________________

SEPTEMBER, 1906.]

THE ORIGIN OF THE DEVANAGARI ALPHABET.

263

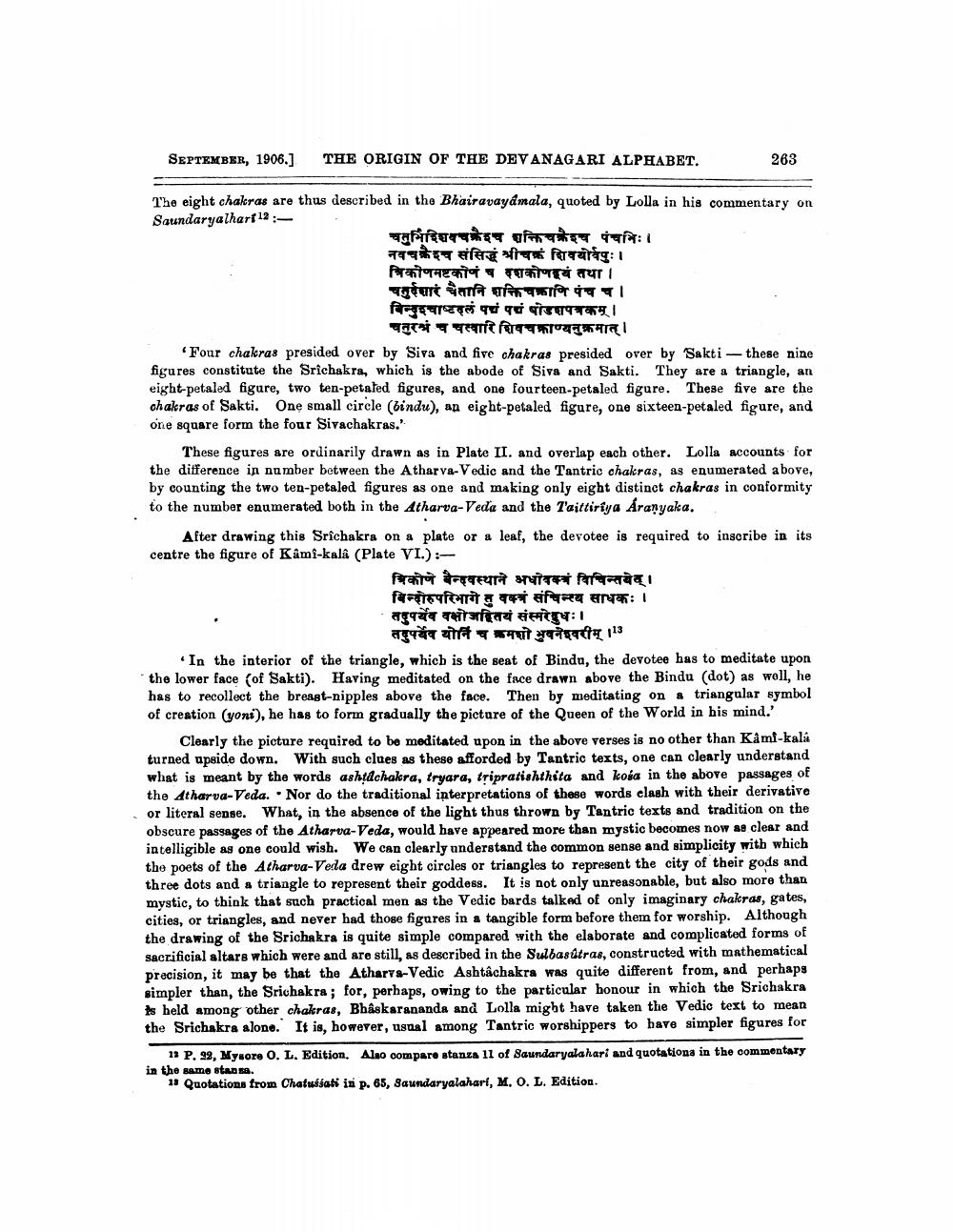

The eight chakras are thus described in the Bhairavayamala, quoted by Lolla in his commentary on Saundaryalharf 12 :

affure of

1:1 नवचइच संसिद्धं श्रीचक्रं शिवयोर्वपुः । त्रिकोणमष्टकोणं च दशकोणहवं तथा । चनुशारंचतानि शक्तिचक्राणि पंचच। बिन्नुइचाष्टदलं पर पचं षोडशपत्रकम् ।

चतुरनं च चत्वारि शिवचक्राण्यनुक्रमात् । Four chakras presided over by Siva and five chakras presided over by Sakti - these nine figures constitute the Srichakra, which is the abode of Siva and Sakti. They are a triangle, an eight-petaled figure, two ten-petałed figures, and one fourteen-petaled figure. These five are the chakras of Sakti. One small circle (bindu), an eight-petaled figure, one sixteen-petaled figure, and one square form the four Sivachakras."

These figures are ordinarily drawn as in Plate II. and overlap each other. Lolla accounts for the difference in number between the Atharva-Vedic and the Tantric chakras, as enumerated above, by counting the two ten-petaled figures as one and making only eight distinct chakras in conformity to the number enumerated both in the Atharva-Veda and the T'aittiriya Aranyaka.

After drawing this Srichakra on a plate or a leaf, the devotee is required to inscribe in its centre the figure of Kâmi-kalâ (Plate VI.):

त्रिकोणे बैन्दवस्थाने अधोवस्त्र विचिन्तयेत् ।

बिन्दोरुपरिभागेतु वक्त्रं संचिन्त्य साधकः । - तदुपर्येव वक्षोअहितयं संस्मरेवुधः।

तदुपर्वेव योनि च क्रमशो भुवनेश्वरीम् ।13 In the interior of the triangle, which is the seat of Bindu, the devotee has to meditate upon the lower face of Sakti). Having meditated on the face drawn above the Bindu (dot) as woll, he has to recollect the breast-nipples above the face. Then by meditating on a triangular symbol of creation (yoni), he has to form gradually the picture of the Queen of the World in his mind.'

Clearly the picture required to be meditated upon in the above verses is no other than Kamf-kalá turned upside down. With such clues as these afforded by Tantric texts, one can clearly understand what is meant by the words ashtdchakra, tryara, tripratishthita and kosa in the above passages of the Atharva-Veda. . Nor do the traditional interpretations of these words clash with their derivative or literal sense. What, in the absence of the light thus thrown by Tantric texts and tradition on the obscure passages of the Atharva-Veda, would have appeared more than mystic becomes now ae clear and intelligible as one could wish. We can clearly understand the common sense and simplicity with which the poets of the Atharva-Veda drew eight circles or triangles to represent the city of their gods and three dots and a triangle to represent their goddess. It is not only unreasonable, but also more than mystic, to think that such practical men as the Vedic bards talked of only imaginary chakras, gates, cities, or triangles, and never had those figures in a tangible form before them for worship. Although the drawing of the Srichakra is quite simple compared with the elaborate and complicated forms of sacrificial altars which were and are still, as described in the Sulbasitras, constructed with mathematical precision, it may be that the Atharvs-Vedic Ashtâchakra was quite different from, and perhaps simpler than, the Srichakra; for, perhaps, owing to the particular honour in which the Srichakra Is held among other chakras, Bhaskarananda and Lolla might have taken the Vedic text to mean the Srichakra alone. It is, however, usual among Tantric worshippers to have simpler figures for

11 P. 99, Mysore O. L. Edition. Also compare stanza 11 of Saundaryalahari and quotations in the commentary in the same stansa.

11 Quotations trom Chatušati isi p. 65, Saundaryalahari, M. O. L. Edition.