUNTRY

21

REMARKS ON THE ANDAMAN ISLANDERS AND THEIR COUNTRY.

By Str RICHARD C. TEMPLE, BT., C.B., C.I.E., F.R.A. Chief Commissioner. Andaman and Nicobar Islands, from A.D. 1894 to 1903. (Continued from Vol. LII, page 224.) .

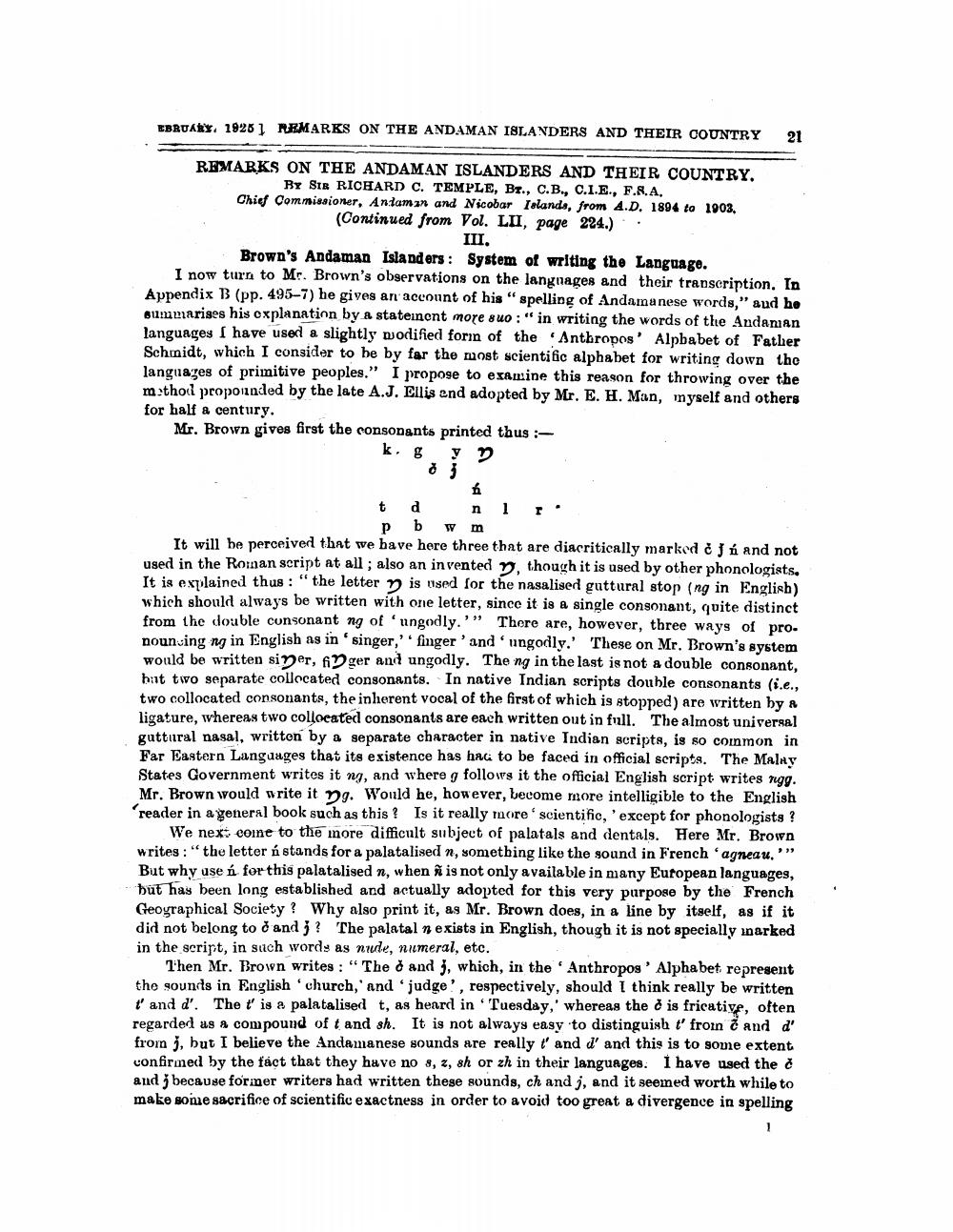

III. Brown's Andaman Islanders : System of writing the Language. I now turn to Mr. Brown's observations on the languages and their transcription. In Appendix B (pp. 495-7) he gives an account of his" spelling of Andamanese words," and he oummarises his oxplanation by a stateincnt more suo :" in writing the words of the Andaman languages I have used a slightly modified forn of the Anthropos' Alpbabet of Father Schrnidt, which I consider to be by far the most scientific alphabet for writing down the languages of primitive peoples." I propose to examine this reason for throwing over the method propounded by the late A.J. Ellis and adopted by Mr. E. H. Man, myself and others for half a century. Mr. Brown gives first the consonants printed thus

k. 8 y

pb wm It will be perceived that we have here three that are diacritically marked & J á and not used in the Roman script at all; also an invented . though it is used by other phonologists It is explained thus : "the letter 7 is used for the nasalised guttural stop (ng in English) which should always be written with one letter, since it is a single consonant, quite distinct from the double consonant ng of 'ungodly.'” There are, however, three ways of pro. nouncing ng in English as in 'singer,' finger ' and 'ungodly.' These on Mr. Brown's system would be written siner, finger and ungodly. The ng in the last is not a double consonant, hnt two separate collocated consonants. In native Indian scripts double consonants (i.e., two collocated consonants, the inherent vocal of the first of which is stopped) are written by a ligature, whereas two collocated consonants are each written out in full. The almost universal guttural nasal, written by a separate character in native Indian scripts, is so common in Far Eastern Languages that its existence has has to be faced in official scripts. The Malay States Government writes it ng, and where g follows it the official English script writes ngg. Mr. Brown would write it Dg. Would he, however, become more intelligible to the English reader in a general book such as this? Is it really toore' scientific, 'except for phonologists ?

We next coine to the inore difficult subject of palatals and dentals. Here Mr. Brown writes :"the letter ástands for a palatalised n, something like the sound in French 'agneau."" But why use á for this palatalised n, when i is not only available in many European languages, but has been long established and actually adopted for this very purpose by the French Geovraphical Society? Why also print it, as Mr. Brown does, in a line by itself, as if it did not belong to o and y? The palatal n exists in English, though it is not specially sparked in the script, in such words as nule, numeral, etc.

Then Mr. Brown writes: "The 7 and 3, which, in the Anthropog' Alphabet represent the sounds in English church,' and judge', respectively, should I think really be written tand d'. The t' is a palatalised t, as heard in 'Tuesday,' whereas the is fricative, often regarded as a compound of t and sh. It is not always easy to distinguish t' froin and d' from j, but I believe the Andamanese sounds are really t' and d' and this is to some extent confirmed by the fact that they have no 8, 2, sh or zh in their languages. I have used the and because former writers had written these sounds, ch and j, and it seemed worth while to make some sacrifice of scientific exactness in order to avoid too great a divergence in spelling