________________

SEPTEMBER, 1906.)

THE ORIGIN OF THE DEVANAGARI ALPHABET.

257

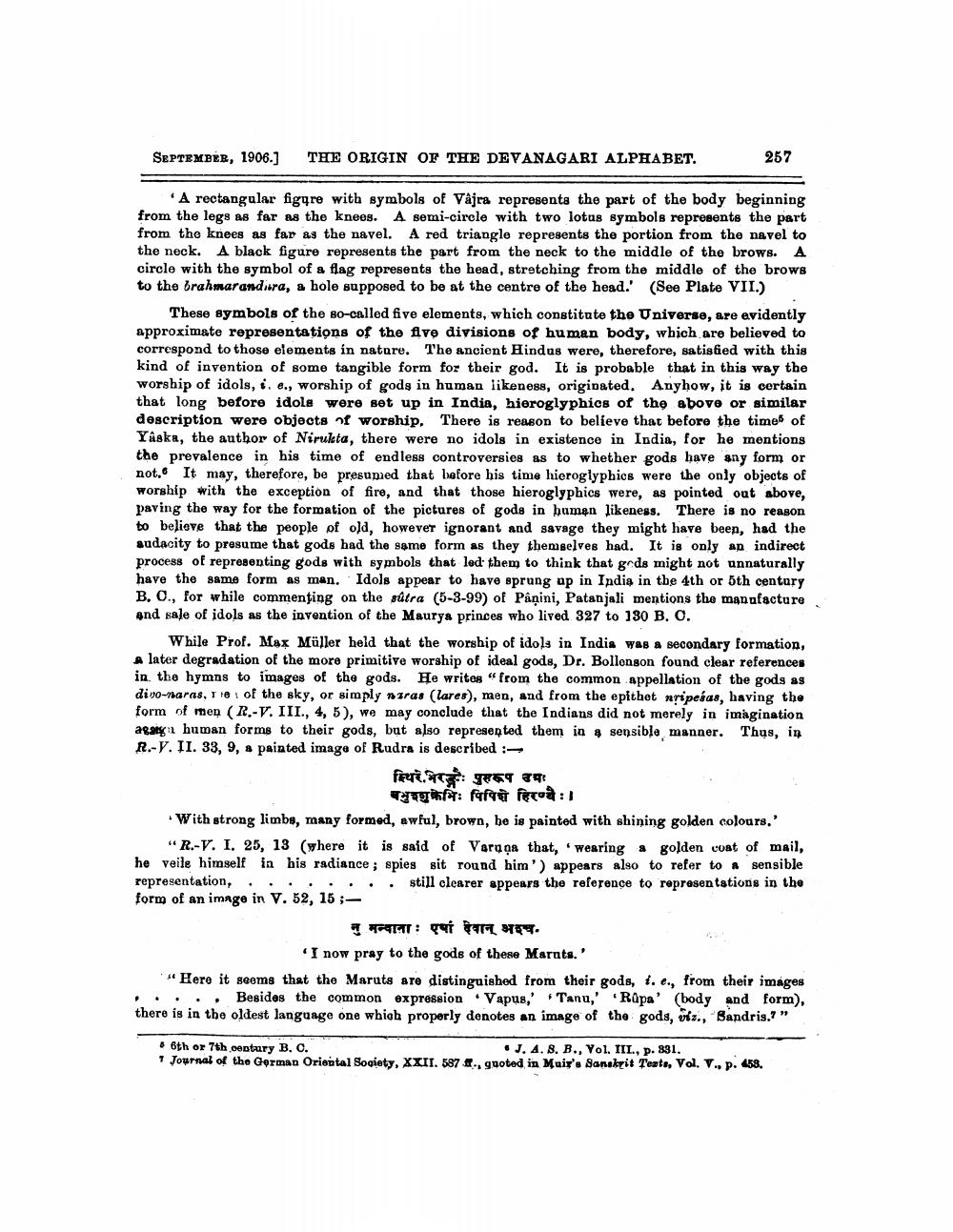

• A rectangular figure with symbols of Vajra represents the part of the body beginning from the legs as far as the knees. A semi-circle with two lotus symbols represents the part from the knees as far as the navel. A red triangle represents the portion from the navel to the neck. A black figure represents the part from the neck to the middle of the brows. A circle with the symbol of a flag represents the head, stretching from the middle of the brows to the brahmarandira, a hole supposed to be at the centre of the head.' (See Plate VII.)

These symbols of the so-called five elements, which constitute the Universe, are evidently approximate representations of the five divisions of human body, which are believed to correspond to those elements in nature. The ancient Hindus were, therefore, satisfied with this kind of invention of some tangible form for their god. It is probable that in this way the worship of idols, i. e., worship of gods in human likeness, originated. Anyhow, it is certain that long before idols were set up in India, hieroglyphics of the above or similar description were objects of worship. There is reason to believe that before the time of Yaska, the author of Nirulta, there were no idols in existence in India, for he mentions the prevalence in his time of endless controversies as to whether gods have any form or not. It may, therefore, be presumed that before his time hieroglyphics were the only objects of worship with the exception of fire, and that those hieroglyphics were, as pointed out above, paving the way for the formation of the pictures of gods in humen likeness. There is no reason to believe that the people of old, however ignorant and savage they might have been, had the audacity to presume that gods had the same form as they themselves had. It is only an indirect process of representing gods with symbols that led them to think that gods might not unnaturally have the same form as man. Idols appear to have sprung up in India in the 4th or 5th century B. O., for while commenting on the sútra (5-3-99) of Pâņini, Patanjali mentions the manufacture and sale of idols as the invention of the Maurya princes who lived 327 to 130 B. O.

While Prof. Max Müller held that the worship of idols in India was a secondary formation, A later degradation of the more primitive worship of ideal gods, Dr. Bollongon found clear references in the hymns to images of the gods. He writes" from the common appellation of the gods as divo-naras, Tie of the sky, or simply naras (lares), men, and from the epithet rripeáas, having the form of men (R.-V. III., 4, 5), we may conclude that the Indians did not merely in imagination agaya human forms to their gods, but also represented them in s sensible manner. Thus, in R.-Y. II. 33, 9, a painted image of Rudra is described :

feris 59 59

wagi: farge feroa: With strong limbs, many formed, awful, brown, be is painted with shining golden colours.'

"R-V. I. 25, 13 (where it is said of Varuna that, wearing a golden coat of mail, he veile himself in his radiance; spies sit round him ' appears also to refer to a sensible representation,........ still clearer appears the reference to representations in the form of an image in V. 52, 15;

नु मन्वाना: एषां देवान् अश्च.

I now pray to the gods of these Maruts. "Here it seems that the Maruts are distinguished from their gods, 1. e., from their images ..... Besides the common expression Vapus, Tanu,' Rupa' (body and form), there is in the oldest language one which properly denotes an image of the gods, viz., Bandris.?”

5 6th or 7th century B. C.

• J. A. 8. B., Yol. III, p. 831. Journal of the German Oriental Society, XXII. 587 ., guoted in Muix's Sanskrit Teata, Vol. V. p. 458.